“The world has been fed many lies about me..”

Richard Ramírez

Now available, the book: The Appeal of the Night Stalker: The Railroading of Richard Ramirez.

Welcome to our blog.

This analysis examines the life and trial of Richard Ramirez, also known as The Night Stalker. Our research draws upon a wide range of materials, including evidentiary documentation, eyewitness accounts, crime reports, federal court petitions, expert testimony, medical records, psychiatric evaluations, and other relevant sources as deemed appropriate.

For the first time, this case has been thoroughly deconstructed and re-examined. With authorised access to the Los Angeles case files, our team incorporated these findings to present a comprehensive overview of the case.

The Writ of Habeas Corpus

The literal meaning of habeas corpus is “you should have the body”—that is, the judge or court should (and must) have any person who is being detained brought forward so that the legality of that person’s detention can be assessed. In United States law, habeas corpus ad subjiciendum (the full name of what habeas corpus typically refers to) is also called “the Great Writ,” and it is not about a person’s guilt or innocence, but about whether custody of that person is lawful under the U.S. Constitution. Common grounds for relief under habeas corpus—”relief” in this case being a release from custody—include a conviction based on illegally obtained or falsified evidence; a denial of effective assistance of counsel; or a conviction by a jury that was improperly selected and impanelled.

All of those things can be seen within this writ.

The Writ of Habeas Corpus is not a given right, unlike review on direct appeal, it is not automatic.

What happened was a violation of constitutional rights, under the 5th, 6th, 8th and 14th Amendments.

Demonised, sexualised and monetised.

After all, we are all expendable for a cause.

- ATROCIOUS ATTORNEYS (4)

- “THIS TRIAL IS A JOKE!” (8)

- CONSTITUTIONAL VIOLATIONS (9)

- DEATH ROW (3)

- DEFENCE DISASTER (7)

- INFORMANTS (6)

- IT'S RELEVANT (17)

- LOOSE ENDS (15)

- ORANGE COUNTY (3)

- POOR EVIDENCE (16)

- RICHARD'S BACKGROUND (7)

- SNARK (12)

- THE BOOK (4)

- THE LOS ANGELES CRIMES (22)

- THE PSYCH REPORTS (14)

- THE SAN FRANCISCO CRIMES (5)

- Uncategorized (5)

-

You, the Jury

Questioning

The word “occult” comes from the Latin “occultus”. Ironically, the trial of an infamous occultist and Satanist is the epitome of the meaning of the word itself: clandestine, secret; hidden.

We’ve written many words; a story needed to be told, and we created this place to enable us to do just that.

Here, in this space, we intended to present the defence omitted at Richard Ramirez’s trial in violation of his constitutional rights. Our investigations have taken us down roads we’d rather not travel along, but as we did so, we realised that there was so much hidden we could search for a lifetime and still not see the end of it. Once we’d started, there was no turning back; we followed wherever it led.This was never about proving innocence; that was never the intent or purpose. We wanted to begin a dialogue, allowing this information to be freely discussed and for us to verbalise the rarely asked questions. We asked, and we’re still asking.

We can’t tell you, the reader, what to think; you must come to your own conclusions, as we did.

And so

We’ve said what we came here to say; with 114 articles and supporting documents, we’ve said as much as we can at this point.

This blog will stand as a record of that, and although we will still be here, we intend to only update if we find new information, if we suddenly remember something we haven’t previously covered, or to “tidy up” existing articles and examine any new claims (or expose outrageous lies) that come to light. The site will be maintained, and we’ll be around to answer any comments or questions.

What Next?

We will focus on the book being worked on; we’ve also been invited to participate in a podcast. When we have dates for those, we’ll update you.

The defence rests? Somehow, I sincerely doubt that; ultimately, we’re all “expendable for a cause”.

~ J, V and K ~

-

All The Broken Pieces

Multiple mental health professionals evaluated Richard Ramirez over several years, and they all came to the same conclusion: he was not mentally competent to stand trial in San Francisco. Based on this, the San Francisco District Attorney “stayed” the charges indefinitely – a fact quietly buried and never reported in the media.

The implications of this meant that Ramirez should never have stood trial in Los Angeles. The fault lies with Ramirez’s former attorneys, Arturo Hernandez and Daniel Hernandez and their failure to research his background before his Los Angeles trial. Had they done so, they would have found information detailing a history of seizures, abnormal EEGs, medical treatment, and a psychological evaluation.

It was clear to the original Los Angeles lawyers that something was wrong with Ramirez. Allen Adashek and Henry Hall both moved for competency hearings. As did attorney Joseph Gallegos. Manuel Barraza, who put Ramirez in contact with the Hernandezes also realised Ramirez had mental disorders.

Instead, Daniel Hernandez and Arturo Hernandez chose to turn a blind eye to his illnesses and covered them up – partly because of Ramirez’s paranoia and obstructiveness, but also for their own financial gain: they hoped to receive payment by way of book and movie deals for representing the case.

Mental Competency

Before we delve into Richard Ramirez’s mental health, I will briefly review the definition of mental competency within the confines of the judicial system. Mental Incompetency is not the same as a “not guilty by reason of insanity” plea.

Under the California Penal Code, for a defendant to be found incompetent to stand trial, the defendant must have a mental disorder that affects his ability to understand the duties of the officers of the court (judge and jury), understand the nature of the charges against him, the consequences of those charges and assist attorneys in the conduct of a defense in a rational manner. If a defendant does not meet the requirements mentioned above, per the law, they should be rendered incompetent to stand trial until they meet the standards set forth by the California Penal Code 1368.

Dr. Anne Evans’ Evaluation

Evans was a licensed psychologist who had conducted numerous forensic evaluations for criminal cases before she was sought by the San Francisco Public Defender’s Office to evaluate Richard Ramirez in 1991.

Between 1991-1995, she administered various psychological and personality tests to Ramirez. She reviewed declarations, police reports, newspaper articles, and medical, psychological, neuropsychological, educational, neurological, jail, prison, and trial records.

“The results of my psychological evaluation … indicate that Mr. Ramirez suffers from a serious mental disorder. The integration of all of my psychological test results in combination with prior assessment, history, records and consultation with current mental health evaluators reveals a strong consistency in the findings of longstanding mental impairment.”

– Dr. Anne Evans, Exhibit 73 of Richard Ramirez’s federal habeas corpus document 16.7.

She determined he suffered from disorganized, fragmented thinking, paranoid delusions, suspiciousness, and mistrust of others which significantly affected his ability to interact with his attorneys. He also had difficulty attending and concentrating. He suffered mood swings, depression, low self-esteem, and suicidal thoughts.

“In my profressional opinion, Mr. Ramirez has clearly not been able to assist his attorneys in the conduct of his defense in a rational manner and, therefore, meets the criteria of incompetence to stand trial pursuant to California Penal Code 1368. It is also my professional opinion, to a reasonable degree of psychological certainty, that this inability is the result of a mental disorder.“

– Dr. Anne Evans, Exhibit 73 of Richard Ramirez’s federal habeas corpus document 16.7.

Some criminal defendants may have depression, mood swings, and paranoia but are still competent to stand trial. Ramirez wasn’t just paranoid and delusional, he literally thought people were out to get him. He even thought his attorneys from the public defender’s office did not want him to “get off” and were colluding with the prosecution. This led to Ramirez being unable to rationally or reasonably assist with his defense or cooperate with attorneys.

He tried to prevent his attorneys from speaking to family, friends, and potential witnesses to gather medical and social history. Ramirez worked against his defense team and their efforts to save his life.

“To my knowledge, over the past ten years, every defense attorney who has attempted to work with this defendant to develop a defense strategy has encountered the same irrationality, paranoia and self-destructiveness. Investigators on the case in 1991 were frustrated by Mr. Ramirez’s refusal to discuss his childhood or reveal anything about his feelings and thoughts at the time of the offenses.”

– Dr. Anne Evans, Exhibit 73 of Richard Ramirez’s federal habeas corpus document 16.7.

Evans further elaborated on his delusions and self-sabotaging behavior:

“He was unable to appreciate the seriousness of the reality of dealing with 12 death sentences. On the other extreme, according to Mr. Martin [Randall, his attorney], Mr. Ramirez very much wanted to live, yet he did nothing to help in his defense and actively attempted to totally block access to his family. His paranoia caused him to be psychotically protective of his family to such an extreme that any attempts to discuss possible ways to save his life were out of the question if his family would be involved in any way.”

– Dr. Anne Evans, Exhibit 73 of Richard Ramirez’s federal habeas corpus document 16.7.

Although Ramirez attempted to block his San Francisco attorney’s efforts to mount a vigorous defense by not cooperating and helping them obtain information for a reasonable defense, they continued to work on his behalf despite the obstacles they encountered.

Randall Martin, one of the public defenders in San Francisco, went to El Paso, conducted interviews with family and friends, and obtained vital medical and social information. As a result of this, Martin was removed from Ramirez’s defense team because Richard was highly upset with him and no longer wanted him as his attorney.

However, the remaining attorneys, Daro Inouye and Dorothy Bischoff, continued working on Ramirez’s case and gathering the necessary information for his trial in San Francisco. Because of the diligent work of the San Francisco Public Defenders that represented Ramirez in the Pan case, the case never went to trial.

