“The world has been fed many lies about me..”

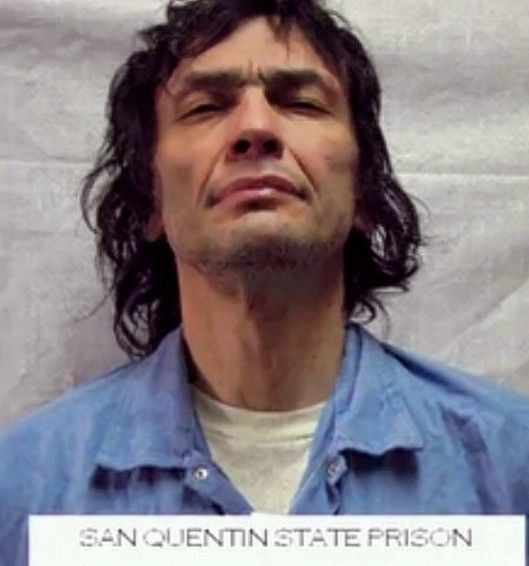

Richard Ramírez

Now available, the book: The Appeal of the Night Stalker: The Railroading of Richard Ramirez.

Welcome to our blog.

This analysis examines the life and trial of Richard Ramirez, also known as The Night Stalker. Our research draws upon a wide range of materials, including evidentiary documentation, eyewitness accounts, crime reports, federal court petitions, expert testimony, medical records, psychiatric evaluations, and other relevant sources as deemed appropriate.

For the first time, this case has been thoroughly deconstructed and re-examined. With authorised access to the Los Angeles case files, our team incorporated these findings to present a comprehensive overview of the case.

The Writ of Habeas Corpus

The literal meaning of habeas corpus is “you should have the body”—that is, the judge or court should (and must) have any person who is being detained brought forward so that the legality of that person’s detention can be assessed. In United States law, habeas corpus ad subjiciendum (the full name of what habeas corpus typically refers to) is also called “the Great Writ,” and it is not about a person’s guilt or innocence, but about whether custody of that person is lawful under the U.S. Constitution. Common grounds for relief under habeas corpus—”relief” in this case being a release from custody—include a conviction based on illegally obtained or falsified evidence; a denial of effective assistance of counsel; or a conviction by a jury that was improperly selected and impanelled.

All of those things can be seen within this writ.

The Writ of Habeas Corpus is not a given right, unlike review on direct appeal, it is not automatic.

What happened was a violation of constitutional rights, under the 5th, 6th, 8th and 14th Amendments.

Demonised, sexualised and monetised.

After all, we are all expendable for a cause.

- ATROCIOUS ATTORNEYS (4)

- “THIS TRIAL IS A JOKE!” (8)

- CONSTITUTIONAL VIOLATIONS (9)

- DEATH ROW (3)

- DEFENCE DISASTER (7)

- INFORMANTS (6)

- IT'S RELEVANT (17)

- LOOSE ENDS (15)

- ORANGE COUNTY (3)

- POOR EVIDENCE (16)

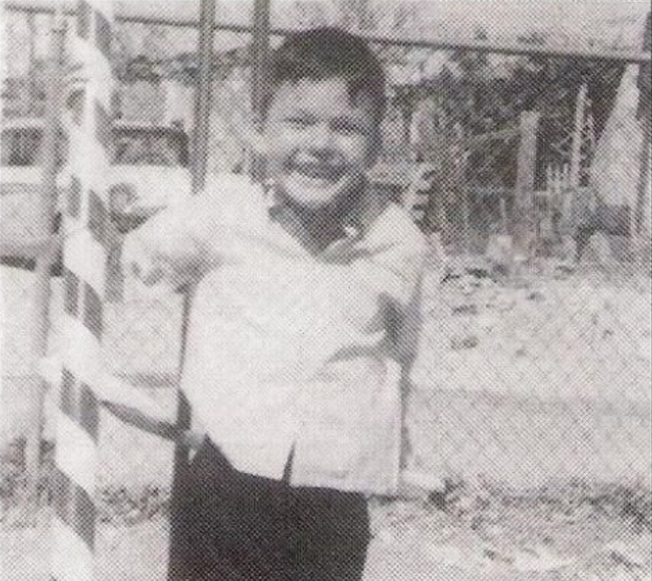

- RICHARD'S BACKGROUND (7)

- SNARK (12)

- THE BOOK (4)

- THE LOS ANGELES CRIMES (22)

- THE PSYCH REPORTS (14)

- THE SAN FRANCISCO CRIMES (5)

- Uncategorized (5)

-

You, the Jury

Questioning

The word “occult” comes from the Latin “occultus”. Ironically, the trial of an infamous occultist and Satanist is the epitome of the meaning of the word itself: clandestine, secret; hidden.

