“The world has been fed many lies about me..”

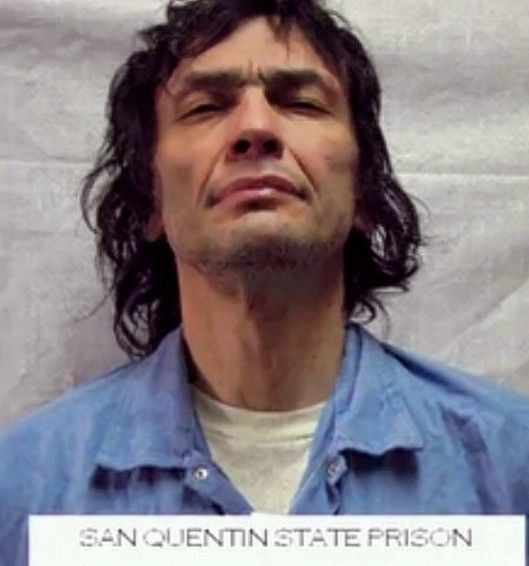

Richard Ramírez

Now available, the book: The Appeal of the Night Stalker: The Railroading of Richard Ramirez.

Welcome to our blog.

This analysis examines the life and trial of Richard Ramirez, also known as The Night Stalker. Our research draws upon a wide range of materials, including evidentiary documentation, eyewitness accounts, crime reports, federal court petitions, expert testimony, medical records, psychiatric evaluations, and other relevant sources as deemed appropriate.

For the first time, this case has been thoroughly deconstructed and re-examined. With authorised access to the Los Angeles case files, our team incorporated these findings to present a comprehensive overview of the case.

The Writ of Habeas Corpus

The literal meaning of habeas corpus is “you should have the body”—that is, the judge or court should (and must) have any person who is being detained brought forward so that the legality of that person’s detention can be assessed. In United States law, habeas corpus ad subjiciendum (the full name of what habeas corpus typically refers to) is also called “the Great Writ,” and it is not about a person’s guilt or innocence, but about whether custody of that person is lawful under the U.S. Constitution. Common grounds for relief under habeas corpus—”relief” in this case being a release from custody—include a conviction based on illegally obtained or falsified evidence; a denial of effective assistance of counsel; or a conviction by a jury that was improperly selected and impanelled.

All of those things can be seen within this writ.

The Writ of Habeas Corpus is not a given right, unlike review on direct appeal, it is not automatic.

What happened was a violation of constitutional rights, under the 5th, 6th, 8th and 14th Amendments.

Demonised, sexualised and monetised.

After all, we are all expendable for a cause.

- ATROCIOUS ATTORNEYS (4)

- “THIS TRIAL IS A JOKE!” (8)

- CONSTITUTIONAL VIOLATIONS (9)

- DEATH ROW (3)

- DEFENCE DISASTER (7)

- INFORMANTS (6)

- IT'S RELEVANT (17)

- LOOSE ENDS (15)

- ORANGE COUNTY (3)

- POOR EVIDENCE (16)

- RICHARD'S BACKGROUND (7)

- SNARK (12)

- THE BOOK (4)

- THE LOS ANGELES CRIMES (22)

- THE PSYCH REPORTS (14)

- THE SAN FRANCISCO CRIMES (5)

- Uncategorized (5)

-

You, the Jury

Questioning

The word “occult” comes from the Latin “occultus”. Ironically, the trial of an infamous occultist and Satanist is the epitome of the meaning of the word itself: clandestine, secret; hidden.

We’ve written many words; a story needed to be told, and we created this place to enable us to do just that.

Here, in this space, we intended to present the defence omitted at Richard Ramirez’s trial in violation of his constitutional rights. Our investigations have taken us down roads we’d rather not travel along, but as we did so, we realised that there was so much hidden we could search for a lifetime and still not see the end of it. Once we’d started, there was no turning back; we followed wherever it led.This was never about proving innocence; that was never the intent or purpose. We wanted to begin a dialogue, allowing this information to be freely discussed and for us to verbalise the rarely asked questions. We asked, and we’re still asking.

We can’t tell you, the reader, what to think; you must come to your own conclusions, as we did.

And so

We’ve said what we came here to say; with 114 articles and supporting documents, we’ve said as much as we can at this point.

This blog will stand as a record of that, and although we will still be here, we intend to only update if we find new information, if we suddenly remember something we haven’t previously covered, or to “tidy up” existing articles and examine any new claims (or expose outrageous lies) that come to light. The site will be maintained, and we’ll be around to answer any comments or questions.

What Next?

We will focus on the book being worked on; we’ve also been invited to participate in a podcast. When we have dates for those, we’ll update you.

The defence rests? Somehow, I sincerely doubt that; ultimately, we’re all “expendable for a cause”.

~ J, V and K ~

-

Ballistics Bollocks?

“In one response to a basic question about what the defendant does during the trial, Mr. Ramirez’s irrationality leaks through: “Sit and watch the whole facade – the stupidness of it. You have lay persons giving legal jargon that they don’t go to school for even and pretend to do scientific stuff.” When I asked to whom he was referring, his response was, “The jury!”. Mr. Ramirez’s ability to assist counsel in the conduct of his own defense is grossly inadequate due to the incapacitating effects of his mental disorder”

Report of Dr Anne Evans, forensic psychologist doc 16-7

As irrational as the statement above sounds, it holds some merit. A jury in a capital case has a defendant’s life in their hands; they must trust that the evidence laid before them by the prosecutors is reliable, and they should also be given counter-evidence by the defence. Juries are generally made up of “lay persons” in that, at least, Ramirez was correct. Evidence presented to them by expert witnesses holds high value, especially expert witnesses for the prosecution.

However, in the Ramirez case, as we have demonstrated throughout this blog, the jury was drip-fed misleading and often false, inaccurate information, whether regarding shoeprints or, in this instance, ballistics evidence.

In 1985, The Association of Firearms and Toolmark Examiners decided to develop a document on the theory of toolmark identification with a range of conclusions that could be reached from comparing toolmark evidence. Toolmarks are the characteristic markings picked up when bullets and casings are expended from guns. The result, produced in 1989, was unanimously accepted and approved by the AFTE. The lengthy summary can be accessed here.

From the National Academies Press

Linking the Crimes – The Findings of Deputy Sheriff Edward Robinson.

We are told that Ramirez owned a vast array of weaponry, which he often changed from crime to crime, sometimes during the same night when a double incident occurred. No guns (nor any other weapons associated with the Night Stalker crimes) were recovered, unless the carelessly lost Jennings is included, but that is another story and you can read it HERE.

The prosecution linked eight incidents (in the LA trial) through ballistics; the version of events produced in court is detailed below, an eventuality decided upon after the third firearms officer, Deputy Sheriff Edward Robinson, examined the distorted bullets and casings fragments removed either from the victims or the crime scene.

- .22 calibre revolver – Okazaki, Yu and Kneiding.

- .22 calibre revolver – Zazzara and Khovananth

- .22 Jennings semi-auto – Doi

- .25 auto – Abowath and Petersen (Pan – trial stayed indefinitely, Carns – uncharged)

Deputy Sheriff Edward Robinson worked in the firearms identification section; he became involved in the case in April 1986, almost a year after firearms officers Robert Christansen and Robert Hawkins examined the evidence. He was the one who gave the prosecution what they wanted, and consequently the only one called to testify; the other two firearms officers either didn’t agree with him or each other.

The Devil’s in the Detail – The Affidavit.

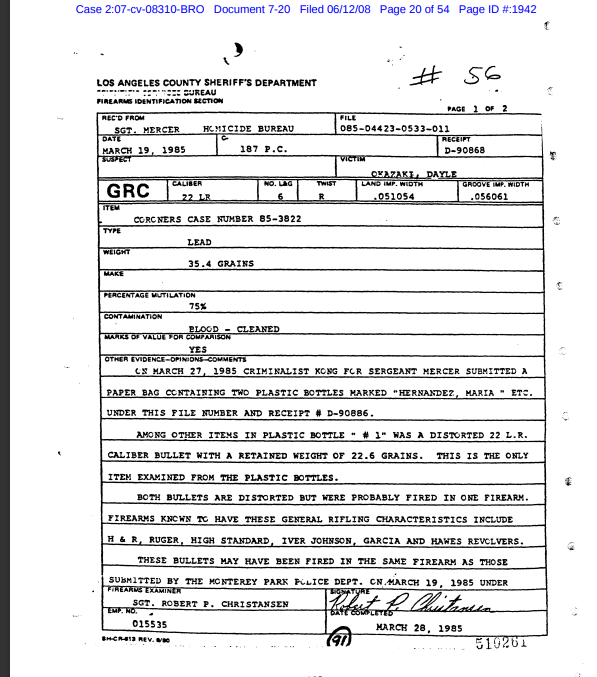

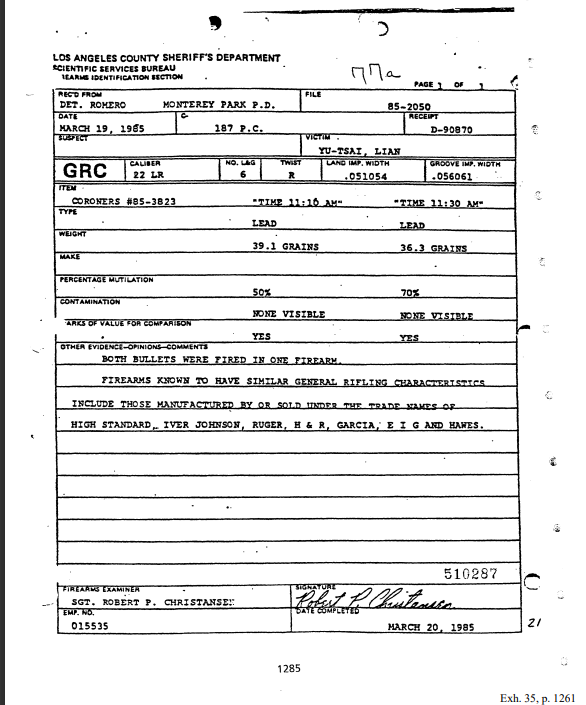

On 1st September 1985, an affidavit detailing crimes and the evidence against Ramirez was produced. The first firearms officer to examine the ballistics evidence, Sgt Robert Christansen, came to a different conclusion regarding ballistics. He received the bullets used in both the Okazaki and Yu incidents for testing on 19th March.