Anne Evans, like other professionals that evaluated Ramirez, believed he had a seizure disorder and that the it was the cause of the psychiatric illness symptoms he experienced. It’s reported in some books and online forums that there is no evidence Ramirez had seizures or treatment for such, and this is not the truth. Evans wrote as much here:

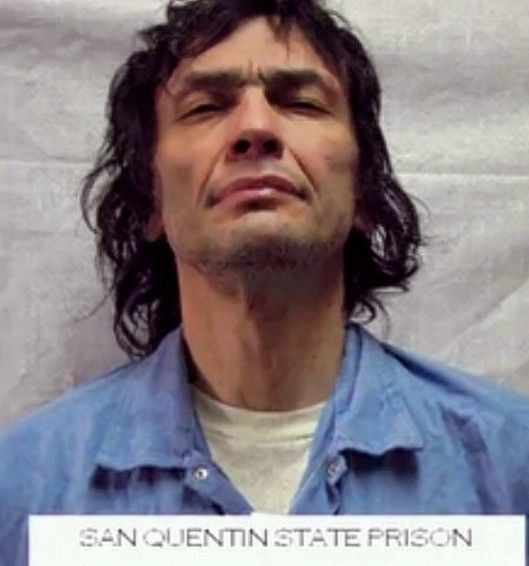

“Clearly, Mr. Ramirez’s mental problems have been of a longstanding and severe nature. Without intensive psychological treatment and appropriate medication – which I can safely say has not been provided for him either by the San Francisco County Jail or by San Quentin State Prison – the likelihood of any major changes occurring in Mr. Ramirez’s mental condition is essentially non-existent.”

– Dr. Anne Evans, Exhibit 73 of Richard Ramirez’s federal habeas corpus document 16.7.

Ramirez’s mental disorders were a direct result of temporal lobe epilepsy.

“There is strong evidence that Mr. Ramirez’s mental impairment is related to temporal lobe dysfunction. The constellation of symptoms and behaviors he exhibits are consistent with an organically-based syndrome of this type.“

– Dr. Anne Evans, Exhibit 73 of Richard Ramirez’s federal habeas corpus document 16.7.

While he was at the San Francisco County Jail and at San Quentin Prison, multiple physicians and psychologists determined that Ramirez suffered from a thought and mood disorder, specifically psychosis (delusions/disorganized thought patterns) and depression. These can be treated and cured with appropriate medication.

Ramirez was a sick young man urgently needing treatment for his mental health conditions. He was not “crazy” – he was suffering from serious but treatable mental health conditions. Instead, he was locked up and sentenced to death. Is justice served by sentencing a seriously mentally ill young man to death? If that’s what we believe, we may need to reassess our definition of justice.

Psychosis is a disorder characterized by delusions, hallucinations and/or disorganized thought patterns. Psychosis is not a personality disorder. It is not anti-social behavior such as psychopathy or sociopathy. Psychosis can and does occur in individuals with a history of temporal lobe epilepsy and is treatable

– Kaplan & Sadocks Concise Textbook of Clinical Psychiatry, 5th edition, 2023).Kaycee

-

First Touch – The Vicary Report, September 1985

*Some images may be better viewed on a desktop because of the size*

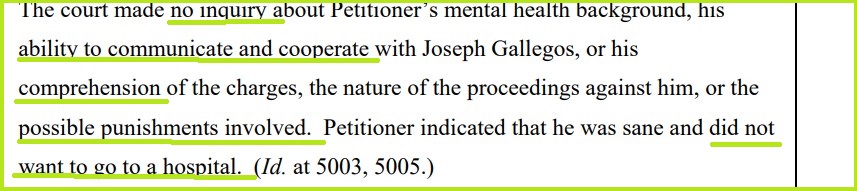

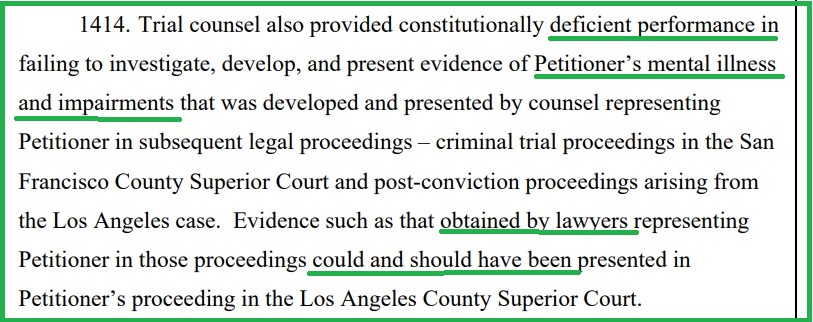

“The trial court failed properly to inquire about and conduct a full

Writ of Habeas Corpus page 191

hearing as to Petitioner’s mental competency to actively participate in the proceedings. Petitioner was entitled to a full and fair determination of his mental competency in this multiple murder capital case”.

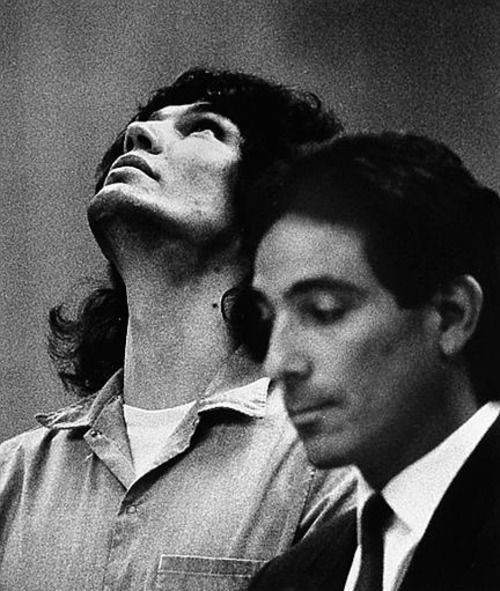

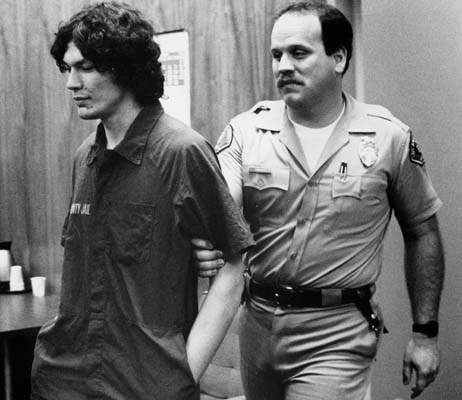

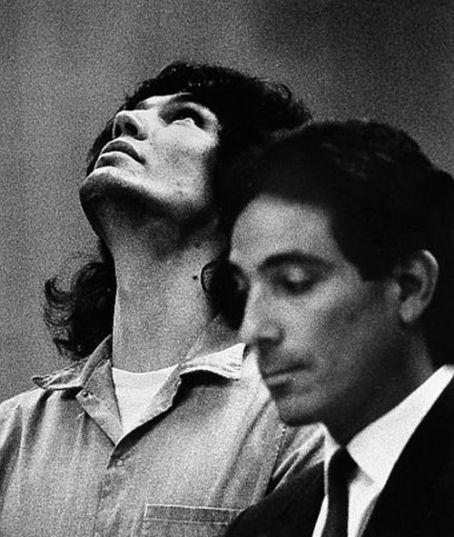

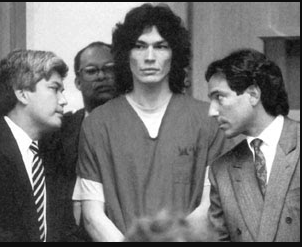

Richard with attorney Daniel Hernandez from the Herald Examiner Collection. Photo dated 8th May 1989, credit: Mike Sergieff.

Penal Code § 1368

The Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution protects the requirement that a defendant be mentally competent to stand trial.

Under California law, a defendant’s mental competency to stand trial is defined in Penal Code § 1368 PC. Under this section, if a judge believes that a defendant lacks the cognitive ability to understand the legal proceedings and assist in their defence, then the judge must state that belief in the court’s record. In such cases, a hearing may be ordered to assess if the defendant is incompetent.

This code section requires the judge presiding over a criminal case to do two things if they believe a defendant is mentally incompetent.

- State their doubts about the defendant’s mental competency in the official court record.

- Ask the defendant’s attorney for their opinion of the accused’s competence.

The presiding judge should order a competency hearing if the defence can show substantial evidence of incompetency. The purpose is to establish whether the accused is fit to stand trial.

Mental Competence in Law

A defendant is incompetent to stand trial when they suffer a mental disorder or developmental disability rendering them unable to:

- Understand the nature of the criminal proceedings, or

- Assist counsel in the conduct of a defence in a rational manner.

A development disability is a disability that:

- Begins before a person is 18 years old, and

- Continues, or is expected to continue, for an indefinite period. (Source: Shouse California Law Group)

In the case of Richard Ramirez, both of these situations applied. Forgive the “legalese” once more, but it is essential to understand the context of penal code 1368 when reading the post (I kept it concise).

Writ of Habeas Corpus page 184

When you Google the “Night Stalker” crimes, you’ll find a lot of info about the crimes, his childhood and a thousand edits. His mental health evaluations detailing the various psychological tests and corresponding results are missing. There is a reason for this, much of which has been covered in this post and again here and here. (I invite you to read them for an overview of the trial and to gain an understanding of what was done). However, there are records concerning this subject going back to the 1970s.