We’ve written many words; a story needed to be told, and we created this place to enable us to do just that.

Here, in this space, we intended to present the defence omitted at Richard Ramirez’s trial in violation of his constitutional rights. Our investigations have taken us down roads we’d rather not travel along, but as we did so, we realised that there was so much hidden we could search for a lifetime and still not see the end of it. Once we’d started, there was no turning back; we followed wherever it led.This was never about proving innocence; that was never the intent or purpose. We wanted to begin a dialogue, allowing this information to be freely discussed and for us to verbalise the rarely asked questions. We asked, and we’re still asking.

We can’t tell you, the reader, what to think; you must come to your own conclusions, as we did.

And so

We’ve said what we came here to say; with 114 articles and supporting documents, we’ve said as much as we can at this point.

This blog will stand as a record of that, and although we will still be here, we intend to only update if we find new information, if we suddenly remember something we haven’t previously covered, or to “tidy up” existing articles and examine any new claims (or expose outrageous lies) that come to light. The site will be maintained, and we’ll be around to answer any comments or questions.

What Next?

We will focus on the book being worked on; we’ve also been invited to participate in a podcast. When we have dates for those, we’ll update you.

The defence rests? Somehow, I sincerely doubt that; ultimately, we’re all “expendable for a cause”.

~ J, V and K ~

-

San Quentin Part 2: Conditions of Death Row

The Death Penalty in America

“The question we need to ask about the death penalty in America is not whether someone deserves to die for a crime. The question is whether we deserve to kill.“

– Bryan Stevenson, founder of Equal Justice Initiative

The United States is the only Western industrialized nation that practices capital punishment, putting it in the company of notorious dictators in countries such as North Korea, Iran, Iraq, China, and Saudi Arabia. The American death penalty system is marred by bias, wrongful convictions, unfair application, and dependence on the defendant’s financial resources and legal representation. It is disproportionately imposed on the poor, uneducated, and people of color. Moreover, it does not effectively deter violent crime, fails to enhance public safety, and is significantly costlier than a life imprisonment without parole sentence. Ultimately, it favors the wealthy and guilty over the poor and innocent.

One in ten prisoners executed in the United States are considered “volunteers,” meaning they have waived key trial or appeal rights to facilitate their execution. This decision is often driven by the appalling conditions they are subjected to on death row for many years before their sentence is carried out.

Since 1978: 1,582 individuals have been executed, while 181 have died from non-execution-related deaths. Richard’s death is included in the non-execution related numbers, as he died from an illness while on death row. Fifteen individuals have had their death sentences carried out. The state of California has carried out 13 of those 15 executions.

California Death Penalty

As of January 2023, 2,463 prisoners were on death row in the United States, with 665 of those being in California. California’s death row is the largest in the Western Hemisphere. An estimate from The National Academy of Sciences concluded that at least four percent of individuals on death row are innocent. California’s death row population is representative of the inherent racism in capital punishment, with Latinos comprising 26% of death row prisoners and 39% of the state’s population.

Does anyone want to guess which county has sentenced the most people to death? That’s right, Los Angeles! Los Angeles County also has the highest number of exoneration cases among all California counties.

East Block was the home of California’s only death row until it was shut down in early 2023. Currently there is a moratorium on the death penalty in California, but it is still legal.

Life on the Row

Death row prisoners are stripped of nearly every freedom while waiting to die. Life is a bleak existence marked by isolation, exclusion from educational and employment programs, restricted visitation, and the ever-looming possibility of execution.

Solitary Confinement: Richard Ramirez spent most of his time alone in a small cell, with limited social interaction and exposure to sunlight, subjected to much more deprivation and harsher conditions than general population inmates.

Limited Time Outside Cells: Richard spent more than 20 hours a day in his cell, only allowed to shower a few times a week, with limited access to exercise and visitations.