In a report prepared on 28th March 1985, Christansen states that the bullet removed from Dayle Okazaki was a .22 long-range lead bullet and suggested these brands of weapon (he could not be specific) H&R, Ruger, High Standard, Iver Johnson, Garcia and Hawes Revolvers. The bullet removed from Okazaki showed 75% mutilation and was too distorted to positively match it to the bullets from the Yu incident; those had shown 50% and 70% mutilation. He cautiously states that it “may” have been fired from the same weapon.

Report of Robert Christansen, document 7-20

Report of Robert Christansen, document 7-20 *Edit* In October 2025, we flew to Los Angeles, where we were granted permission to examine the case files kept in the basement in the Hall Of Records . Inside one volume, we discovered some interesting information regarding one ballistics examiner, Robert Christansen, and how Halpin defied the court and refused to bring him in to be questioned by the defence. You can read about that in THIS POST.

On 13th August 1985, a second firearms officer, Robert Hawkins, completed his examination of the bullets removed from Maxson and Lela Kneiding, along with some fragmented grains found in a rug. He discovered two .22 calibre gold-washed lead bullets, showing 60% and 75% mutilation. In his opinion, these matched the bullets from the murders of Okazaki and Yu on 17th March. He disagreed with Christanen on the type of weapon involved, stating that it was either a Remington or a Philippines Armscor.

Report of Robert Hawkins, document 7-20

However, in the affidavit, Christansen does not agree that the Kneiding bullets matched Okazaki and Yu; he believed they were from a .25 automatic.

“Sgt. Christansen examined the ballistics evidence from the San Francisco case [Pan] and the Mission Viejo case [Carns] and stated that the weapon that had fired the bullet in these cases, had also fired the bullets in the murders on 7-20-85[Kneiding and Khovananth] and assaults on 8-6-85[Petersen]”

Affidavit, document 7-4Robert Christansen concluded that the weapon used in the Kneiding and Khovananth cases (both 20th July) was a match to the gun used in the Abowath attack and murder, and all were .25 calibre bullets, matching the Carns and Pan incidents.

Robert Hawkins’ report and conclusions were not used in the affidavit, and probably due to this conflict of opinion, neither Hawkins nor Christansen were called to testify on behalf of the prosecution.

Hawkins did agree with Robinson that the bullets in the Okazaki, Yu and Kneiding murders were a match; both men thought the bullets were .22 calibre, fired from the same gun, although Robinson was unable to determine what brand“In Robinson’s opinion, a positive identification meant that a bullet was fired from a firearm ‘to the exclusion of all other firearms.’”

Habeas Corpus, page 106To come to this conclusion, surely Robinson would need access to the weapon in question; access he did not have.

“Projectiles in the Okazaki incident the Kneiding incident, and the Yu incident had identical characteristics: six lands and grooves with a right-hand twist, the most common characteristics of .22-caliber firearms. Robinson was unable to determine the manufacturer and exact type of firearm that fired the recovered bullets.”

Habeas Corpus, page 106Richard’s Habeas lawyers had this to say:

In the Kneiding case, firearms examiner Hawkins found there was 60% mutilation of an expended bullet but identified the bullet as having been fired from the same firearm as the bullets fired in the Yu case. This finding raises questions about the reliability of the testing”.

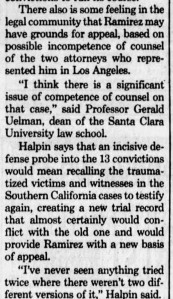

“Robinson was the last of three law enforcement firearms examiners to evaluate the general rifling characteristics of the ballistics evidence. Yet the two other examiners, who did not reach entirely the same conclusions, were not called to testify at trial. For example, in the report prepared by Robert Christansen on March 28, 1985, he concluded that due to distortions of the .22-caliber bullet in the Okazaki case, no positive comparison can be made to the Yu case.

Habeas Corpus, page 634

The Attempt to Link Zazzara to Okazaki and Yu Fails.

On 29th March 1985, Vincent and Maxine Zazzara were horrifically murdered in their Whittier home. On the 3rd of April, Robert Christansen compared the bullets from this case to the ones from the 17th March killings of Okazaki and Yu. In his report, filed on 12th April, he found the expended bullets too distorted to make a positive match, showing 70%, 85% and 90% mutilation. A bullet found on the floor was determined as too distorted to be of “any comparison value”.

Document 7-23, ballistics report “On 4-3-85, Sgt. Christansen of the Crime Lab, compared the bullets recovered from the victims to the bullets recovered at the Rosemead and Monterey Park murders. He related that due to the amount of distortion to the bullets, he was not able to match or eliminate them as having been fired from the same weapon.”

Affidavit, document 7-4It’s interesting to note that he was asked to compare these very different crimes; the “hitman-style” killing of Dayle Okazaki in no way resembled the on-street public murder of Tsai-Lian Yu, which, in its turn, didn’t resemble the brutal execution of Vincent and Maxine Zazzara. This supports the hypothesis that in late March, the idea of a “Serial killer” was already in place in the minds of detectives, confirmed by the unfortunate Arturo Robles, who was arrested and interrogated by Detective Carrillo on 10th April. “The word ‘serial killer’ hung in the air”, he recalled.

Petersen, Abowath, the Primer and the .25

Detective Carrillo likes to say, “His inconsistency was his only consistency”, and “His M.O. was no M.O.”, which gives much scope for linking crimes and making discernible patterns that must be shown for joinder of all offences. The physical evidence linking any Night Stalker crimes was relatively weak, so the reliance on the ballistics was paramount. Law enforcement emphasised the lack of modus operandi throughout their investigations, but the State needed to prove that there were links and cross-admissible evidence.

The Petersen and Abowath incidents were again totally dissimilar. However, law enforcement determined that the crimes had been perpetrated by the same assailant wielding the same weapon: a .25 automatic. It didn’t matter that the surviving victims had described completely different attackers, and eyewitness statements were duly changed to fit in with the image of the snaggle-toothed, maniacal Night Stalker; the ballistics evidence looked compelling as the expended .25s appeared to share the same red-coloured primer, discovered by Edward Robinson.

His report isn’t in the documents included in the 2008 petition, but we have a transcript.

“Robinson compared the bullet recovered from Elyas Abowath and a cartridge casing found at the scene (Prosecution’s Trial Ex. 40-G) with expended .25-caliber cartridge casings and a slug or deformed bullet in the Petersen incident (Prosecution’s Trial Exs. 38-B and 38-C). In Robinson’s opinion, the cartridge casings and bullets in both cases were fired from the same .25-caliber firearm. A .25-caliber weapon was not recovered. Robinson compared .25-caliber ammunition recovered from the Greyhound bag with .25-caliber long-rifle cartridge casings in the Abowath and Petersen incidents. In his opinion, the tool marks on the expended .25-caliber cartridge casings in those incidents were the same as the tool marks on the .25-caliber live ammunition from the Greyhound.”

Habeas Corpus, page 107These red-primed bullets were of an old variety and, as with the Avia sneakers, had to be extremely rare.

After his arrest on 31st August, Ramirez apparently told law enforcement that he had some belongings in a lock-up at the Greyhound bus depot; a bag bearing the name Greg Rodriguez was discovered, and among its contents, a box containing mixed bullets, mostly Remington .32s, but also three .25s, which appeared to share the same red primer as the ones from the Abowath and Petersen crimes. Why Ramirez had his “friend” Greg Rodriguez’s bag wasn’t established.

Credit: 4map.com Los Angeles City and its wider county were home to over eight million people in 1985. Yet in that vast metropolis, it is accepted that out of all those millions of people, only Ramirez had access to red-primed ammunition. It’s a reach, especially as the Petersen and Abowath incidents were at opposite ends of the geographical location given to the Night Stalker crimes, approximately 57 miles, and yet only one man had access to these particular bullets. Rare bullets and rare sneakers.

Stock image: this doesn’t even begin to show the huge sprawl of either the city or wider county.

Lead Analysis – Flawed Science

When a gun is fired, it leaves microscopic markings known as “toolmarks” on the expended slugs and casings. Forensic specialists collect these expelled projectiles either from crime scenes or from the victim; these are then sent to be tested by the firearms department. If they have access to a suspect’s gun, or at least a gun suspected of being used in a crime, they can test-fire the weapon and, from there, analyse the toolmarks created and compare it to the expended bullets from a crime scene. This is how they can conclude that the weapon matches the bullets in question.

No gun or weapon of any kind used in any of the Night Stalker attacks was recovered from Ramirez. The .22 Jennings semi-automatic linked to the Doi Incident and retrieved from the self-confessed “senile” ex-felon, Jesse Perez, was somehow lost. Which hardly mattered, considering that Perez first told the police Ramirez sold him the gun six to nine months before the Doi case happened.

Without these guns, they could not perform a test fire; they had no way of knowing who pulled the trigger. Distorted bullets do tell a story, but they cannot say to the examiner who fired them from a gun.

It was long assumed that bullets from the same box came from the same manufactured batch, and it was on this premise they used bullet analysis to convict. This is what happened to Ramirez; in the absence of a weapon, it was determined that the red-primer bullets, those at the Petersen and Abowath incidents, and those contained in the box obtained from the bag in the locker must have come from the same batch, contain the same chemical components, and been put into the same box at the same time.

We now know that that is not the truth, and the FBI stopped the practice of lead analysis after the research undertaken by the National Academy of Sciences showed how flawed and unsatisfactory comparative lead analysis testing was. For over 40 years, this has led to many wrong convictions.