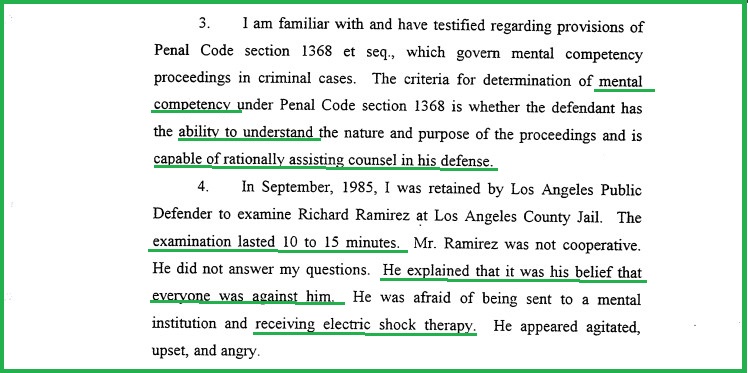

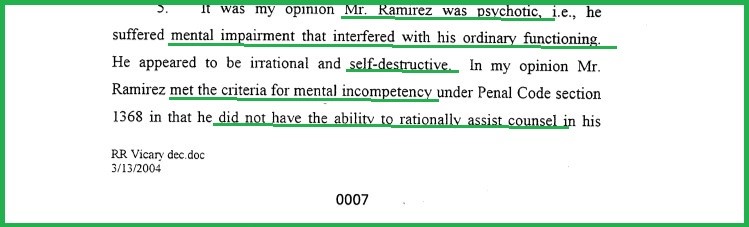

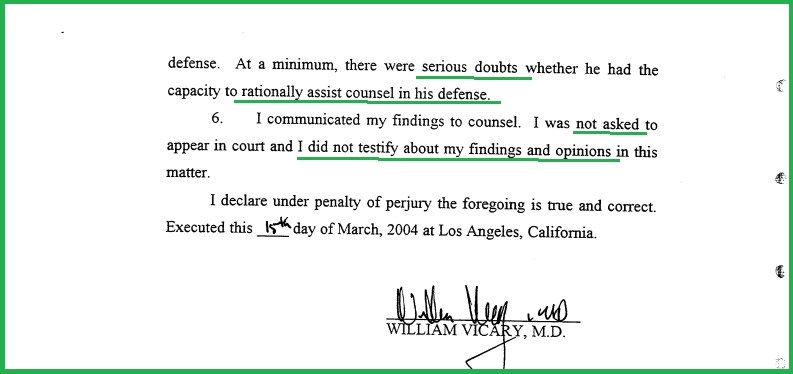

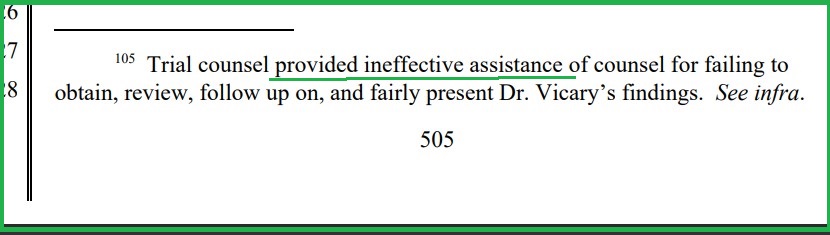

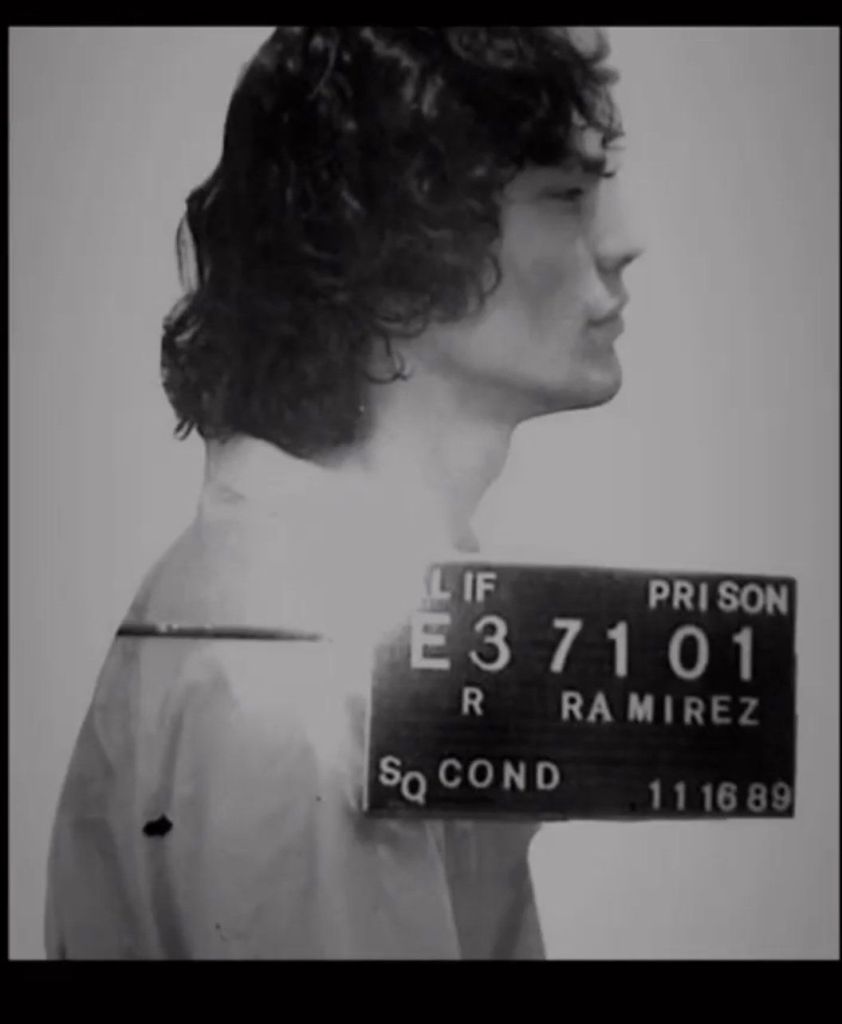

Declaration of William Vicary, doc 7-21. Doubts raised in Municipal Court

On October 24th 1985, before he was replaced by Daniel and Arturo Hernandez, Joseph Gallegos, briefly retained by Richard as his defence attorney, informed the court that he had grave concerns about his mental condition and moved to suspend criminal proceedings. In early September, just after the arrest of Ramirez, public defender Henry Hall (Richard’s first assigned counsel) had the same concerns over competency and had arranged for a psychiatrist, William Vicary M.D, to examine him at Los Angeles County Jail. Vicary was the first in a long line of psychiatrists who would come to examine him before and after his LA convictions.

Possibly because he was mentally unwell? From The LA Times, September 1985. One might speculate this is when they decided he needed a psychiatric evaluation.

LA Times, September 1985. Why was he shrieking during his arraignment? No one was answering that.

LA Times, September 1985.

Declaration of William Vicary M.D, doc 7-21. An examination that lasted 10 to 15 minutes.

Before ruling on the competency motion tabled by Joseph Gallegos, the trial court asked Hall about the confidential psychiatric evaluation. Hall reported that Richard had been uncooperative, refusing to answer questions, expressing his fear that “everyone was out to get him”, and fears that he would be subjected to electric shock treatment.

Gallegos renewed his request that Richard should have a full and proper psychiatric examination per Penal Code § 1368. The court, however, found that he wasn’t mentally incompetent under § 1368 because he “remembered things”. Because he remembered things. What things? His name? His date of birth? What he had for breakfast? They made the decision even though, after spending such a short time with him, Vicary could determine that things were wrong with Richard Ramirez.

Richard did not want to be regarded as insane and commented, “I don’t want to go to no hospital, Ma’am”.

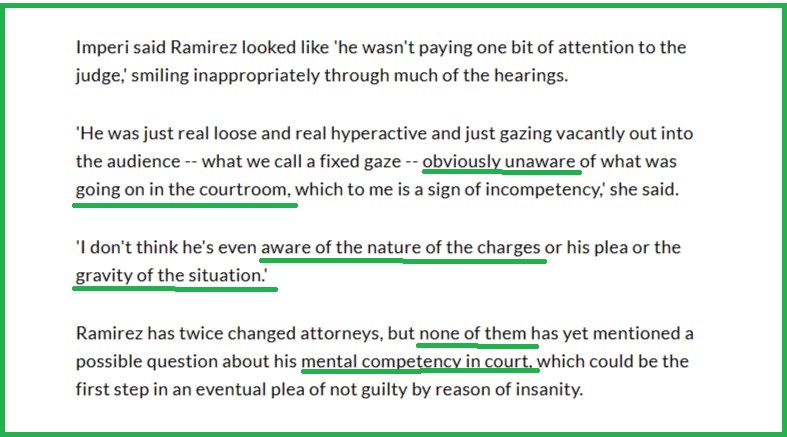

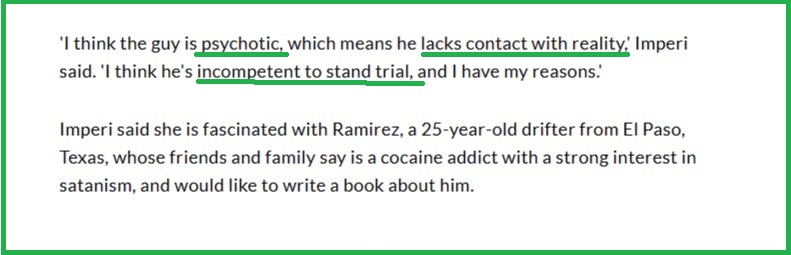

On observing him in court during October 1985, a Los Angeles psychiatrist revealed her thoughts to a newspaper; the article is from the UPI Archive and is dated 28th October 1985, four days after Joseph Gallegos raised his concerns over Richard’s mental state. That wasn’t public knowledge, for she says none of his lawyers attempted to highlight the issues. As we’ve seen, that wasn’t true; she doesn’t know as she wasn’t party to that information because she wasn’t attached to the case; she was watching from the gallery. Gallegos tried, as did Henry Hall; Arturo and Daniel Hernandez did not. The trial court wasn’t listening. If a court observer could see the problem, it is reasonable to assume that the trial court was aware but chose to ignore it. In the news article, Ramirez is called the Night Stalker, another example of media bias. This was in 1985; he wasn’t convicted until 1989.

From the UPI Archive, the thoughts of Dr Lillian Imperi, a psychiatrist with over 30 years clinical experience. Swipe through the gallery above.

Declaration of William Vicary.

What Happened to the Reporter’s Transcript?

Subsequently, an in-camera hearing was held on April 14th, 1986. However, despite repeated, diligent efforts of state appellate counsel to obtain a complete record on appeal, the sealed reporter’s transcript of the hearing held that date was not made part of the record on appeal, and no settled statement summarising that hearing could be obtained.

An” in camera” hearing means privately, in chambers, and out of the public eye. Richard’s appeal lawyers could not recover whatever was said within that room; the transcript was sealed. Richard was absent from this discussion.