Frequent Checks: In California, death row inmates are checked on average 48 times a day. This means Richard had to go through these checks constantly. The checks involve loud noises from keys, voices, and lights, making it hard to sleep without interruption, leading to severe sleep deprivation. Richard spent 24 years on death row (except for the 3 years in the San Francisco County Jail). Imagine how it would feel to be sleep-deprived for over 20 years.

Declining Mental Health: The combination of isolation, limited sunlight, and severe restrictions can lead to a condition known as “death row syndrome.” While it appears Richard had some physical and mental health issues before he was sent to prison, the conditions on death row seem to have exacerbated his illnesses.

Mental Health

Death Row Syndrome: Being confined to death row for an extended period of time can cause deteriorating physical health, agitation, delusions, suicidal tendencies, paranoia, depression, and anxiety. Prisoners wait decades for execution and are subjected to prolonged isolation, which many legal experts have concluded is comparable to torture.

Mental health issues significantly impact death-penalty cases. Individuals with mental illness are more vulnerable to police pressure, less able to assist their attorneys meaningfully, and are typically poor witnesses. Living conditions on death row are deliberately inhospitable, based on the presumption that those subjected to them are not only the most serious offenders but also predatory individuals who pose a continuing danger to others. The American Psychological Association states that the narrative about the danger posed by death row prisoners is unsupported by evidence. However, the evidence demonstrates that a disproportionate number of individuals on death row experience serious mental health disorders that are predictably worsened by the onerous conditions of confinement.

Inside San Quentin

Every death row inmate at San Quentin falls into one of two categories: grade A or grade B. Grade A comprises individuals who mainly abide by prison rules, while grade B includes those who have violated rules, been violent in prison, or have gang affiliations. Those considered “grade B” spend an indefinite period in the Adjustment Center – this includes Richard Ramirez.

From the confines of their cells, prisoners have a view of black bars, a sheet of perforated metal, a railing, and a daunting forty feet of open space before reaching a wall of windows. The cells in East Block measure a mere 48 square feet and stand at a height of 7’7″ – about the size of a walk-in closet.

Any mail sent to prisoners is meticulously examined before being delivered. Adjacent to some of the cell doors are shoulder-high, A-frame metal structures with attached telephones.“Because these guys can’t exit their cells freely, we actually have a phone apparatus on wheels, as we say, and we push it in front of the individual cell. We leave his food port open, and he is allowed to extend his hand out, grab the receiver, and place a call.“

An inmate making a phone call from a cell in East Block (Reuters photography) Nancy Mullane, a reporter for KALW Radio in San Francisco, did a series of interviews with SQ public information officer Sam Robinson about life in the Adjustment Center. The following excerpt is from her 2012 piece titled The Adjustment Center: Where no one wants to go.

“Peering out through security fencing, I see two sorts of recreation yards. Officers direct me out a back door, to a yard of cages. On the far side, a dozen inmates are shooting hoops in one of two group yards, each the size of a basketball court. Guards armed with rifles observe from a walkway above. A little closer are 32 walk alone yards, which are cages the size of small living rooms. Inside each cage a single inmate dressed in white boxer shorts and T-shirt stands or sits alone.

Robinson says these yards are for inmates who either can’t get along with others or have been violent on the group yard. I am hoping to be able to actually see inside one cell in the Adjustment Center. It was one of the conditions I had requested as part of my press access to the facility. But as I press the officers to let me see the inside of just one empty cell, so that I can accurately describe the condition, Robinson says “absolutely not.” You don’t have one empty cell? I ask. “We may have empty cells, but you and I can’t just go down a tier ourselves.” Robinson never lets me see a cell…”Can you envision this being your life every single day, year after year, decade after decade.