“The committee also reviewed testimony from the FBI regarding the identification of the “source” of crime-scene fragments and suspects’ bullets. Because there are several poorly characterized processes in the production of bullet lead and ammunition, as well as ammunition distribution, it is very difficult to define a “source” and interpret it for legal purposes. It is evident to the committee that in the bullet manufacturing process there exists a volume of material that is compositionally indistinguishable, referred to by the committee as a “compositionally indistinguishable volume of lead” or CIVL. That volume could be the melt, sows, or billets, which vary greatly in size, or some subpart of these. One CIVL yields a number of bullets that are analytically indistinguishable. Those bullets may be packed in boxes with bullets from other similar (but distinguishable) volumes or in boxes with bullets from the same compositionally indistinguishable volume of lead”.

(National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2004.)*Note: CIVL means compositionally indistinguishable volume of lead.

For more information about the flawed science of ballistics, see this link.

The Defence Concedes

Richard Ramirez had the misfortune of being saddled with what is possibly the worst defence team in the history of crime, and that’s not an exaggeration.

The ballistics evidence should have been easy enough to cross-examine with success; after all, the three firearms officers who performed the ballistics tests could not agree on the outcome.

Did they try? Well, they did hire an expert witness of their own, a highly regarded firearms officer, Paul Dougherty. Then forgot to give him the evidence to be tested and failed to communicate with him.

Declaration of Paul Dougherty, document 7-20 During the cross-examination, Ray Clark failed to challenge Robinson’s testimony regarding the reliability of his testing. Late to the defence team, struggling and unprepared, Clark limited himself to a few generic questions concerning the ballistics tests

Habeas Corpus, page 418 The prosecution’s evidence regarding the ballistics was weak at best and had they thought about it, Richard’s defence team could have challenged the evidence presented in court. The ballistics evidence was not conclusive.

Habeas Corpus – Dougherty is Retained

For the purpose of Habeas Corpus, Paul Dougherty was again asked to examine the ballistics evidence, and his preliminary findings are revealing:

“161. During his preliminary evaluation, firearms expert Paul Dougherty found that faulty testing protocol rendered the evidence unreliable. (See Ex. 35, P. Dougherty dec., ¶¶ 4-5.) His opinion regarding validity of the testing results provides support for relief. Had trial counsel investigated and presented evidence challenging the accuracy and reliability of firearms evidence – instead of conceding the evidence – the result would have been more favorable as there would have been a reasonable doubt regarding the prosecution’s evidence.”

Habeas Corpus, page 424He believed the ballistics evidence was faulty, inaccurate, and unreliable. He thought it should all be retested.

Habeas Corpus, page 424 “1299. Competent defense counsel would have challenged the ballistics evidence and the lack of accuracy and unreliability of the prosecution’s findings. The findings were inaccurate. Firearms expert Paul Dougherty has stated that there are internal conflicts in the reports of various law enforcement examiners and the evidence should be retested. (Ex. 35, P. Dougherty dec., ¶ 4.)

Habeas Corpus, page 424

Carrillo

In this video clip, Carrillo seems to infer that they knew the ballistics evidence was faulty but that it didn’t matter because they had the weapons in question. That is genuinely perplexing. They did not have guns, and no weapons were produced in court other than a brief appearance of the vanishing Jennings. If the prosecution had the weapons, did they simply “forget” to produce them?

The stories change month by month, and nothing is said about them by anyone who invites him along for a chat.Credit: Matthew Cox Podcast

An Afterthought..

Ballistics are often used to convict, but rarely to exonerate. Unless you are a cop working for the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department in 1988/89 who has been arrested for killing prostitutes. Ballistics testing on the gun found in his car linked him to three murders and so Rickey Ross spent some time locked up in LA County Jail in the same section as Richard Ramirez. Later, those ballistics tests were found to be “faulty and unreliable” and he was released.

Quelle surprise – but that is a story for another time.

Additional source: FBI — The Basis for Compositional Bullet Lead Comparisons, Forensic Science Communications, July 2002

~ Jay ~

-

Murder in Lake Merced

San Francisco‘s Golden Gate Bridge Peter Pan and his wife, Barbara, lived on Eucalyptus Drive in the Lake Merced area of San Francisco. Around 10 a.m. on August 18, 1985, their son stopped by their home and found Peter Pan had been shot and killed, and Barbara had been brutally attacked and sexually assaulted. The house had been ransacked. Initial news articles report the Pan’s son as having said his parents didn’t own anything distinctive or unusual and that nothing was missing from the home. However, later news reports would state that jewelry had been stolen.

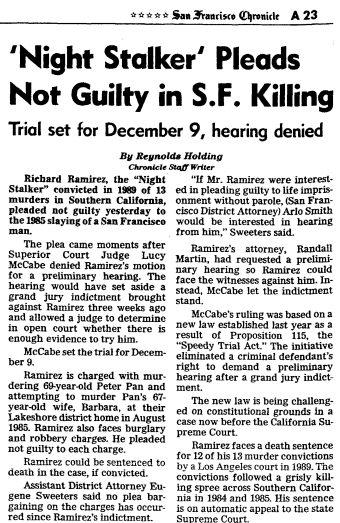

After Richard Ramirez was convicted and sentenced to death at his Los Angeles trial in November 1989, he was transferred to San Quentin State Prison’s death row. But legal proceedings against him were not over. San Francisco Assistant District Attorney Eugene Sweeters and his supervisor, San Francisco District Attorney Arlo Smith, had every intention of prosecuting Ramirez for the 1985 murder of Peter Pan and the assault on Barbara Pan.

The San Francisco case against Richard Ramirez is shrouded in secrecy as the court documents are not available to the public. So, we can only speculate as to what evidence law enforcement may or may not have had against Richard. There is only a small amount of information contained in a few news sources from the time. Even those must be taken with a “grain of salt” as San Francisco Police, the media, and the community in general were biased against Richard, and his guilt was assumed.

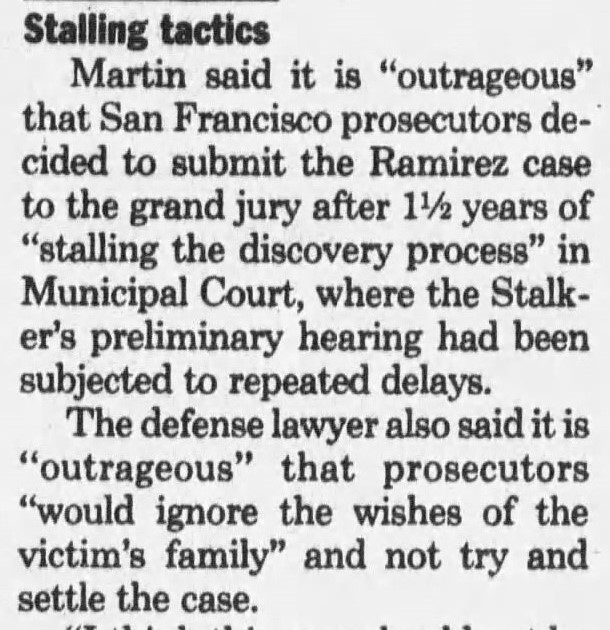

Timeline of events per the San Francisco Examiner & the San Francisco Chronicle

Richard first appeared in San Francisco Municipal Court for the Pan crimes on December 5, 1989. Other than the Hernandezes, yes, the same ones that did a deplorable job of “defending” him on the Los Angeles charges, showing up and insisting they were going to defend Richard in San Francisco, nothing noteworthy is reported other than an arraignment date being set for January 1990. After this, much of what appears in news articles indicates a series of delays and postponements that hindered the discovery process and eventually culminated in the case never going to a preliminary hearing but instead being submitted to a grand jury for an indictment.

- December 5,1989-Richard’s first appearance in San Francisco Municipal Court on charges for the murder of Peter Pan, assault on Barbara Pan, and burglary. The arraignment was postponed to January 5, 1990.

- February 5, 1990-Richard pleads innocent to SF charges/Randall Martin of the San Francisco Public Defender’s office was appointed his attorney.

- March 30, 1990-Preliminary hearing set for June 25, 1990.

- June 8, 1990-Preliminary hearing postponed to July 25, 1990.

- September 1990-Preliminary hearing set for October 5, 1990.

- October 1990-Preliminary hearing delayed to March 5,1991

- April 1991-Preliminary hearing postponed.

- May 13, 1991-After over a year of delays in proceedings at the San Francisco Municipal Court, a San Francisco grand jury indicted Richard on charges of murder, rape, assault, and burglary.

- June 6, 1991-Richard pled not guilty to SF charges. The attorney’s request for a preliminary hearing was rejected. A trial date was set for December 9th.

- January 8, 1993-Due to defense discovery motions, a San Francisco Superior Court judge postponed Richard’s SF trial. Nearly four years after Richard first appeared in a San Francisco court, the LA district attorney’s office had yet to turn over all documents relating to the so-called Nightstalker investigation to Richard’s San Francisco attorneys, causing more delays.

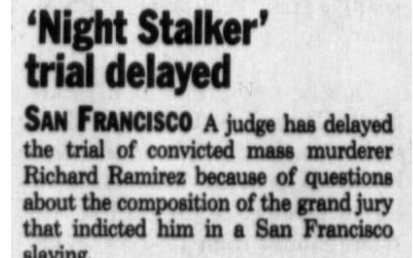

- March 8, 1994-Trial delayed again due to concerns with the grand jury that handed down the indictment.

- 1995-San Francisco trial proceedings stayed indefinitely.

San Francisco Examiner, May 12, 1991

Without presenting too much legal jargon, a few definitions may be helpful to have a better understanding of the San Francisco proceedings.

- Preliminary hearing-like a mini-trial, the prosecution calls witnesses and introduces evidence, and the defense can cross-examine witnesses. Richard did not have a preliminary hearing in San Francisco.

- Grand jury– a group of citizens authorized to conduct legal proceedings and determine whether criminal charges should be brought against someone. The grand jury indictment is drafted by the prosecutor and presents only the prosecution’s case. No judge, public defender, or criminal defense attorneys are allowed in the grand jury room. Grand juries convene in secret, and a unanimous decision is not required. After receiving a decision from the grand jury foreperson, the prosecutor can skip the preliminary hearing and proceed directly to trial. The defendant does not know the evidence being considered, does not have a right to be present, and cannot question the evidence early in the criminal justice process. The grand jury can end up being a tool of the prosecution, and the prosecutor can choose to withhold evidence that is favorable to the accused.