His lawyers at this time were Daniel and Arturo Hernandez, who were both fully aware of the findings of Vicary and Dietrich Blumer, M.D, neuropsychiatrist (whose report will be discussed in a future post). The Hernandez’ did not follow up on the accounts of either.

William Vicary from his declaration in doc 7-21. He was not asked to testify at the trial. There was no determination of Richard’s mental competency in the Municipal Court.

The subject of Richard’s mental impairment has been brushed aside over many years, and it was only because his San Francisco attorneys arranged for him to be correctly assessed that it is possible to understand the depth of his condition. The public defenders in San Francisco did their work thoroughly; we can hardly say the same for LA.

“Competent counsel could and should have investigated, developed, and presented evidence that Petitioner, from his childhood and continuing to the present day, suffered from long-standing and severe psychiatric, psychological, neurological, and cognitive impairments, including, but not limited to, long-standing temporal lobe epilepsy; mental incompetency in September 1985; thought disorder of psychotic proportion, resulting from his seizure disorder; psychotic disorder; disorganized speech, thought, and behaviour; hallucinations, delusions, paranoia; severe mood disorder; brain damage; severe impairments in memory tasks and higher cognitive functioning, of a kind typically associated with impairment of the frontal and temporal lobes; impairments in his ability to inhibit behaviour and responses and obsessive and compulsive behaviours; and the impact on his behaviour and personality of multiple disorders – all of which established that Petitioner was seriously mentally ill and incompetent to stand trial and waive his rights and which would have constituted effective defences, at guilt and penalty, to the crimes charged against him.”

Writ of Habeas Corpus page 512

Please note: psychosis is a severe mental disorder in which thoughts and emotions are so impaired that contact with external reality is lost. It is not psychopathy; Richard was never diagnosed with psychopathy.

Writ of Habeas Corpus page 507 Because Petitioner was incompetent to stand trial, based upon this

Writ of Habeas Corpus page 174

social history and mental health evidence developed by lawyers at the SFPD, his criminal trial proceedings in the San Francisco County Superior Court were stayed indefinitely in 1995 and were never brought to trial. For the same reasons, he was incompetent to stand trial and waive rights in the Los Angeles proceedings.If Richard was found incompetent in San Francisco, he would be similarly incapable in Los Angeles. Rather than come out and say this, for to do so could compromise the LA convictions, the trial in San Francisco was simply stayed instead.

The Poor Outsider

The public defender Henry Hall, and after him (briefly) retained counsel Joseph Gallegos, had tried to intervene, but Richard replaced them with underqualified attorneys. A decision that could have and should have been overruled by the court, especially when the accused was not competent to understand how badly he was being represented and what was required from his defence counsel.From the beginning, it is painfully clear that Richard was let down by those who had a duty to defend him and protect his constitutional right to a fair trial. The odds were always stacked against him. The poor “outsider”, the “misfit”, had fallen through the cracks, and no one was picking up the pieces or seemingly helping him, as he could not help himself. The errors are many, from deficient lawyers to false evidence presented and a jury misled. One of the saddest realisations is the cover-up of his mental health during a conflict of interest that was out of his control and beyond his capability or understanding to correct. He was, after all, a person who believed that being checked out in a hospital equalled electric shock therapy.

As we have often said, the central theme here is a trial that was neither fair nor constitutionally correct; it is not about guilt or innocence but rather the lack of a solid and vigorous defence, which every accused person should have, no matter who it is. The issues surrounding the mental health of Richard Ramirez should have been drawn upon in both the guilt and penalty phases, and especially in mitigation. They were not.

“Nothing can make injustice just but mercy.” – Robert Frost.

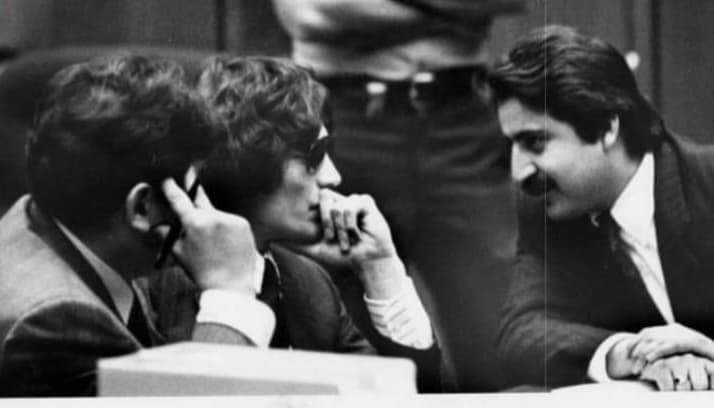

Richard with post conviction attorney Randall Martin; San Francisco. ~ Jay ~

-

A Bad Seed

So much of what we think we know about Richard Ramirez is based on myths and rumors. It’s like the “telephone” game played in the United States. Someone makes a statement, and that statement becomes so distorted that it doesn’t even remotely resemble what was said to begin with. The story gets changed and no longer has an element of truth in it. Is it so hard to believe that this is the case with Richard? Is it difficult to believe that most, if not everything, you have read and heard about him couldn’t possibly be true or may only represent a small part of his ever-changing story?

The few interviews he gave during his lifetime have been taken out of context, twisted, turned and made into something sinister. They have been made out to mean something that they didn’t. There are some that continue to perpetuate the rumors and untruths with absolutely no evidence to back up their claims or statements. And the story keeps growing and changing so much so that none of us know who Richard Ramirez really was.

Richard Ramirez wasn’t born a “bad seed.” He wasn’t a “bad kid”. Yes, he had some struggles. Had anyone of us walked in his shoes likely we would have experienced unfortunate events as well. For those that think he was evil incarnate from the moment he arrived on the planet, and for those who don’t, let’s look beyond the rumors and the myths and look at the evidence that exists.

In a previous post, we discussed how Richard was not a troublemaker as a child and how he did well in school, at least until the onset of the seizure disorder he developed at the age of 12-13. It was only after this that he began to misbehave and use drugs. And even then, those misbehaviors were relatively mild.

Richard’s first contact with the criminal justice system was in 1974, at the age of 14, for criminal mischief. He attempted to steal something, the record does not indicate what it was, but he was merely issued a warning. So, whatever it was didn’t warrant a proper arrest so we can conclude it must have been negligible. For the next two years there is nothing in Richard’s juvenile record indicating any criminal behavior.

In May of 1976, Richard was charged with committing theft that was “over $20 but less than $200” (no specifics were given as to what was stolen). He was released to his parents and the case was closed without any further investigation.

The following month, Richard was apprehended for burglary of a residence. Again, no specifics are given as to what was stolen. The case was dismissed by the county prosecutor because whoever filed the complaint couldn’t be located. In July of 1976, Richard was given a warning for disorderly conduct.

Two months later, in September, Richard was accused of burglarizing a residence but this case was also dropped due to lack of a statement from the person seeking prosecution.

The following month Richard was given a warning by the El Paso police for vandalizing U.S. postal property. December 16, 1976, Richard was accused of burglarizing a home. The individual that pressed charges waited 12 days before doing so and no specifics were given as to what, if anything, had been stolen from the property. It was this last incident that Richard ended up going to court for in March of 1977. Richard was never on probation or arrested for any of the aforementioned incidents. Not even the one that occurred in December 1976.

Philip Carlo’s Unverifiable Claims

In Philip Carlo’s book The Life and Crimes of Richard Ramirez, Carlo tells the story of Richard working for a hotel as a teenager. Carlo states Richard was in an elevator one day while at work when two teenage girls got on the elevator. Richard politely told one of them she was pretty. The young lady adid not appreciate what Richard said and she reported it to her parents who notified hotel management. Ramirez was reprimanded by the manager.

Somehow this story has morphed into Richard sexually assaulting these teens girls. However, Richard’s juvenile record does not list any such occurrence. Had Richard assaulted the teen girls he met in the hotel elevator, it would have been listed along with the other crimes he was accused in his criminal record. I would like to point out that in the hundreds of pages of documents submitted with the 2008 federal petition, there is absolutely nothing indicating Richard ever sexually assaulted anyone when he was a minor.

Contrary to popular opinion, Richard Ramirez was polite to girls and not violent towards them. The following comes from his school friend Ana “Patricia” Kassfy who wrote a character witness statement in 2004. It was used for both his 2006 direct appeal and his 2008 federal habeas corpus petition:

“Richard was a joker and when I was with him, we always laughed. Freshman year, he and I walked to school together practically every day. Richard stopped coming to school that year. In the ninth grade, I went home for lunch almost every school day.

Even when he was no longer attending school, Richard waited for me at the corner almost every school day and walked me back to school after lunch.

There were two ways to get to school. The shorter way was ten minutes faster, but you had to walk through three blocks of a really bad neighborhood. There was a lot of drug use … and the kids … frequently beat up other kids. On the days that Richard walked me back … we ran those three blocks in order not to be beaten up and harassed.”– Patricia Kassfy, exhibit 123, Document 20.8

Richard himself stated that anyone reading Carlos book should “take it with a grain of salt.” Carlo used creative license when writing it as his goal was to sell a book and Richard stated there were many untruths in it.