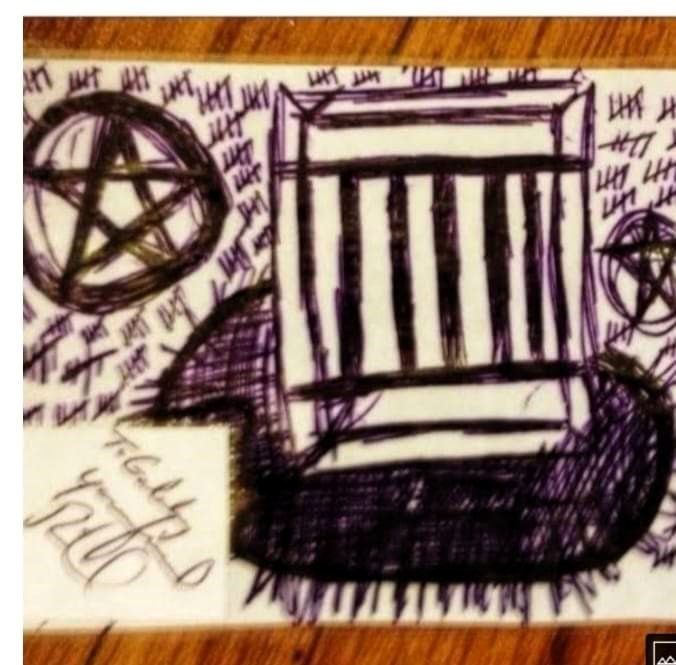

A drawing by Richard marking the days he had been on death row (2013). San Quentin, I hate every inch of you.

You cut me and you scarred me through and through

And I’ll walk out a wiser, weaker man.

Mister Congressman, you can’t understand.

San Quentin, what good do you think you do?

Do you think I’ll be different when you’re through?

You bent my heart and mind, and you warp my soul.

Your stone walls turn my blood a little cold.

San Quentin, may you rot and burn in hell.

May your walls fall, and may I live to tell?

May all the world forget you ever stood?

And may all the world regret you did no good?

San Quentin, I hate every inch of you.”– The song “San Quentin” was recorded by singer Johnny Cash in 1969, at San Quentin State Prison).

Additional Sources:

2008 Federal Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus, Richard Ramirez vs Robert Ayers

The Nightstalker. The Life and Crimes of Richard Ramirez, Philip Carlo, 1996

Time on Death Row | Death Penalty Information Center

California is closing San Quentin’s death row. This is its gruesome history.

Los Angeles County Sheriffs – Past to Present (laalmanac.com)

Wrongful Convictions (eji.org)

The Death Penalty Worldwide – Death Penalty Focus

California Death Penalty Facts – Death Penalty Focus

https://innocenceproject.org/innocence-and-the-death-penalty/

KayCee

Jan 20, 2024

-

San Quentin Part 1: Ramirez’s Life on Death Row

“San Quentin, what good do you think you do?

Do you think I’ll be different when you’re through?

You bent my heart and mind, and you warp my soul.

Your stone walls turn my blood a little cold.”– Johnny Cash “San Quentin“

San Quentin Prison and Richmond Bridge (photo Yahoo News) Founded in 1852, San Quentin State Prison is California’s oldest correctional facility. Located on a peninsula north of San Francisco in Marin County, San Quentin is surrounded by barbed wire fence, tall walls, and watch towers with expert sharpshooters and assault rifles. Yet, it boasts breathtaking views of the San Francisco Bay. San Quentin was initially established to replace a prison ship. Legend has it that on July 14, 1852, Bastille Day in the French Revolution, the ship arrived off the coast of San Francisco with over 40 prisoners. Hence, San Quentin has been known as the “Bastille by the Bay.”

San Quentin has been the site of executions in California since 1893. In 1938, lethal gas became the official method of capital punishment, with prisoners being gassed to death in the sinister, 7½-foot-wide, octagonal, green death chamber. In 1972, the United States Supreme Court struck down the death penalty, declaring that “the imposition and carrying out of the death penalty constitutes cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments,” only to reinstate it in 1976.

Since then, over 1,000 people have been condemned to death in the state of California, including Richard Ramirez. Of that 1000, 13 have been executed, while more than 100 have passed away from other means inside the prison walls.

Due to the lengthy appeals process in the state and the procedural safeguards required by the courts in capital cases, prisoners typically spend over 20 years on death row. They are more likely to die from illnesses, suicide, or be killed by a fellow inmate or prison guard than executed. The vast majority of those sentenced to death have been people of color, and more than one-third of individuals on death row have been diagnosed with severe mental illness.

The Adjustment Center

San Quentin Adjustment Center (National Geography) The Adjustment Center is SQ prison’s maximum-security cell block, also known as “the hole.” This is where prisoners are sent for punishment, and new death row inmates begin their sentences. It is described as a “prison within a prison.”