- Grand jury indictment–formal criminal charges are brought against a defendant. The indictment is merely a charging document used to bring a defendant into court to answer criminal charges. It is not evidence.

**We can only assume more delays and postponements occurred between 1994-1995, as no additional information appears in the San Francisco Examiner or other area newspapers regarding the SF charges or trial. **

San Francisco Chronicle, June 7, 1991 The Grand Jury Indictment

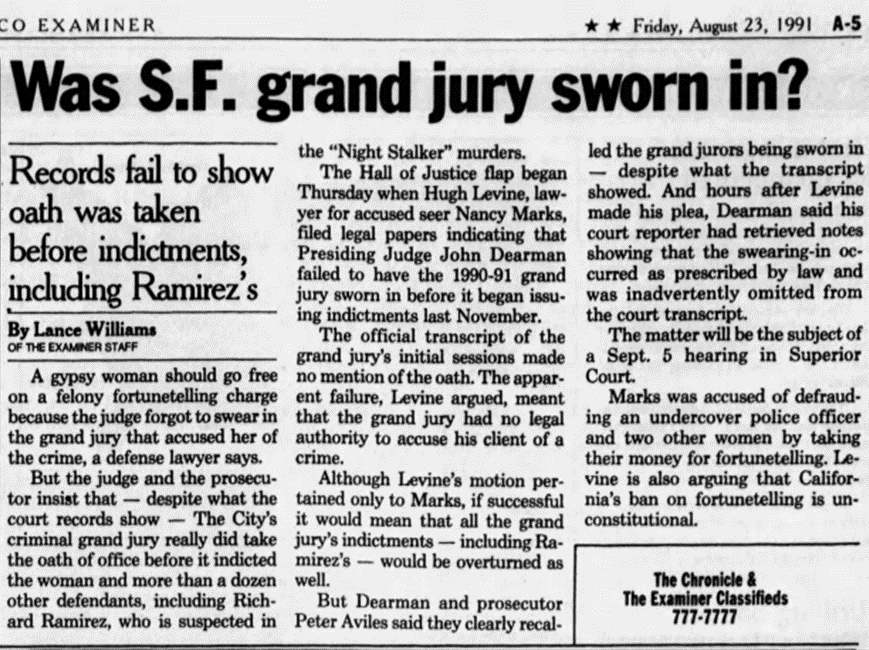

A defense attorney not on the Ramirez case, but assigned to a different case in which the same grand jury also indicted his client, brought forth claims that the grand jury had not taken an oath and been sworn in. Therefore, the attorney claimed that his client should go free. If this was true, every other person indicted by this grand jury, including Richard Ramirez, should not have been charged.

An article in the San Francisco Examiner from August 23, 1991, questioning the validity of the grand jury indictment.

San Francisco Chronicle, March 8, 1994 (3 years after the grand jury indictment the legality was still being questioned). Negative Impact of Grand Juries

A grand jury is a one-sided proceeding in that the defense attorney is not allowed to present evidence, cross-examine witnesses, or argue for his client. Consequently, grand jury indictments are relatively easy for a prosecutor to obtain. Suppose the grand jury decides the prosecutor has presented sufficient evidence to support a belief a person has committed a crime. In that case, it returns an indictment charging the person with that crime. Typically, a trial follows the grand jury indictment. What appears to have happened with Richard’s case is that he was indicted by the SF grand jury, never had a preliminary hearing, and the district attorney was planning to take the case straight to trial (with Richard’s case, there was no trial after the grand jury indictment).

Because there was no preliminary hearing, Richard had no idea who testified against him, or what was said, and he would not have known what so-called evidence was being used against him.

Was District Attorney Eugene Sweeters “Soft on Crime?”

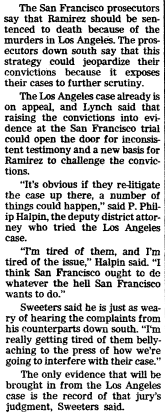

Eugene Sweeters was the San Francisco Assistant District Attorney that was adamant about prosecuting Richard Ramirez for the Pan crimes even though Richard had received 12 death sentences at his LA trial. Some of his colleagues, specifically LA trial prosecutor Philip Halpin, questioned why Sweeters was pursuing the charges against Ramirez. Halpin felt strongly that the SF charges should be dropped as he was concerned that if the LA witnesses were required to testify in SF, there would be a conflict between the testimony they gave in LA and what they might give in SF. Sweeters response to Halpin was there was “no chance” he would drop the SF charges. Despite pushback from law enforcement and members of the community, Eugene Sweeters would not give in to the demands of those who opposed his decision to take Richard to trial for the Pan crimes. San Francisco Examiner February 3, 1991

District Attorney Cat Fight

San Francisco Chronicle, May 17, 1991 LA attorney Philip Halpin was very concerned that assistant district attorney Eugene Sweeters would not drop the Pan charges against Richard, despite the effect it could potentially have on the LA convictions and the Pan family wanting to settle the case out of court. Apparently, Halpin wasn’t just concerned that the LA victims might have to appear in SF court, but he was worried that the LA trial would be closely scrutinized. But if the LA cases were airtight, what did Halpin have to be concerned about? That’s just it. Nothing about Richard’s LA trial or convictions were airtight and Halpin knew it. Newspapers also reported speculation from legal experts who felt the LA convictions might be overturned on appeal because of incompetent attorneys.

San Francisco Examiner, February 3, 1991Although we do not know specific details of the grand jury indictment or what occurred during the multiple SF court hearings, we know at the end of the day, the San Francisco district attorney stopped trial proceedings against Richard. Eugene Sweeters was unyielding in pursuing charges against Richard and bringing him to trial for the Pan crimes, despite the Pan family and many members of law enforcement not wanting a trial for someone who was already on death row. Something significant must have occurred to sway him from the course of action he was determined to carry out. What was it that persuaded Eugene Sweeters to cease proceedings? We do have an answer to this question. The mental health and psychosocial history developed by San Francisco Public Defenders Randall Martin, Daniel Inouye, and Michael Burt concerning Richard was very detailed with compelling supporting evidence. Eugene Sweeters feared if he moved forward with a trial in SF, Richard’s attorneys would use this information and get the SF charges altered or dropped.

The SF charges against Richard were stayed indefinitely, meaning he never had a trial to determine whether he committed these crimes. The San Francisco District Attorney did not stay the charges against Richard because he was “soft on crime.” The reason the SF charges were indefinitely stayed is because of the social and medical history that San Francisco Public Defenders developed and presented to the courts. Eugene Sweeters knew that if he took Richard to trial for the Pan crimes and his attorneys brought forth the evidence regarding Richard’s mental and physical health and his psychosocial history, this would very likely have been used to present an “insanity defense” or a “not competent to stand trial” approach, meaning the effect of the evidence presented in San Francisco would have affected all of the LA convictions, with a reasonable possibility of overturning the LA verdicts. Because if Richard wasn’t mentally competent at the time of the Pan crimes, then he could not have been mentally competent at the time of the other Night Stalker crimes. Regardless of what you may have read or heard elsewhere; this is an accurate account of what happened with the SF charges against Richard.

Let me reiterate this: Richard was never convicted of murdering Peter Pan, assaulting Barbara Pan, or for the burglary of their home. Anything you have read suggesting otherwise is based on a false narrative and is not true. Don’t believe everything you read or hear about this case.

2008 Federal Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus, Document 14 Unanswered Questions

Perhaps one of the things we should consider is why attorney Philip Halpin was concerned about the LA trial and verdict being analyzed? There should have been no worries if the LA charges and evidence were legitimate. If the Los Angeles Police and Sheriff’s Departments conducted a thorough, top-notch investigation, then they should have been confident that the convictions would hold up and not be overturned. Apparently, Halpin and other members of law enforcement did not have faith in their case or the evidence they presented. If one takes a good look at exactly what they presented to the jury, you will see that most of it does not hold up to scrutiny, was false and deliberately misleading.

A brief explanation of what a legal “stay” is

There are two main types of legal stays: a stay of proceedings and a stay of execution. A stay of proceedings refers to an order by a court stopping the actions of an entire case or a specific process within a case. A stay-in-execution court order refers to suspending the implementation of a ruling by a court. A stay of execution may be granted when a court allows an additional appeal by a prisoner and may also refer to a halt in carrying out a death penalty sentence. Richard received both types of stays: an indefinite stay of proceedings in his San Francisco case and a stay of his death sentences, as his 2008 federal Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus was making its way to the United States Ninth Circuit Court.

KayCee

Nov 25 2023

-

A Web of Informants: Part 5. Eva Castillo

Eva Castillo was named by Manuel Hechavarria (Cuba). He guided detectives to her last known residence but she was not there – she had been arrested for burglary in September 1984 and was in prison, using the alias Rosa Solis.

When detectives interviewed Castillo in prison, she admitted to committing burglary with Cuba and someone called “Charlie.” She also named “Julio” and mentioned that he lived with two brothers. She admitted committing burglary with Julio.

Castillo said she had known Ramirez since July 1984, and that he was nicknamed “Despeinada.” She did not have much to do with him because he was “dirty” (probably referring to his methods as opposed to his hygiene) and because he injected cocaine (she preferred heroin). She claimed to have done ‘speed balls’ with him, and they had shared a needle. Castillo described Ramirez as “jumpy,” and his technique “messy” and that “he stole too small things to be of any value.” She said he sold these goods at various pool halls. They purchased drugs at the same places: the Lincoln Hotel and the Traveler’s Hotel. For someone who never worked with Ramirez, and had only met him eight weeks earlier, Castillo certainly knew a lot about his burglary M.O. Perhaps she was lying about the length of time she had known him.