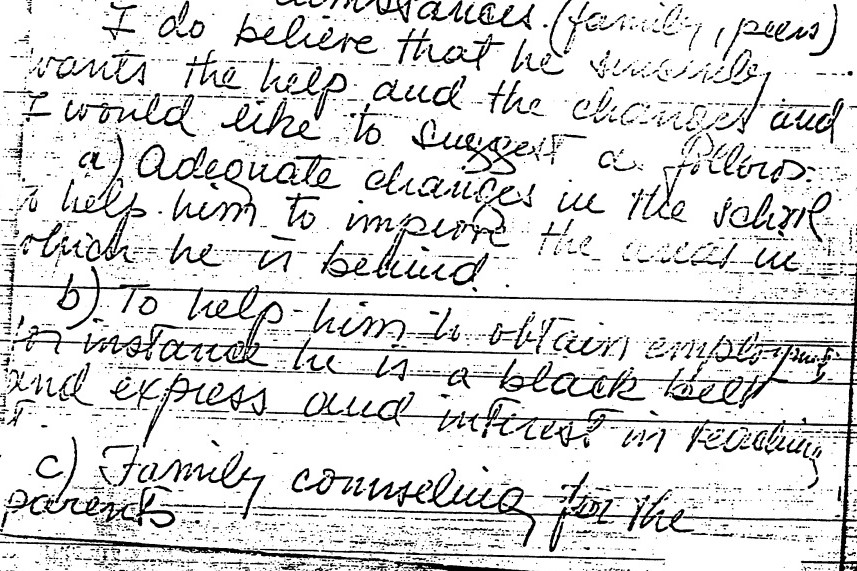

The El Paso Child Guidance Center

Richard was seen at the El Paso Child Guidance center three times in 1976. A psychological evaluation and personality testing were completed by Dr. Ursula Niziol who concluded Richard was depressed, withdrawn and had suicidal ideations. He did not have a personality disorder nor was he homicidal. The counselor who saw Richard at the guidance center determined he wanted help with getting back on track with school, finding employment and staying off drugs. She even stated Richard was a “black belt” in Karate and expressed an interest in teaching it.

The El Paso Child Guidance Center recommended individual counseling for Richard and family counseling for him and his parents. From the information that is available to us, it does not appear this happened. Clearly, Richard needed help at this point in his life because he was struggling with depression, suicidal thoughts, using drugs, getting in trouble for not going to school, and had several encounters with law enforcement.

No one is pointing the finger at anyone, but instead of getting counseling and help finding employment and with school, Richard fell through the cracks and was merely left to his own devices and thus, he ended up in court a few months later, followed by a stint in reform school with Texas Youth Council (TYC).

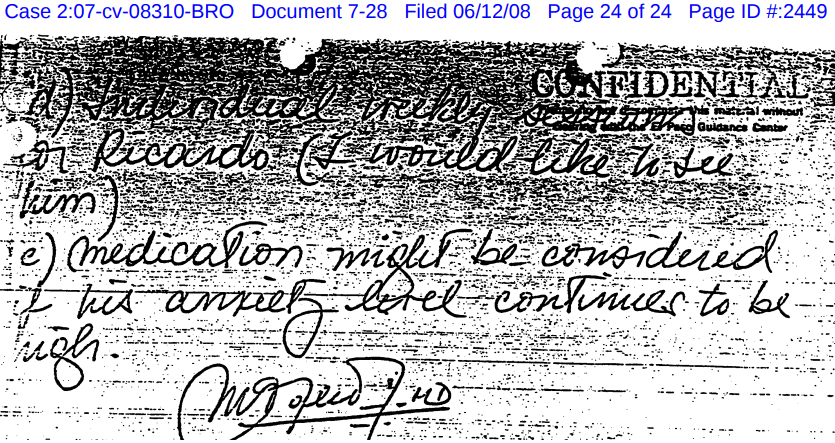

Below is a 1976 evaluation from a counsellor:

“I do believe that he seriously wants the help and the changes and would like to suggest as follows;

a) Adequste changes in the school to help him to improve the areas in which he is behind.

b) to help him to obtain employment – for instance he is a black belt and expresses an interest in teaching it.

c) Family counselling for the parents.

d) Individual counselling sessions for Ricardo. I would like to see him.

e) Medication might be considered if his anxiety continues to be high.”

Images of the 1976 evaluation

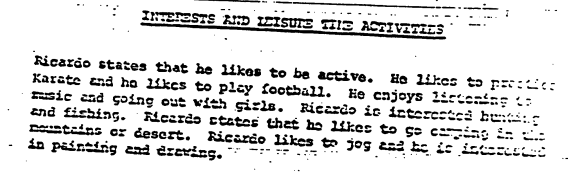

Richard was also an active youth with hobbies. He was once a boy with a lot of potential:

“Ricardo states that he likes to be active. He likes to practice Karate and he likes to play football. He enjoys listening to music and going out with girls. Ricardo is interested in hunting and fishing. Ricardo states that he likes to go camping in the mountains or desert. Ricardo likes to jog and he is interesting in painting and drawing.”

– Statement from the psychological evaluation completed by Dr. Niziol at the El Paso Guidance Center in 1976

Let me reiterate the findings of the psychological evaluation. The alleged big bad Night Stalker was not diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder in his youth as Philip Carlo implies (he does not directly state these diagnoses). This means he was not a budding sociopath or a psychopath. He was depressed and anxious, at times.

Alleged Cruelty

Furthermore, there is nothing in any of the psychological evaluations stating Richard was cruel to animals or a sexual deviant with predatory behaviors. We discovered claims to to the contrary that it wasn’t Richard, but his brother, Robert who was cruel to animals, setting cats on fire.

“Robert was very strange. Four times I saw him set fire to cats in a tunnel underneath the I-10 freeway near Ledo Street [where the Ramirez family lived]. Richard was different from the rest of the kids in our neighborhood. He was timid and the other neighborhood kids gave him a hard time.”

– David Palacios, Ramirez’s childhood friend, exhibit 126, document 20.5.

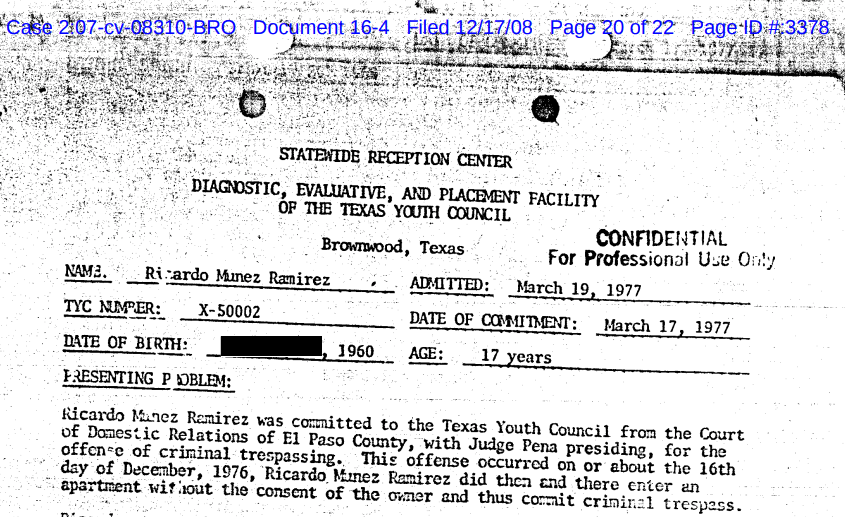

Texas Youth Council

In March 16, 1977, Richard appeared before a judge to answer for the burglary charge from December 1976. By this point the charge had been changed from burglary to criminal trespassing. No reason is given for the change in the charge.

Richard was found guilty because of an alleged eyewitness identification. Back in December of 1976, a police officer came to Richard’s home and told him of the accusation against him. The officer told Richard the person that was accusing him of burglary wanted to see him so that he/she could determine if Richard was the one who trespassed on their property. The officer basically told Richard if he had nothing to hide then he shouldn’t be concerned about letting this individual have a look at him. So Richard naively and willingly went with the police officer to the home of the accuser.

The police officer told Richard he needed to get out of the police car and stand beside it, so he did. It was then that the accuser looked out of a window to get a look at Richard. Based on this glimpse from the window, the accuser said Richard was indeed the person who trespassed on their property. That was used as evidence against him. Quite obviously this is not a legitimate way of identifying a perpetrator so why it was admissible in court, we don’t know.

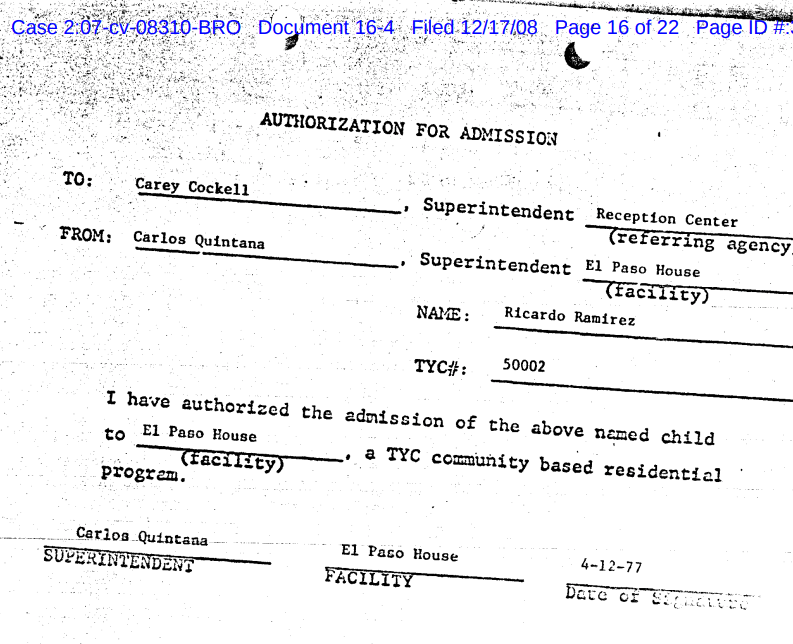

The judge determined Richard should be sent to “reform” school for the criminal trespassing charge. So, on March 17, 1977, Richard was sent to the Texas Youth Council statewide reception center in Brownwood, Texas, to begin the process of placing him in the reform school system.

The Statewide Reception Center determined Richard was “suitable for community placement,” indicating he wasn’t violent, he wasn’t a sexual predator, and did not need to be separated from other juveniles in the reform school system. Staff stated he “responded to supervision very well” and that he enjoyed group activities with peers. Richard was placed at the “El Paso House,” a juvenile group home.