The Adjustment Center is the harshest of the three death row units at San Quentin. It is severe even compared with other isolation units in the California prison system and most death row units in other states. Residents spend between 21 and 24 hours a day, sometimes for years, inside cells smaller than a standard parking space. There is no natural light (cells do not have windows) or airflow; temperatures fluctuate from hot to cold. Beds consist of a thin mattress on steel or concrete slabs; there are no chairs or desks.Those living in the Adjustment Center are constantly exposed to noise due to the slamming of security gates and cell doors and residents shouting or banging, either in attempts to communicate with one another or as a primal response to their intolerable conditions. The ongoing commotion contributes to chronic sleep deprivation, one of the many adverse health effects of long-term confinement in the Adjustment Center.

Before and after any movement within the Adjustment Center, inmates are routinely strip-searched, often in front of other prisoners and guards, even if they have not come into contact with anyone else during their time out of the cell.

Inmates may only leave their cells for a few reasons:

- Yard visits, in an exercise “cage,” at most three times per week for three hours each.

- Showers (no more than three times per week).

- Medical visits (ONLY if prison guards decide you warrant a trip to medical).

- Rare opportunities for visitors, which occur behind a dirty Plexiglas window through a poor-quality two-way intercom.

“Exercise cages” for Adjustment Center prisoners (Getty Images) Richard Ramirez in “The Hole”

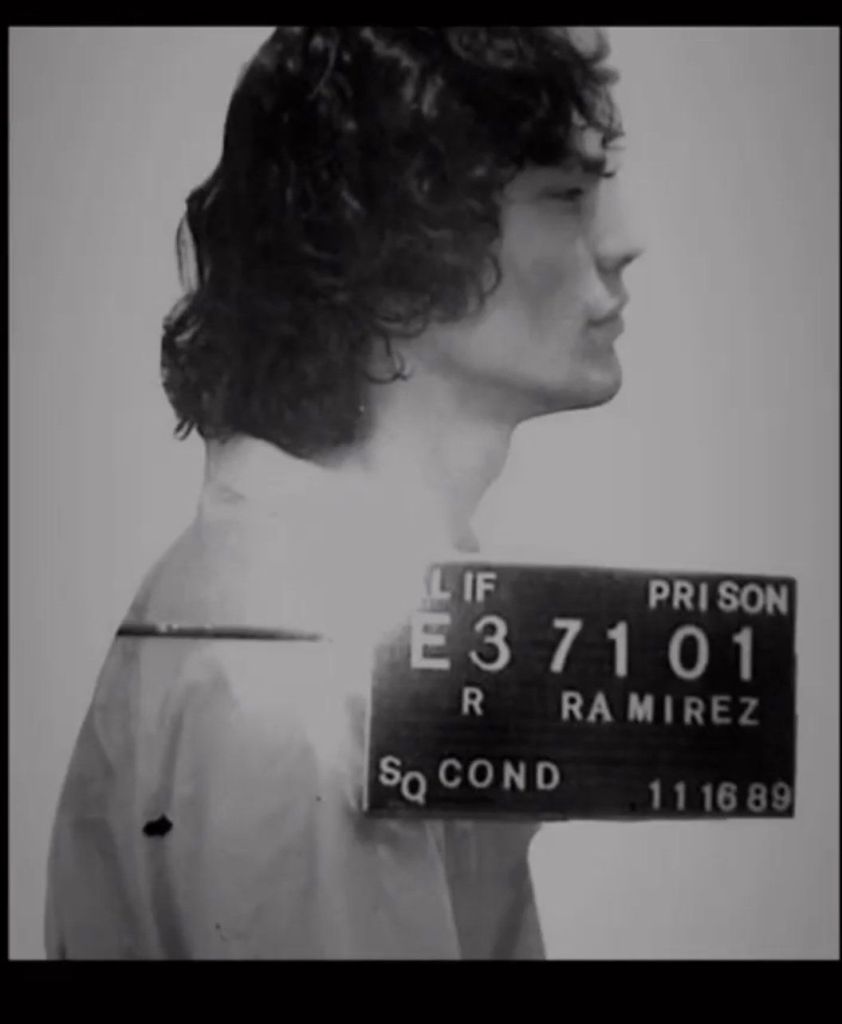

On November 17, 1989, Richard found himself being flown by helicopter from the Los Angeles County Jail to the San Quentin Adjustment Center. The cell was 6’x8′ cell with an aluminum toilet, sink, and bunk bed. Per Philip Carlo’s The Life and Crimes of Richard Ramirez, Richard’s cell was “3AC8” pictured below.