Castillo said that she witnessed Ramirez committing auto burglary near the Greyhound bus station after another criminal suggested stealing a car. She said that the fellow burglars were furious with him, believing that he would bring the police down on their little ‘community.’ His recklessness as well as his lack of skills at the ‘craft’ certainly gave criminals the motive to report him to the police. Richard Ramirez was the weak link and expendable.

Eva Castillo then revealed she was due for release on 6th October 1985 and had been paroled to Felipe Solano’s house – it always comes back to that man.

Eva Castillo is Missing

Like Alejandro Espinoza (yet another person who named Felipe Solano), Eva Castillo disappeared. This is a pity, because she would have been useful for the defence argument, because she had corroborated Sandra Hotchkiss’ description of him as an inept burglar. Also, she too had named Julio – somebody the police should have investigated. This means she was aware of other people who traded with Felipe Solano.

Ramirez claimed to have been a runner of stolen goods on behalf of Solano – he said these items he sold on had been stolen by Castillo and that he had taken them into Tijuana as a favour. According to Philip Carlo, Ramirez hoped they would be able to locate her, “to show what a lying creep Solano was” (page 340). However, Ramirez’s defence team was useless and Castillo was never found.

There was something very odd about her disappearance, however. As mentioned above, Castillo was paroled to Solano’s address. At trial, a correctional officer, Alex Lujan, testified as much, stating that he had called Solano’s house to double check that the address was legitimate. Solano’s wife took the call and informed Lujan that Castillo was not there. Conveniently, the prosecutor Halpin ‘forgot’ his files and so Lujan’s cross-examination was postponed. Days later, when Lujan returned to the witness stand, he changed his story. Now it ‘was all a big mistake’ and Castillo was not paroled to Solano’s at all. Instead, he claimed that Castillo was supposed to be deported to Mexico, had absconded and was now a fugitive. It is profoundly suspicious for such a key informant in the Night Stalker case to mysteriously disappear and suggests that Halpin used the ‘forgotten files’ as an excuse to go away and concoct a new story with his witness.

During Felipe Solano’s testimony (which will be covered in Part 6), he lied about ever receiving stolen goods from Castillo, but it was spun into a magnanimous act rather than perjury. This will be discussed in the next section.

-VenningB-

21st November 2023

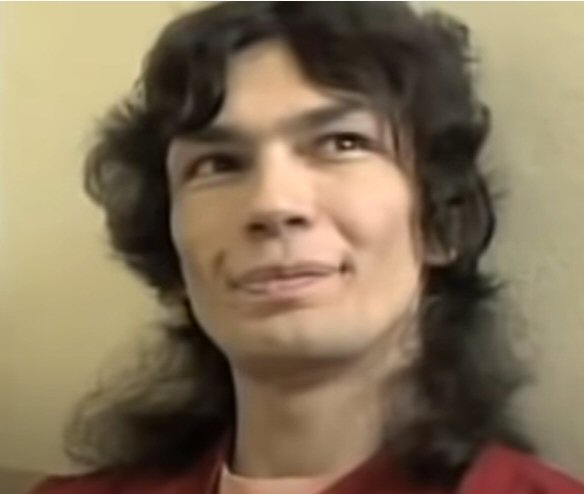

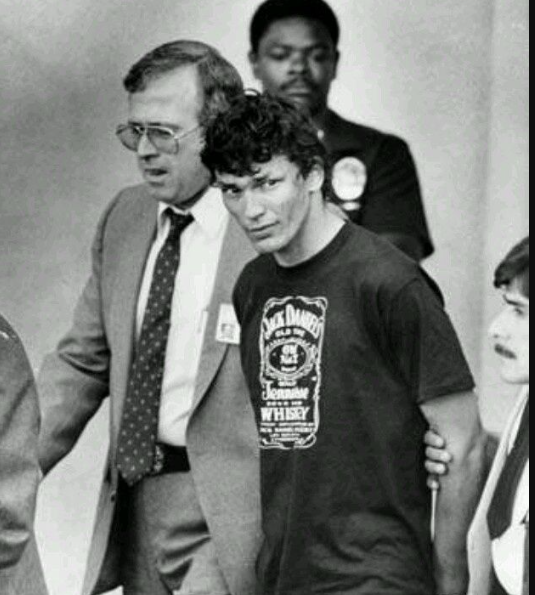

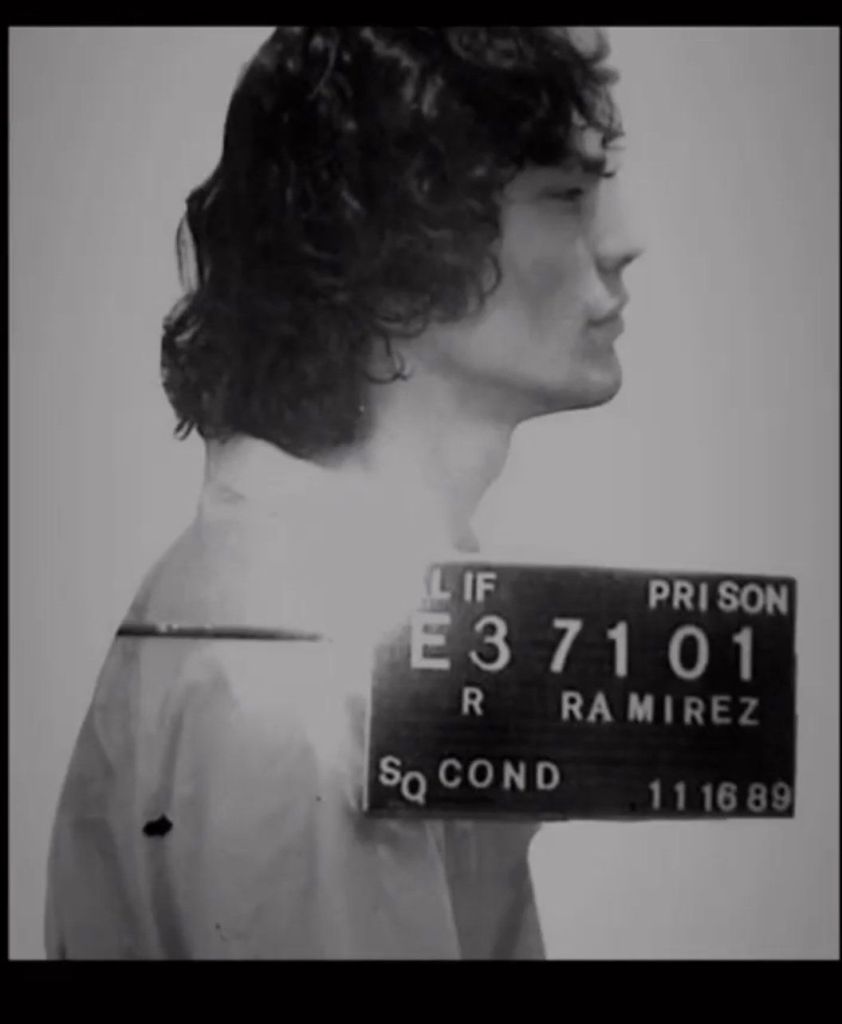

Ramirez in 1984 -

Family Matters – Part Two

Note: Richard’s early years have been covered here, detailing his various head injuries, physical and mental problems, and his time in the custody of the Texas Youth Council, so I need not repeat that. Likewise, the influence of his infamous cousin, Miguel, and the associated trauma and violence. Please see the posts indicated for more information on those matters.

*Some images may appear small, a desktop is advised*

“No one from Richard’s trial defense team asked me to testify at Richard’s Los Angeles trial. Had I been asked, I would have willingly provided the information contained in this declaration to anyone from his legal team prior to the trial. Had I been asked, I would have testified to the information in this declaration at Richard’s murder trial in Los Angeles.”

Statement of Mercedes Ramirez, document 20-5Following on from Part One, the information within this post can be found in documents 7-19, the declaration of Marylin Cornell, from her interviews with the Ramirez family, and from the family statements, documents 20-5 and 7-30, and also 20-8. All are exhibits to the 2008 Writ of Habeas Corpus.

Culture Clash

According to Cornell, life did not get any easier for the Ramirez family; for Julian Snr., Mercedes, and their growing brood of children, with their psychological, neurological and physical needs, it meant that trouble was never far from the door.

Cornell states that the Ramirezes had difficulty settling into their new environment, partly adhering to their Mexican roots and ways, whilst working and trying to accommodate a change in culture and language, and although Mercedes was born in Colorado, she spoke no English, her parents having relocated back to Mexico when she was a child.

Like many immigrant families, the Ramirezes had a deep mistrust of authority, which was deeply entrenched after an incident in the early 1950s when the border patrol mistakenly believed they were illegal immigrants and physically drove them back across the border, dumping them, their bags, and their small children by the side of the road in Juarez. Mercedes, so cowed by these government agencies, could not articulate that she was a citizen of the United States and that they had every right to be there.

It was two years before Julian Snr. could sort out his paperwork, enabling them to return.

Report of Marylin Cornell, document 7-19.

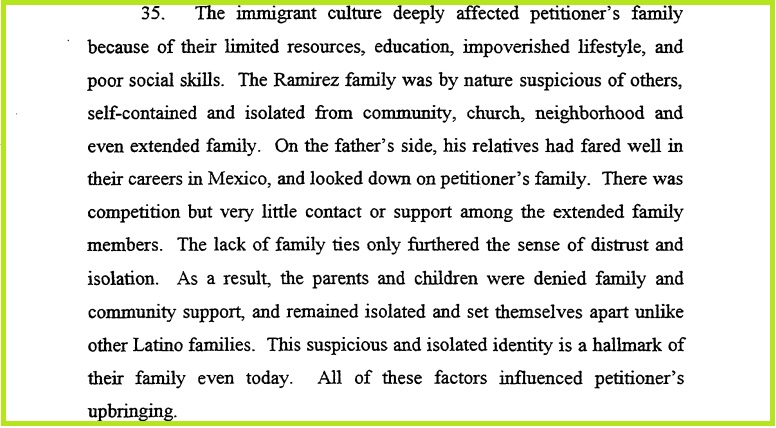

It seems that from her interactions with Richard’s family, Cornell believed they were somewhat isolated and kept themselves to themselves within a social context; she says that Julian Snr.’s family back in Mexico, who were faring well for themselves, looked down on their extended family in El Paso, and offered little or no support. At the time of the Ramirez family interviews, she believed that the family still carried that hallmark, which is unsurprising considering they bore the notoriety of the connection to Richard daily. Why would they trust anyone?