His estimated length of stay was approximately five months with the goal of family reunification after he was discharged. Reports indicating exactly how long Richard stayed in reform school have not been located but it may have been until his 18th birthday or close to that time, as an individual could not be kept in a youth reform system past the age of 18.

The purpose of reform schools that existed in the 1970’s in the United States was rehabilitation. We don’t know much about what happened during the time Richard spent at El Paso House. His records from the time he spent there may be unavailable because he was a juvenile or the records may be amongst the thousands of documents submitted along with his 2008 federal writ of habeas corpus petition but are sealed for some reason, so we don’t have access to them.

We can speculate on what may or may not have happened during his time with the Texas Youth Council based on his behavior after he was released. What should have happened while Richard was at TYC is he should have earned his general education diploma, received vocational training, and counseling and treatment for depression and drug abuse.

Richard’s death certificate indicates he was a high school graduate so likely he did get his general education diploma while at TYC. But it doesn’t appear he received any type of vocational training nor any treatment for depression or drug abuse.

So, what happened to the rehabilitation purpose the Texas Youth Council was supposed to serve for Richard? Did this reform school fulfill its purpose? Did it help Richard with gainful employment? Did it give him the skills to stay out of trouble and not use drugs? The answer would be no on all accounts. If the system ever failed anyone, it was Richard Ramirez.

So many opportunities existed to change the course of his life. While it’s true we can’t make anyone do something they don’t want to do, per the counselor’s statements Richard wanted help. It was known he suffered from depression and needed treatment. It was also known he suffered from a seizure disorder, yet no treatment or follow-up care was provided for that either.

We should be asking ourselves “why not?” Why didn’t he receive vocational training? Why didn’t he get counseling and medical treatment during the time he was at El Paso House? He was under the complete control of the reform school system. He had been court ordered there. He could have just as easily been ordered to receive counseling and treatment. During the time he was at the El Paso House he would not have had access to drugs or have been able to burglarize either. This was the perfect opportunity for rehabilitation. So why did the system not provide Richard with the tools and skills he needed to be rehabilitated? Why was he not provided with medical care and treatment when it was apparent he needed it?

Further reading:

-

The Monster in Fetters

Richard Ramirez’s constitutional rights were violated on multiple occasions because he had waived his rights, due to being mentally incompetent and unable to understand what was happening – not because he was simple, but because his thoughts were disordered due to temporal lobe disorder.

Ramirez’s Habeas Corpus lawyers made 43 separate claims of a ‘Miscarriage of Justice.’ Claim 22 relates to the fact that Richard was unconstitutionally shackled throughout his capital trial and due to his inability to understand his rights, he agreed to being treated this way. But his agreement does not make it right – if his mental health assessments had not been suppressed or ignored, he would not have been given such a choice.

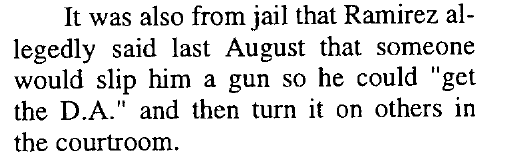

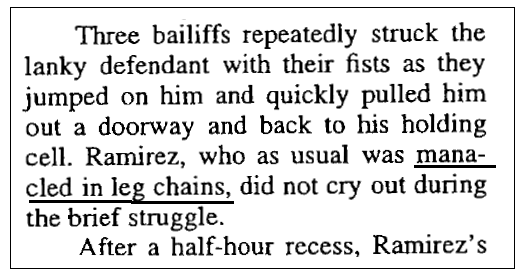

The unconstitutional use of restraints is not exclusive to the Ramirez case – this violation happens often, but for his trial in particular, the courts manufactured excuses for his leg chains, namely preposterous claims that Richard was somehow plotting to escape during the trial and kill the District Attorney, a fantasy that has probably crossed the mind of many a prisoner, but there was no proof he really said this and it is one in a long list of “confessions” that police failed to record.

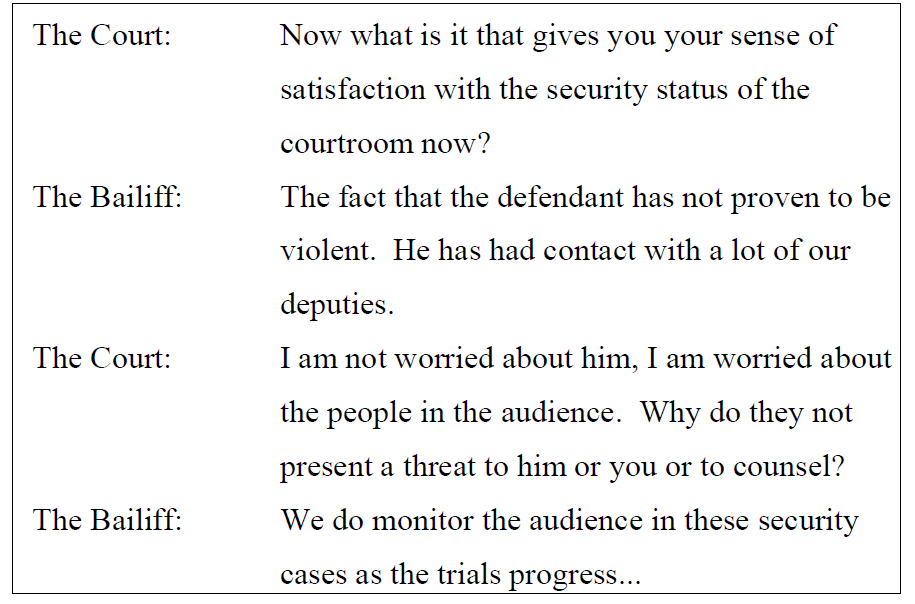

The issue of Ramirez’s restraints had been ongoing since the 1986 Preliminary Hearing. While Richard was not present, the court changed its mind on what kind of shackles he should be wearing. Richard was originally required to wear only handcuffs, but they decided he must wear the ankle shackles instead. This decision was made because a marshal claimed that Richard had told him he wanted to escape (what prisoner doesn’t want to escape?), and planned to do so by attempting to steal the officer’s weapon. The court stated as follows:

“Based upon that, we have elected to proceed in this fashion. I am not welded (sic) to it. If things go well, we may change. It is also better for your client’s benefit to have a rather peaceful Marshal’s Corp.”

Federal Writ of Habeas Corpus pg. 577Later, still in 1986, there was another discussion between all involved parties (again without Richard), regarding security in the courtroom. Richard’s trial counsel was worried as they had received death threats (when the public is so hyped up against a defendant, they stop believing in natural justice, apparently), so the court brought in a law enforcement ‘sergeant’ to discuss security. The court metal detector had failed, which required hand searching, but they decided not to conduct searches, nor did they bother to replace the metal detector. For such a high-profile case, minimal effort was being made.

The next part of the discussion involved Richard’s level of threat.

On 19th December 1988, facing jurors for the first time for the jury selection process, Ramirez was visibly restrained and yet another discussion took place on whether he should be wearing a leg brace or ankle chains. Halpin, who went on to prosecute Ramirez, pointed out that the defendant was wearing them and should not be – there was a legal precedent against it. He felt that they needed to address the issue once more, because the chains would be visible as the jurors entered past the counsel table.

Richard’s attorneys suggested that his restraints should be removed entirely. Halpin disagreed and suggested a leg brace, as it was less visible. However, Richard found the leg brace to be painful and the court accepted that the defendant should not be “uncomfortable and physically in pain” during the trial. However, because of some alleged threats, the court declared that Richard was too much of risk – the shackles must remain.

The court acknowledged that the restraints had been visible to the prospective jurors, so the defence attorneys suggested a solution – to place a curtain or barrier in front of the table so the chains would not be visible. The request seems to have been ignored – the court did not care about the defendant’s constitutional rights. Yet again, at a January 1989 hearing, Ramirez was visibly chained in front of the jury, and the court offered him the painful leg brace once more. Richard stated that he did not wish to wear any restraint but was told the sheriff feels they are necessary – no doubt because of baseless claims that Ramirez had made a threat.

The court took a ‘waiver’ – a supposed “willingness” from Richard to wear the shackles, despite his statement that he did not wish to. The Petition states this waiver was not valid – Richard was not advised of his constitutional right to refuse beforehand and so he proceeded in chains.

The visibility of restraints – or even prison attire – infers guilt on a psychological level. To see someone in shackles gives the impression of a wild and dangerous animal and encourages fear.

The court instructed the jury to ignore Richard’s shackles.

“You may have observed that the defendant has worn restraints while in the courtroom. This fact shall have no bearing upon your determination of the defendant’s guilt or innocence. That determination must be based solely upon the evidence presented to you.”

It was not good enough. Several of the jurors mentioned seeing them and had been led to believe that he was a danger to the court – on top of the crimes he was charged with. The following images are from their witness statements for his Habeas Corpus appeal. This is what they said, from Document 20-8.

From Max De Reiter.

From Bonita Smith

From Janice McDowell (alternative juror) Journalists in the press gallery also noticed and remarked upon them at all stages of the trial. From the Los Angeles Times, 1st May 1986, 21st September 1989 and 25th September 1989, from Documents 19-8 and 19-9.

It should be noted that, while far from a model citizen, Richard Ramirez had no history of violence before, or after the alleged crimes. This includes the time he was in the custody of the Texas Youth Council, and up until the point of the trial. Even during the span of the crimes, none of his associates witnessed Ramirez behaving in a violent or aggressive manner. He had no history of escape attempts or violence towards staff or guards in the courtroom. The petition states:

“prior to trial, the bailiff stated that many deputies had been in contact with Petitioner and that he was not violent.”

Claim 22 also covers the issue of the defendant wearing prison-issue garments – he or she has the right to the appearance, dignity and self-respect of a free and innocent person, but Richard also often wore a prison suit. Whether it was sometimes his choice or not, it did him no favours, especially as he failed to understand the impact of his appearance upon the jury.