Cell block at San Quentin’s Adjustment Center (Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

Adjustment Center cell at San Quentin (Metroactive Archives) He had no phone access and was only allowed visitation through a Plexiglas window for two hours a week. He remained here until he was transferred to the San Francisco County Jail to await trial for the Pan crimes in February of 1990. He was transferred back to San Quentin on September 21, 1993, although legal proceedings had not concluded in S.F. This is because his “groupies” presented security problems. The following is from the San Francisco Examiner:

“The [San Francisco County] Sheriff’s Department sought the transfer because “the Sheriff’s staff must spend an inordinate amount of resources in an effort to accommodate Ramirez. [He] has numerous visitors … which require an additional deputy to be assigned to the jail’s visiting lobby.”

– San Francisco Examiner, September 3, 1993

Richard was returned to the Adjustment Center. Even though a prisoner was not supposed to be kept there for longer than three months, Richard spent over three years there. His attorney, Michael Burt, had to make repeated requests to prison officials for Richard to be moved to a unit where he could have phone access and increased visitation.

When Richard was transferred, prison guards performed a metal detector scan that revealed Richard allegedly concealed objects inside his body. Consequently, he was escorted to the prison hospital, where an X-ray confirmed the presence of items in his rectum. We can only speculate on the desperation that compelled Richard to resort to such extreme measures – that is if the story is true. Below are two newspaper clippings.

San Francisco Examiner, September 21, 1993

San Francisco Examiner, September 21, 1993 East Block

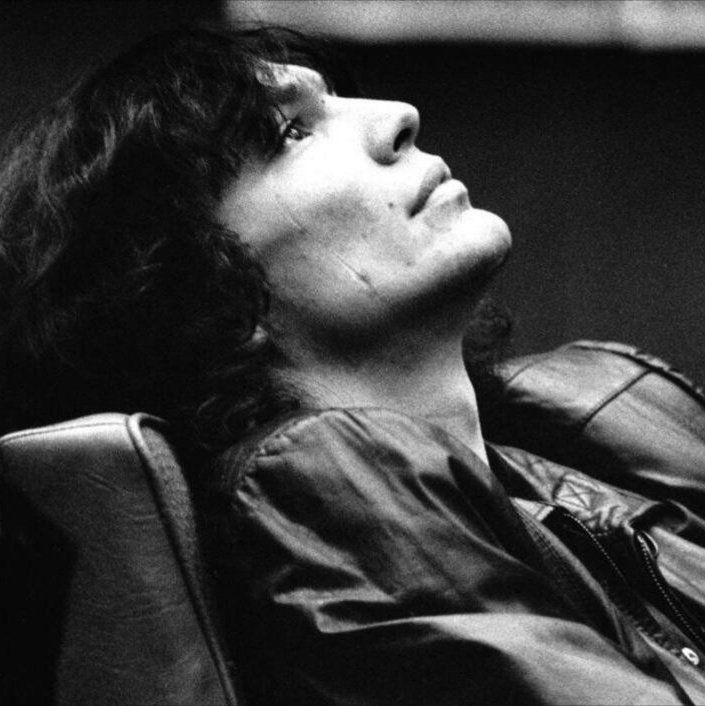

Richard was moved to East Block, the five-tier, main death row cell at San Quentin, in June 1996. This is where he spent the remaining 17 years of his life. There are few sources available detailing what life was like for Richard as a condemned prisoner. In his interview with Philip Carlo, Richard said his cell in East block was even smaller than the one he had occupied at the Adjustment Center.

East Block (AJ Hardy) Although Carlo used creative license in writing his book, he did include excerpts from his interviews with Richard in the special update of the tenth-anniversary edition. Below is a portion of an interview conducted by Carlo while Ramirez was incarcerated in East Block:

“Carlo: What’s it like living on death row, Richard?”

Ramirez: It is monotonous, it is boring … because it is so boring it breeds tension. There’s a lot of tension in here. Frustration … you never get used to it. I myself only tolerate it. I have acquaintances – no friends. Every day, it’s the same routine. The walls close in on you.