“In my contact with the family, I viewed the only photo album that exists from petitioner’s childhood. It documents only two family celebrations. The Ramirez family was not involved in social activities, after school activities, sports, or even church events. “We keep everything in the family,” according to Ignacio.”

Report of Marylin Cornell, document 7-19.Mercedes had taken on more and more with each pregnancy and had to work long hours to help provide. She struggled to assimilate into her new culture and surroundings, often finding comfort and familiarity in what she knew: her family’s traditions and cultural background. Distrustful even of medical practices, Richard and his brother Ignacio were taken to see a traditional healer/shaman in Juarez to receive injections, although they were not sure what they contained.

“Petitioner’s family believed in superstitions and folk medicine. The family felt they could only go to Mexico for medical help. They relied on unproven medical cures in Juarez, Mexico, and received injections without knowing what they were. As a child, Petitioner, his father, and Ignacio travelled to Camargo for healing rituals with a curandero.”

Report of Marylin Cornell, document 7-19

Mercedes and Julian Snr. embodied the strict Latino culture that they had been raised in, which sat awkwardly on the rebellious sons, who spent their teenage years in and out of trouble.Often away working, Julian Snr. came home to hear a litany of misdeeds attributed to his children.

Dynamics and Dysfunction

“After Miguel killed his wife, Josefina, Julian Snr. applied to the courts to adopt Miguel’s young children; he was turned down; the judge refused, stating that the Ramirez family had enough trouble raising their own sons”.

Report of Marylin Cornell, document 7-19.That Julian Snr. was a strict disciplinarian, no one is denying. However, there is one thing I will address right now: the often-told story of him tying Richard to a cross in a cemetery as punishment. That never happened; it’s one more exaggeration in the story, which a Ramirez family member has confirmed. By choice, Richard took himself off to a cemetery (probably the the Evergreen as that was where he used to hang out with friends) to avoid his father and any discord at home.

And discord there was.

“Petitioner was also subjected to the abusive and neglectful treatment of his older brothers. Petitioner’s brother Julian Jr. abused Petitioner when he was a young child, and Petitioner’s sister Rosa tried to protect him from the brothers’ abuse. Petitioner’s sister sought to care for him and protect from his older brothers. After Rosa left home, she allowed Petitioner to stay at her home. Rosa knew that Petitioner was having difficulties at home as well as at school”.

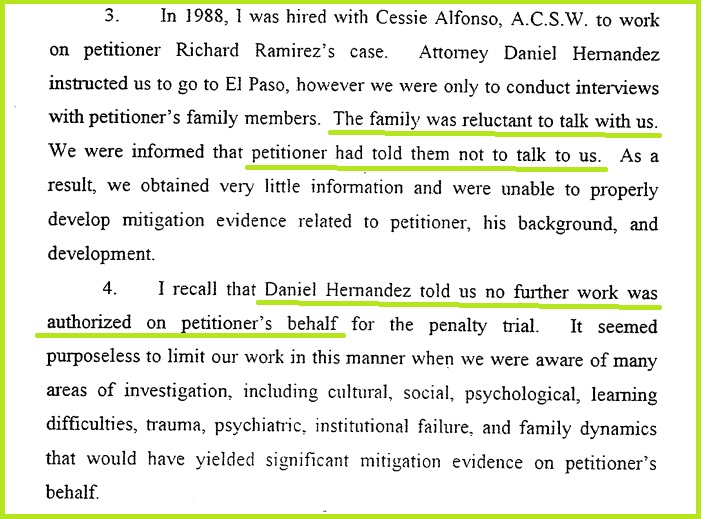

(Ex. 32, M. Cornell Dec., ¶ 59; Ex. 67, J. Ramirez, Jr. Dec., ¶ 7; Ex. 70, Rosario Ramirez Dec., ¶ 2.) Writ of Habeas Corpus, page 496In 2004 and 2008, immediate members of the Ramirez family gave a series of statements to Richard’s post-conviction lawyers. The information within should have been collated for Richard’s trial in 1989 to be used in mitigation during the penalty phase. Still, as we’ve shown, Ramirez was given no mitigation in defence. This was partly his doing because he refused to let his family be investigated or involved at any stage of the proceedings. He became distraught when his father was called to testify in court. His lawyers, rather than overrule him and do it anyway (they were supposed to be saving his life at this stage), had made a half-hearted attempt in 1988 by sending two social workers to El Paso to talk to Richard’s family about his upbringing, culture and family dynamics, plus any psychological and learning difficulties experienced by him.

Unsurprisingly, Ramirez, prone to self-sabotage, primarily where his family was concerned, allegedly called ahead and forbade his family to talk to them.

Here is the statement of Katherine Bauer, one of the social workers sent by Daniel and Arturo Hernandez. You can sense her frustration.

Declaration of Katherine Bauer, document 7-4. Here, then, are the statements and recollections the Ramirez family, which can be read in full in documents 20-5 and 7-30, exhibits to the Writ of Habeas Corpus

Crime and Punishment

“Julian Sr. always tried to keep the family unit self-contained. On

Report of Marylin Cornell, document 7-19, page 24.

petitioner’s arrest, Julian Sr. got his gun and wanted to kill himself because of the shame to the family“.Julian Jnr.

“By the age of 16, I began to use drugs on a regular basis. I have been involved in drug usage for many years. As a result of my addiction, two of my children were removed from my care and placed in foster homes. Despite the loss of my children, I was unable to stop using drugs for a lengthy period of time. I have had numerous arrests since 1968, mostly for drug charges, theft-related offenses, and domestic violence. I have spent time in jail in California over the past 30 years. As a result of my lifestyle, I have been unable to find work except for menial labor. I did not have a place to live or a family to support me”.

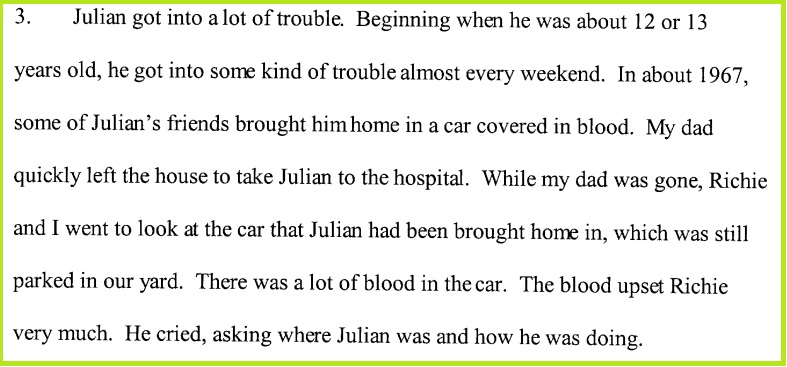

Statement of Julian Ramirez, document 7-30Julian goes on to say how he and Robert would beat and kick Richard as a child, the parents not being around to control or intervene. In her report, Cornell explains how Rosa would try to protect Richard from his older brothers.

Both Julian Jnr. and Robert were regular substance abusers; with these role models during his formative years, it is no surprise that Richard followed suit. Whether for self-medication or recreation, he was, by his early teens, using drugs daily.

Statement of Rosario Ramirez, document 20-5. Robert

Statement of Robert Ramirez, document 20-5 Note: Of the siblings, Robert goes into the most detail concerning violence in the home. However, Robert is also the one who tells a story about the supposed killing of a police dog by his brother Richard. Another member of the family has unequivocally denied this; other factors raising doubt on this accusation is that killing a police dog is a criminal offence and, as such, would appear in Richard’s records. We have found no such record. What we did find was a statement mentioning Robert’s penchant for setting fire to cats.

Statement of David Palacios, document 20-8. In his statement, dated 19th November 2008, Robert recalls his father, Julian Snr., working away and only returning home for a couple of nights every two or three weeks. On his return, Mercedes would recite the misdemeanours of her sons, who, except for Ignacio, would be punished.

Statement of Robert Ramirez, document 20-5 Robert remembered his father having a very short fuse and would take out his temper on himself; he notes an occasion when Julian Snr. had difficulty repairing a sink in the home and hit himself with a hammer, another where he failed to fix a car tyre and kicked the car off its jack, and also that he brandished a gun at his sons, and threatened to blow the head off of one of Robert’s friends.

In a disturbing admission, Robert said that he and his brother Julian were sexually abused by a teacher in their school. In what sounds like a year-long grooming session, the man would come to the house when their parents were still at work; after that, he began taking Robert to his house, where the abuse took place.

Statement of Robert Ramirez, document 20-5 Robert was to spend two years in Huntsville prison for drug offences and three years for stealing suitcases when he was employed by the railroad company. He was also involved in two shootings for which he spent another six months inside.

Statement of Rosario Ramirez, document 20-5. Ignacio

“We were home after school alone until 5 o’clock, and we did whatever we felt like doing. We had water fights in the house, even going as far as spraying each other with the garden hose indoors. One time we even flooded the living room. We also climbed up onto the roof to throw eggs, and whatever else we could find, at each other. Our parents never seemed to realize what was going on. We kids always did our best to hide our activities from our parents. When it got close to 5 o’clock, it was time to start cleaning up”.

Statement of Ignacio Ramirez, document 20-5The medical trauma suffered by Ignacio has been explained in Part One; however, in his statement, Ignacio remembers how, because of it, he was the one who received most of the love and attention from his parents. “I believe that my brothers and sister sometimes acted out just to get attention from our parents”, he says.

His elder brothers, Julian Jnr. and Robert were frequently in trouble with the authorities; he states they were both arrested for drug offences and stole cars.