“The foregoing violations of Petitioner’s rights had a substantial and injurious effect or influence on Petitioner’s convictions and sentences, rendering them fundamentally unfair and resulting in a miscarriage of justice.”

This is yet another example of Richard Ramirez’s dehumanisation before conviction.

-VenningB-

-

Spill-Over

This post will concentrate specifically on Claim 20 of the Writ of Habeas Corpus, filed in 2008: the trial court’s denial of the motion to sever unrelated incidents.

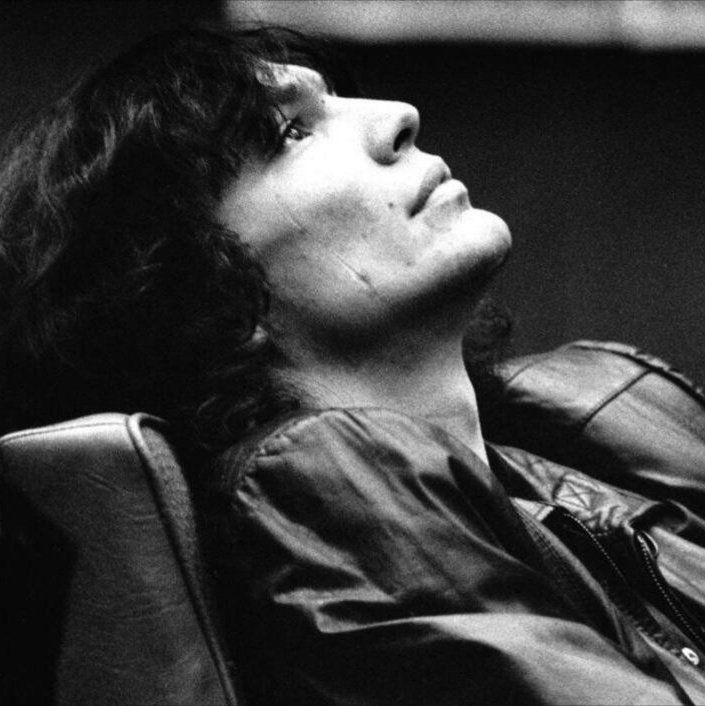

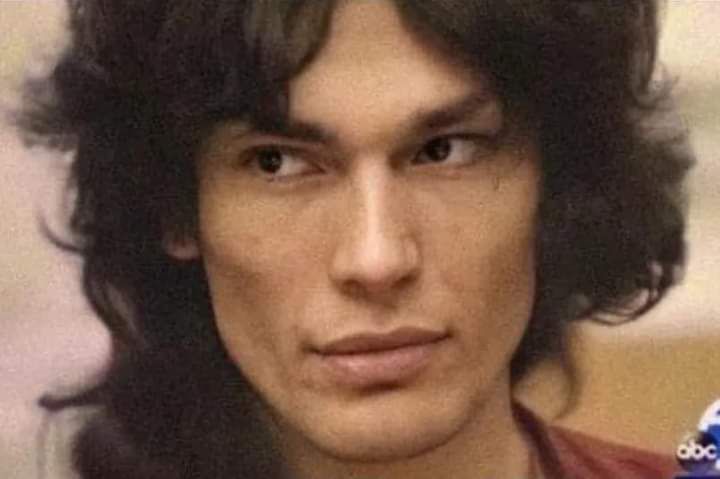

Richard, not looking particularly blonde or Asian, in court, despite eyewitness reports.

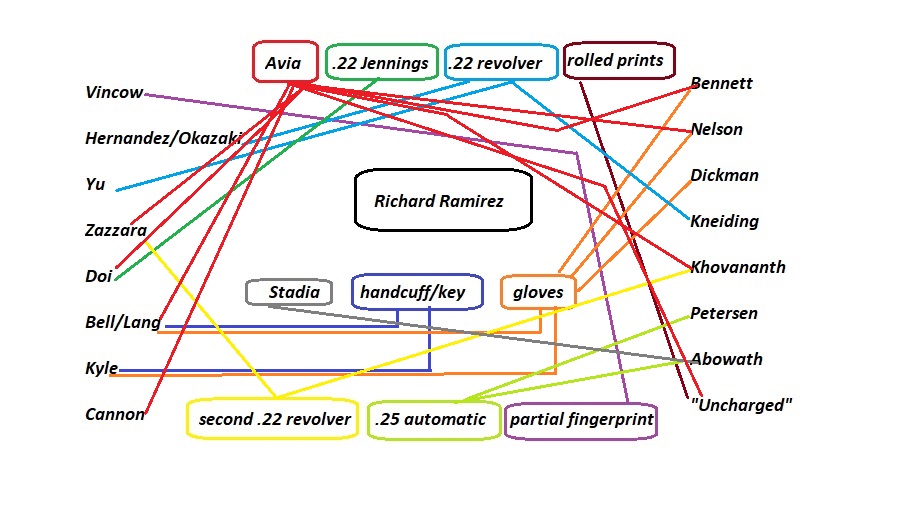

Facts: On September 30th, 1987, Richard’s counsel moved to sever counts compromising of fifteen incidents: forty-three charges and nineteen special circumstances. The grounds given were:

- The crimes were not connected in their commission.

- The offences were not cross-admissible.

They wanted to sever the charged crimes into eight separate trials, based on cross-admissibility of the evidence, as follows:

- Petersen and Abowath (common ballistics evidence)

- Hernandez/Okazaki, Yu and Kneiding (common ballistics evidence)

- Khovananth and Zazzara (common ballistics evidence)

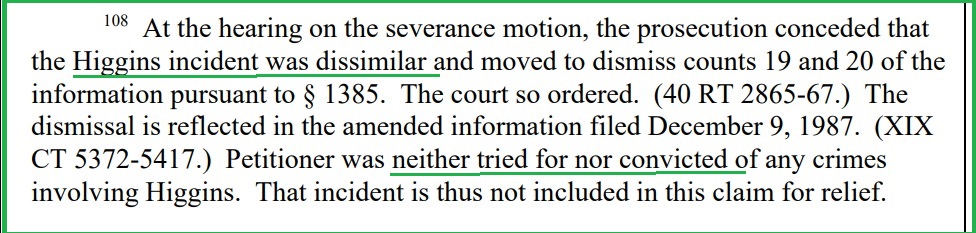

- ** Higgins (absence of any cross-admissible evidence) ** see note

- Vincow (absence of cross-admissible evidence)

- Bennett, Bell/Lang, Cannon, Nelson, and Doi (similar shoe print evidence)

- Dickman (absence of cross-admissible evidence)

- Kyle (absence of cross-admissible evidence)

** On December 9th, 1987, the court amended the charges, as counts 19 and 20 – Higgins – were dropped. There was not enough evidence to charge Ramirez, as the only thing linking him to the murder of Patti Higgins was the unreliable eyewitness from Arcadia, who said she saw him with a cat and a tub of ice cream (!) a few blocks away. Unsurprisingly, this bizarre sighting was never substantiated. No physical evidence was present. **

The prosecution conceded this, realising that it would cast doubts on other counts, where the evidence was also highly sketchy, and may undermine their case against Richard.

Writ of habeas corpus, claim 20

The court so ordered.

Despite the charges being dropped and no conviction made, Ramirez is forever guilty of this crime, regardless in the eyes of the world.

Counsel for the prosecution argued that all counts were joined correctly and cross-admissible: all crimes were of the same class.

Motion denied!

The consequences of this denial were, for Richard, massive and devastating; for the prosecution, like all their Christmases had come at once.

The physical evidence against Richard Ramirez was relatively weak; they relied on the joinder of offences with perceived strong proof to those with none or more invalid. Thus, making the inferred guilt more plausible and likely to the jury. In contrast, the State would have had problems proving a connection between the incidents if this motion had been granted.

The spill-over effect and its consequences

How did they do it?

It all seems so complete, so overwhelming, but is it? If we start to pull at the threads, the overall picture isn’t so obvious.

From the very beginning of the case, law enforcement had gone to some trouble to convince everyone that what was unique about the Night Stalker was his lack of modus operandi: he had no pattern. The prosecution had to do the opposite; they must convince a jury that there was a pattern, that all crimes were cross-admissible, and they would show how by linking crimes through ballistics, shoe print, unique wounding, and eyewitness testimony. For only through demonstrating this would a joinder be permitted.

In our previous posts we have shown how expert witnesses, retained by the habeas lawyers, examined the shoe print and ballistics evidence. Where the evidence presented by the prosecution was inaccurate and misleading. Please read the articles to avoid unnecessary repetition, but as a brief recap, the Avia prints were not unique and the firearms expert, in his declaration, advised that the ballistic evidence was faulty and needed retesting. This article discusses how it isn’t possible to even definitively prove that a certain bullet came from a certain gun.

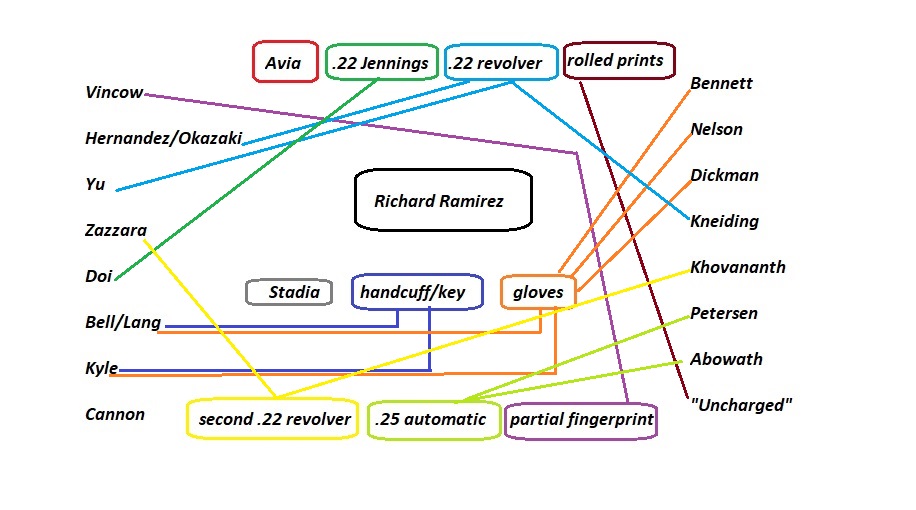

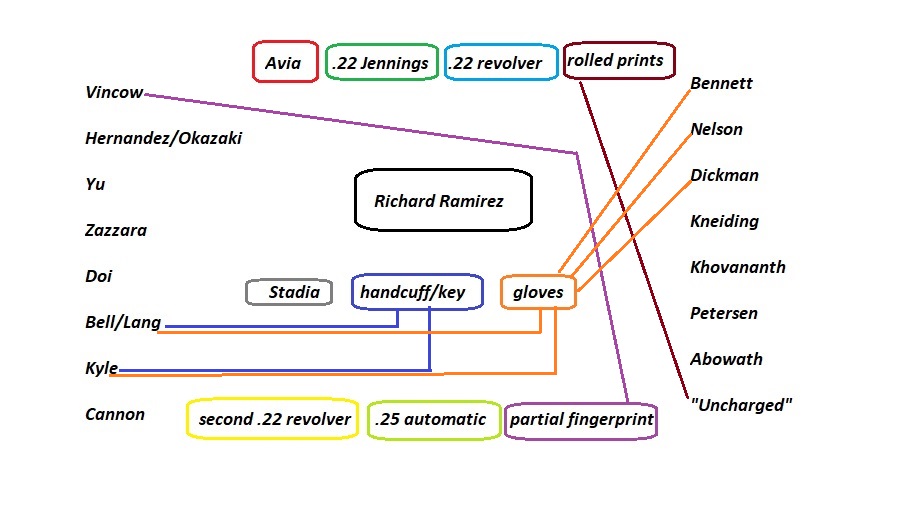

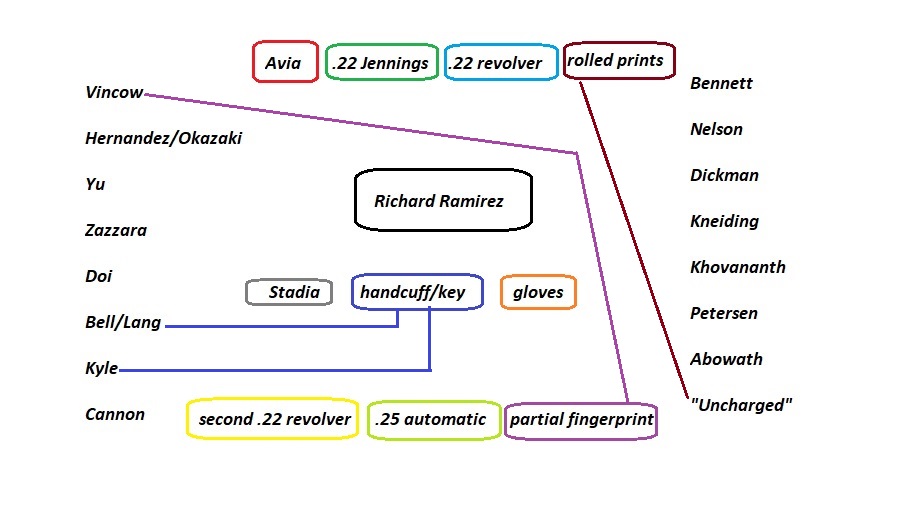

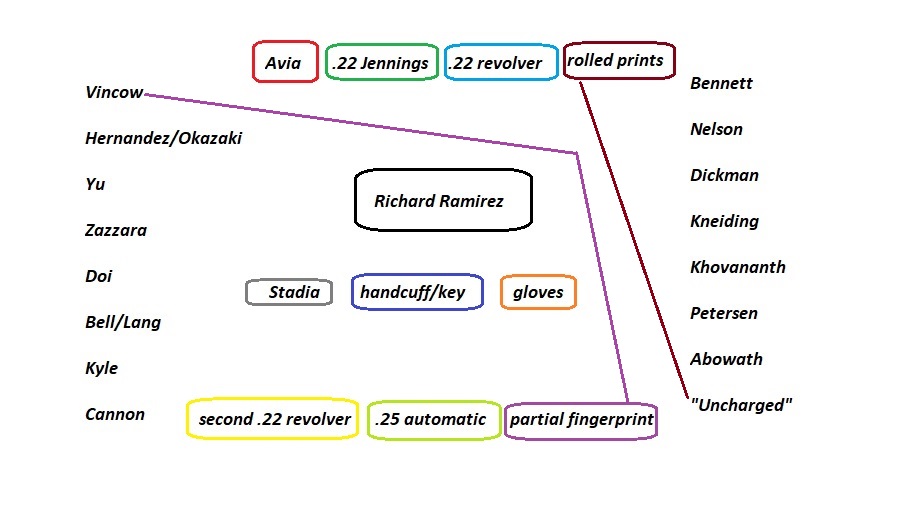

Here’s a chart, showing where and how each offence was linked. It’s quite a web, with Ramirez trapped in the middle, as the evidence is woven around him. * A desktop is advisable to view clearly. *

Swipe through the gallery above, and as the layers are removed, it becomes apparent why the joinder was necessary for the prosecution. *Note: Neither Mabel Bell nor Florence Lang were restrained by handcuffs, nonetheless, this is an accurate depiction of the linked incidents as produced in court by the prosecution.

Partial prints are inconclusive, and the prints at the “uncharged” remain the last layer. It’s a grey area, with different law enforcement agencies employing various techniques and requirements regarding how many loops and ridges are considered admissible evidence in court. As explained in the highlighted post, it is not an exact science and could have been quickly challenged, but of course, it wasn’t.

We are left with the rolled prints at the uncharged incident, allegedly lifted by the “enterprising” Officer Wright, who conveniently had all the fingerprinting technology in his regular (but amazingly equipped) patrol car, and who managed to do all the required forensic work, without calling in the specially trained officers who would usually attend a burglary, bringing in the tools needed to carry out the job. And no one is claiming that Richard Ramirez was not a thief!

His attorneys should have been able to challenge all the evidence. Still, as we have shown, the defence counsel needed help investigating or developing a defence strategy. Something needed to be more forthcoming to challenge or defend the case.

I have to keep referring back to what is central to the theme of this blog, the lack of defence. Not guilt or innocence but a failure of the system.

To quote Lt Dan Cooke from LAPD:

“Now begins the hard work of tying him to all the other crimes we’re looking at”.

Lt Dan CookeAs stated on our front page, shouldn’t that have been done already? If he was their only suspect? Primarily, he was already referred to as the Night Stalker by the slavering media.

His M.O was he had no M.O

To show a criminal identity via modus operandi, the evidence must show common marks, or “identifiers”, which together or singly show a “strong inference” that the defendant committed all the crimes so joined.

The People versus Bean

Writ of Habeas Corpus, claim 20, page 538

Richard’s case was so unusual and unique that once some evidence had linked him to one incident, the jury would presume his guilt on every charged crime. At the time of the court’s ruling, each joined offence was highly inflammatory, with the media already identifying him as the perpetrator of the four non-murder incidents. Before the farcical line-up, the police had already indicated to Carol Kyle that “the Night Stalker” would be there, adding to an already biased procedure.

The disparity between the strength of evidence between the murder and non-murder charges (remember, at this juncture, the prosecution holds those cards) would cause the impermissible “bootstrapping” or spill-over effects and inevitably lead to a conviction on all counts, regardless of the weak evidence.

Because there’s a road, near a road and it goes somewhere. This is a common mark?

By upholding the joinder, the trial court made it impossible for the jury to consider each count separately when weighing up the evidence, the inevitable spill-over, caused by the joining of all fifteen incidents, rendered them unable to compartmentalise. Putting this together with a total denial of effective defence at the guilt phase and lack of mitigation during the penalty phase, the likelihood of the jury considering evidence solely related to each separate offence was null and void.

The judicial economy was not an overriding concern. It should not have outweighed inflammatory evidentiary concerns or the spill-over effect. The court could have easily severed this case into four separate groups: the separate Vincow incident; those involving inflammatory evidence, such as mutilation and Satanism; incidents with minimal inflammatory evidence; and incidents in which no murders occurred.

Like this:

- The Zazzara, Bell/Lang, Cannon, Nelson, and Khovananth incidents.

- The Hernandez/Okazaki, Yu, Kneiding, and Abowath incidents.

- The Bennett, Kyle, Dickman, and Petersen incidents.

- The Vincow incident,

No safeguard against the spill-over

Even then, at this point, had Richard had a competent defence, a team capable of rebutting the charges, and providing their own expert witnesses, the evidence against him could have been challenged. This is one of the most infuriating things about this case and he, with his mental impairments, was seemingly oblivious, lacking the understanding that he was entitled to a strong defence.

Here, at least, they tried

Saying he was severely disappointed is a vast understatement, especially considering the implications. To properly examine the case, jurors must have both sides because that is how trials are supposed to work. What will they do if they are not shown anything in either defence or mitigation?

Had the defence counsel retained a criminal expert to show that the incidents were unrelated, the jury may not have been swept away by anger and revulsion. It may have been able to dispassionately categorise the incidents and considered more deeply that some of its members had specifically noted the eyewitness testimonies did not sound like Richard Ramirez at all.

The habeas lawyers did retain such an expert, and this is his conclusion:

Declaration of Steve Strong, expert witness, specialising in serial murder. Doc 7-21 A full breakdown of the findings of Steve Stong can be found HERE.

Richard with attorney Arturo Hernandez

“A jury consists of twelve persons chosen to decide who has the better lawyer”

Robert FrostAn uncomfortable truth.

~ Jay ~

You must be logged in to post a comment.