His father tried to discipline them in the only way he knew, but unsurprisingly, it had no effect. Julian Snr. was once forced to sell a piece of land he had saved up for to pay for legal representation for his two sons. This offsets Robert’s statement, for here we can see a man at the end of his tether, now manoeuvred into a position where he must sell his hard-earned land to foot the bill for the lawyers his sons needed because they could not stay out of trouble.Ignacio, too, remembers the sexual abuse of his brothers:

Statement of Ignacio Ramirez, document 20-5. Richard never admitted that this teacher abused him, but then again, he never admitted anything. It is plausible that he may have been molested as well, although that cannot be substantiated.

Ignacio recalled his cousin, Miguel, and spoke of the atrocities he committed whilst in Vietnam:

“Miguel even claimed that he had in his possession photographs of dead bodies and of women who had been raped and murdered. He claimed he brought these photographs with him when he returned from Vietnam. I never saw the photographs myself; I never wanted to see them. I heard him describe these photographs frequently. Miguel constantly talked about the horrible things he had seen and done in war. On more than one occasion, I had heard Miguel say that he kept his gun in the fridge because he like the feel of cold steel when he killed someone”.

Statement of Ignacio Ramirez, document 20-5.Ignacio tried to talk to his younger brother about the murder of Miguel’s wife, Josefina, but Richard clammed up and refused to talk about it. Richard was, by this time, keeping a lot of things inside.

Of the arguments between Richard and his father, he says:“On more than one occasion, I witnessed loud arguments between Richard and our father: he accused Richard of stealing his tools and selling them for drugs, and he yelled that he needed the tools for work. The arguments never seemed to have any effect on Richard. I witnessed these arguments over and over, Richard never denied it and didn’t seem to care about what our father had to say”.

Statement of Ignacio Ramirez, document 20-5.After moving to Los Angeles, Richard told Ignacio that their brother, Julian Jnr., was teaching him how to steal cars and get properly high.

“He [Julian] asked me why I never taught Richie how to really get high, and he then said that he had had to teach him himself. He also told me that Richard had developed a $500 a day cocaine habit and that Richard was shooting up coke on a regular basis”.

Statement of Ignacio Ramirez, document 20-5.

Despite all this, Richard’s parents, sick with worry, begged their youngest child to return to El Paso and give up the drugs, to no avail; Richard had no intention of returning.

The last time Ignacio saw Richard before his arrest he was a mess: skinny and unclean.Rosa

“After Richie was arrested, I went to visit him in jail in California. As soon as I saw Richie he began to sob uncontrollably. I told Richie, “No ensenes el cobre”, which is something my Dad used to say. It means, literally, “Don’t show the copper”, as in, “Don’t show your true self or feelings”. Now, when I look back on that visit, I wish I had let Richie cry”.

Statement of Rosario Ramirez, document 20-5. Richard apparently took that to heart, and from it, perhaps, came his court room persona.Rosa and Richard were close, with his mother out working long hours; Rosa cared for him. It was to her that he turned for comfort and protection when Julian and Robert were picking on him. Julian and Robert, ten and seven years older than Richard (respectively), took delight in hitting their little brother, calling him “mamma’s boy” and “chiple”, which means spoilt brat in Spanish. As he grew up, Richard also protected Rosa from the same treatment.

Statement of Rosario Ramirez, document 20-5. Rosa noticed the changes that came upon her brother after he began having seizures at around 12 to 13 years of age when he started to self-medicate with marijuana. (His early medical difficulties have already been covered in earlier posts, so please refer HERE for more information).

Regarding the discipline meted out by her father, Rosa says that to outsiders, it may have looked like abuse and that Julian Snr. had received the same treatment from his own father. That was the only way he knew. The punishments were frequent, and “at times, the beatings got out of hand” despite that, it had no effect on the Ramirez boys.

Statement of Patricia Kassfy, childhood friend of Ramirez, document 20-8. In what must have been a painful subject to discuss, Rosa talks of her first husband, Robert Sahs, whom she divorced for his unsavoury activity of going out into the neighbourhood at night, spying on women through their windows. Richard was often taken with his brother-in-law on these outings as a young teenager.

After the divorce, Rosa and Richard (who preferred living with her to his parents) moved into a house together on Corozal Drive in El Paso, where they smoked marijuana every day.

Statement of Gilbert Flores, document 20-8 It was here that Rosa was to meet her second husband, Gilbert Flores, who lived next door; after marriage, Rosa and Gilbert moved out into their own apartment, and Mercedes, Julian Snr and Rosa’s daughter from her first marriage, Jennifer, moved into the house on Corozal. Richard stayed with Rosa and Gilbert frequently, eventually moving in with them. According to Gilbert’s statement, Richard wasn’t getting on with his parents and was sleeping in his car.

Statement of Gilbert Flores, document 20-8. At nineteen, Richard left El Paso for good, spending his time rootless and unanchored between friends in San Francisco and Los Angeles.

After hearing reports about how badly he was doing, Rosa attempted three times to bring him back home to El Paso from California; she says how different he seemed during her visits. The last time she saw him before his arrest, he looked so bad she struggled to recognise him.Finding lawyers for Richard’s defence fell to Rosa; she eventually hired Daniel and Arturo Hernandez. She did so on the advice of the family lawyer, Manuel Barraza, who must have known, as Rosa did not, that these two attorneys were unequal to the job.

The consequences caused a conflict of interest, ensuring Ramirez would never receive a fair trial. These events have been covered fully HERE, HERE and HERE.

To Conclude

Marylin Cornell found critical events and environmental factors permanently and adversely shaped the life of Richard Ramirez, as well as his emotional, cognitive, psychological, neurological and neuropsychological development and functioning.

“His development as an infant, child, and adolescent was severely and adversely affected by poverty, neglect, physical and emotional deprivation and abuse, exposure to violence; family dysfunction and instability; lack of parental supervision, guidance and protection, trauma, and a host of cognitive, emotional, environmental, psychological, neuropsychological, and psychiatric impairments”. (Declarations of Drs. Robert Schneider, Dietrich Blumer, Dale Watson, and Jane Wells, exhibits to the petition.)

Report of Marylin Cornell, document 7-19.No one stepped in, and no one gave him the psychiatric help he needed. He fell through the cracks of society; the cumulative effects of exposure to violence, trauma, and physical and emotional abuse followed him all through his life.

“Petitioner was exposed to multiple traumas and suffered a significant history of physical and psychological trauma, beginning as a young child. He received no treatment or help of any kind for the lengthy pattern of traumatic experiences he had endured. Institutions responsible for Petitioner’s care . . . ignored his disturbed background and consistently failed to provide necessary treatment.”

Report of Marylin Cornell, document 7-19.There are significant lessons to be learned from this.

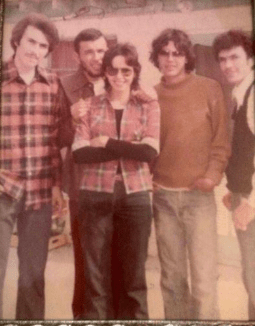

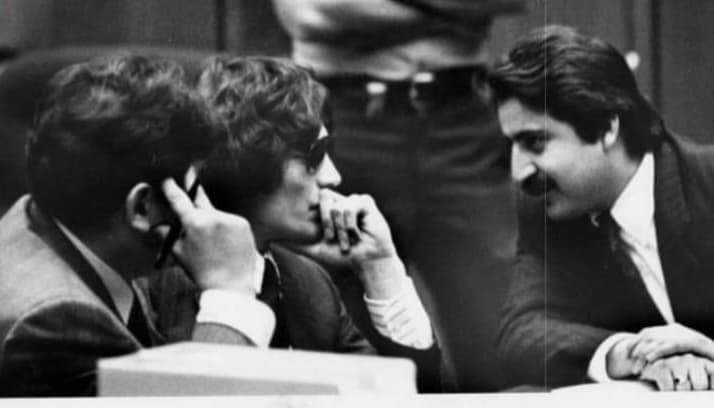

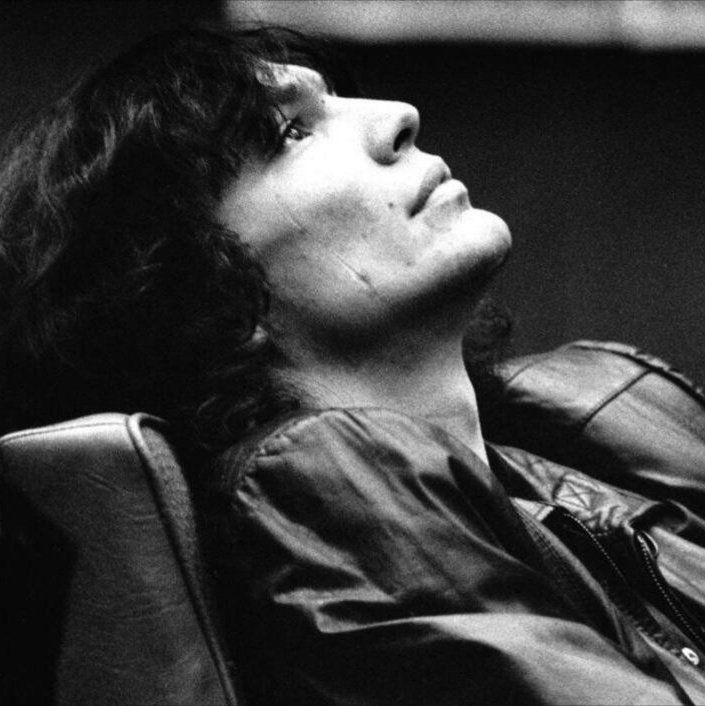

Richard (2nd from the right) and his siblings. Reproduced, with permission, from the Ramirez family collection. ~ Jay ~

-

False Confessions?

“But he literally confessed!”

During the preliminary hearing, Richard Ramirez’s defence team asked Judge Nelson to listen to an hour-long taped police interview from the day he was arrested. Ramirez had repeatedly demanded a lawyer but the police refused and continued questioning him. This violated his Miranda rights. Apparently, Ramirez said some things that could be perceived as incriminating.

Unsurprisingly, Detective Gil Carrillo has subsequently admitted that it was he and Salerno who violated Ramirez’s rights. Carrillo claims that Ramirez suggested what he thought the Night Stalker may have been doing or thinking, which Carrillo interpreted as a third person confession. However, theories about the killer and details of the crimes had been published in the press, and Ramirez, having an interest in true crime, most likely read these.

Although Carrillo admits his interrogation was unconstitutional, he arrogantly claims Judge Nelson was in the wrong and “spoke out of turn.”

“One of the judges said – and that judge is totally wrong – at the preliminary hearing [he] said it was the worst violation he had ever seen after a suspect invoked his constitutional rights – we continued talking to [Ramirez]. Well, what he [Judge Nelson] didn’t realise – he spoke out of turn – was we could not use anything Richard told us in the case-in-chief, nor did we – ‘cause everything he told us initially, we already knew – but we couldn’t use it anyway, unless, if Richard took the stand in his own defence, then we could use it in rebuttal … well, the judge who said it was the worst violation of Miranda… well, this was the worst case of judging I’ve ever seen. He was in violation of –’”

Gil Carrillo on the Matthew Cox podcast.He does not continue. Carrillo knows he was in the wrong. So he does a bad Al Pacino impression to deflect. “You’re out of order!” from the film …And Justice for All. Ironic, as the next line is “The whole trial’s out of order” – which certainly applied to the trial of Richard Ramirez. Ultimately, Judge Nelson said, ‘You know, and I know there’s no evidence anywhere that he confessed to any of the murders.’

Coercion

Carrillo also used some coercive methods, such as threatening to charge Ramirez with child abduction crimes, emotionally blackmailing him about shaming his mother, and asking him if his father sexually abused his sister. This caused Ramirez to suffer a panic attack. This is the point in Carrillo’s routine where he jokes about levitation to deflect from his questionable interrogation techniques.

If Ramirez really did say incriminating things (Nelson believed he did not), they were not admissible for the following reasons:

- Third-person suggestions about the crimes are not direct confessions.

- Ramirez suffered a head injury on the day he was arrested and may have been more prone to strange ramblings, especially if concussed. Traumatic arrests and behaviours symptomatic of trauma invalidate confessions.

- Coercion and manipulation.

- Softening him by placing him in a cell previously inhabited by one of the Hillside Stranglers as a way to make him trust them is also a form of coercion. This patronising tactic might suggest they knew Ramirez was cognitively impaired.

More information can be found in Document 7-4: Exhibit 20, Trauma Related Coerced Confessions, Mary Ann Dutton PhD.

If you are new to this blog, some of Ramirez’s psychiatric reports are discussed here. A person with psychosis could be convinced to believe he or she committed the crime while suffering a psychotic episode. That is not to say this happened to Ramirez, but it is a possiblity. He was brain damaged and struggled with cognitive tests, and yet Carrillo portrays him as legally astute; the “smartest murderer he’s ever interviewed (45:18)” and claims he bragged about having “an ego to fill this whole room (05:15)” He was neither intelligent nor egotistical according to his psychiatrists, of which there were eleven. One, Anne Evans said:

“His ego strength measures as very low, suggesting functioning at a less than competent manner. He also has a very low opinion of himself and compares himself unfavorably to others.”

Declaration Of Anne Evans, Ph.D. Document 16-7.Courtroom swagger was simply an act.

Contradictions

In this podcast, Carrillo himself admits that Ramirez never confessed to being the Night Stalker, yet constantly relates casual conversations with him in which he spilled all. If Ramirez already ‘confessed in the third person’ on tape despite shutting down and asking for a lawyer, when did these other lengthy first-person confessions that a biographer could only dream of take place? Philip Carlo claims Carrillo told him they took place over a week soon after the conviction and conveniently, ‘Ramirez refused to be taped’ (Carlo pg. 406).

Carrillo asks people to believe (and they invariably do) that Ramirez revealed his train of thought during the attacks for example, “Richard said she [Dayle Okazaki] was stupid (40:55)” and revealing where he disposed of weapons (in the San Francisco Bay (1:10:14) and out of a car window* (16:48). He even claims that Ramirez stalked his home, left muddy Stadia prints down his garden path and apparently confessed this to a prison guard. This is not a joke (20:07).

Other Confession Claims

While Carrillo’s ‘confessions’ were thrown out before the trial, other police officers came forward with their own and these were used by the prosecution. One was his supposed confession upon arrest: “It’s me, man.” He could merely have been telling them that he was the person police were looking for – after all, his face was affixed to the dashboards of police patrol cars. They were also asking him for his name.

Other ‘confessions’ are mentioned in Dr Edward Bronson’s declaration in Document 17-2. None of these officers had recorded proof. They are hearsay, but were published in the newspapers as fact, thus prejudicing Ramirez’s trial because potential jurors read them many times:

“Ramirez boasted that he was a “super-criminal” who killed 20 people in California and enjoyed watching them die. Referring to himself, it is alleged that he said, “no one could catch him until he fucked up, he left one fingerprint behind and that’s how they caught him.”

“Enjoyed killing people.”

“I love to kill people. I love watching people die. I would shoot them in the head and then they would wiggle and squirm all over the place, and then just stop or cut them with a knife and watch the face turn real white.”

“I love all that blood.”

“I told one lady one time to give me all her money. She said no. I cut her and pulled her eyes out.”

“[He] waited outside until it was dark, went upstairs, saw two people lying there, and Boom. Boom. I did them in.”

He “could have killed 10 police officers and the next time “no one” will get away.”

“They come up here and they call me a punk … I tell them there is blood behind the Night Stalker”.

– Declaration of Edward Bronson. Document 17-2.

Some of the above quotes came from Sheriff’s Deputy James Ellis, who also claimed Ramirez said, “I would do someone in and then take a camera and set the timer so I could sit them up next to me and take our pictures together.” No such photos were ever found. If these confessions were true, there are many reasons why he may have made them, such as prison bravado to protect himself from hostile guards, or other inmates. Ramirez also suffered from psychosis and temporal lobe disorder and would often spout nonsense. Due to his cognitive disabilities, he often obstructed his own lawyers from helping him.

“Even Mr. Ramirez’s own attempts to pursue a course of strategy in his defense were thwarted by his mental disabilities. Despite having personally sought out a particular appellate attorney in and around 1991 to represent him, Mr. Ramirez would go directly against his advice to not make certain statements to the media which would hurt his defense. He would also inform the appellate attorney that he was “too busy” to meet with him; then Mr. Ramirez would make telephone calls to that attorney’s office which were so disconnected from reality that they reached the point of sounding delusional. The attorney indicated to me that Mr. Ramirez’s mental problems led the attorney to assess him as having the worst judgment of any of the hundreds of defendants he had dealt with.“

Dr Anne Evans, Document 16-7.Other confessions came from his wish to expedite his execution. Officer George Thomas claimed he desired the electric chair and wanted to play Russian roulette, while calling himself “the Stalker.” However, Thomas did not record this, so there is no concrete evidence. Thomas also reported that Ramirez was banging his head repeatedly on the table. This is abnormal behaviour indicative of mental illness and trauma and again, nullifies any confessions.

Ramirez strongly objected to his family being brought to court and during the early stages of proceedings, he veered from insisting he was innocent to wanting to plead guilty to end it all. During this period, he never actually made any admissions. Wanting to plead guilty while in a distraught, irrational state of mind and displaying suicidal ideation cannot be considered a confession and would not be admissible in court. No plea bargains were ever made.

Counsel for the defence were supposed to argue Ramirez’s irrational state of mind and the traumatic nature of his arrest but never did so. They failed to present any evidence of his mental health and brain disorders. They should have objected to the prosecution submitting such evidence – firstly for its unreliability and secondly for the lack of recorded proof.

In 1991, in a calmer and more articulate state, Ramirez maintained his innocence, even telling reporter Mike Watkiss that he was railroaded, although due to his impaired judgement, he would continue to obstruct his own defence.

Philip Carlo

On page 406 of his book, Carlo stated that Ramirez denied ever confessing to Carrillo and Salerno. Even Carlo does not present evidence that Ramirez confessed. A transcript of a recorded interview was published at the back of some editions of his book. There is no confession. If Ramirez really confessed to Philip Carlo, why would he deny confessing to Gil Carrillo? It would hardly matter who he confessed to in the past, if he was confessing for the book. Why would Ramirez ask Carlo “you’re not gonna make me look bad are you?” if he fully confessed to murders on tape? Until new, verified evidence comes to light, the confessions must remain hearsay.

See this post for a follow-up.

-VenningB-

*Carrillo also claims they recovered the guns. This is not true. They recovered one – which was also never proven to be the murder weapon.

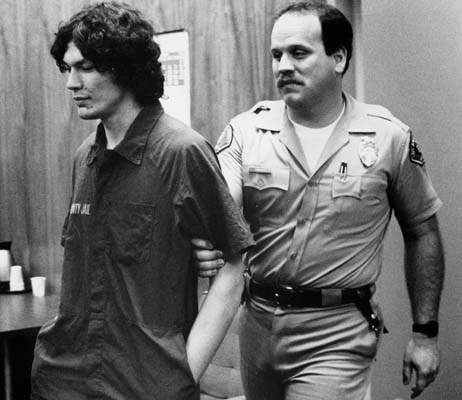

Ramirez in 1991, being interviewed by Mike Watkiss 17th Nov 2023

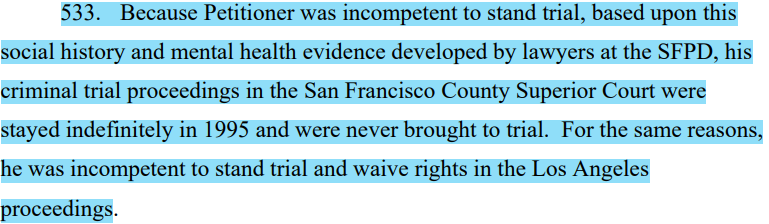

You must be logged in to post a comment.