Carlo: How many hours a day are you actually in your cell?

Ramirez: Well, like I told you, the program they have me on now – which is maximum security – I got out sixteen hours a week.

Carlo: So are you locked up twenty-four hours a day?

Ramirez: On some days, some days, yeah. I go outside for about five hours on Tuesday, I got out five hours on Friday and I go out five hours on Sunday.

Carlo: How’s the food on death row?

Ramirez: Edible.

Carlo: Are you able to eat with the prisoners on death row or do you –

Ramirez: They feed us in our cages.Ramirez, in his interview with Carlo, gave his opinion on how unnatural it felt to be on death row.

“Sometimes it feels very strange to wake up and be in that cage, in that cell and … I don’t think man was meant to be locked up in such a way. Maybe they had a thing going on in the Western days [old West] where they would just lynch the guy right off the bat, see what I’m saying? But they don’t do it now like that.”

Richard theorized on the reasons the death penalty appeals to people and who is more likely to end up on it:

“Ramirez: As far as the death penalty is concerned, I think it is a power against the powerless. There are not many millionaires on death row … The death penalty is … to me … is not a very dignified way.

Carlo: Do you think that the government does not have the right to take a life, or do you feel that in certain crimes –

Ramirez: Well, they’re doing it for the victims. If the relatives of the victims want the killer’s blood … uh … I think one of the relatives should pull the plug, the switch. But they leave it up to the state and … that is something to look at.”Death Row Romeo

In a Current Affairs episode aired in 1991, Richard was labeled the “Death Row Romeo” due to his reputation with “groupies.” How does one become a “Romeo” when locked behind iron bars, under the watchful eye of security guards 24 hours a day?

Ramirez downplayed his “sex symbol” status as shown in this San Francisco Examiner article, dated August 3, 1991. It claims that eight to 10 women arrive every week. Other times, there were so many that they had to be turned away.

Richard was modest about why women were visiting him. It says:

“He said reports on the number of his female visitors were exaggerated. “The ones who do visit me are sympathetic.”“

While many women wrote letters to Richard and visited him, that was the extent of his relationship with most of them, as he was not allowed physical contact visits, except for Night Stalker trial juror, “Cupcake” Cindy Haden, and Doreen Lioy – who later married Richard.

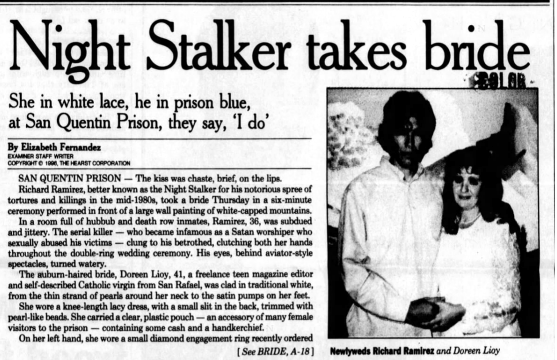

Haden was only allowed physical contact visits after becoming a private investigator and alleged that she wanted to help with Richard’s case. Doreen wasn’t allowed contact visits until Richard was moved to East Block in 1996, four months before the “Death Row” wedding, on October 3, 1996. Below are two newspaper clippings about his marriage.

San Francisco Examiner, October 4, 1996

San Francisco Examiner, October 4, 1996 Carlo’s interview concludes with Richard’s hopes for his future:

“He says he was railroaded and has hopes in the appeal. He has changed much in the eleven years since August of 1985. He’s gained thirty-five pounds and he’s mellowed out … But by no means has he adjusted to the reality of his existence. He does not like being in the adjustment centre, saying it’s cruel and unusual punishment, and he often paces his cell like a caged panther … Richard believes he will win the appeal, win at a new trial, and be set free”

Additional Sources

2008 Federal Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus, Richard Ramirez vs. Robert Ayers

Night Stalker. The Life and Crimes of Richard Ramirez, Philip Carlo, 1996

https://www.cdcr.ca.gov/facility-locator/sq/

A look at the hard life inside San Quentin’s Death Row (sfgate.com)

What it’s like on California’s Death Row | KCRW

KayCee

Jan 14, 2024

-

Child Abductions: Not A Night Stalker Thing

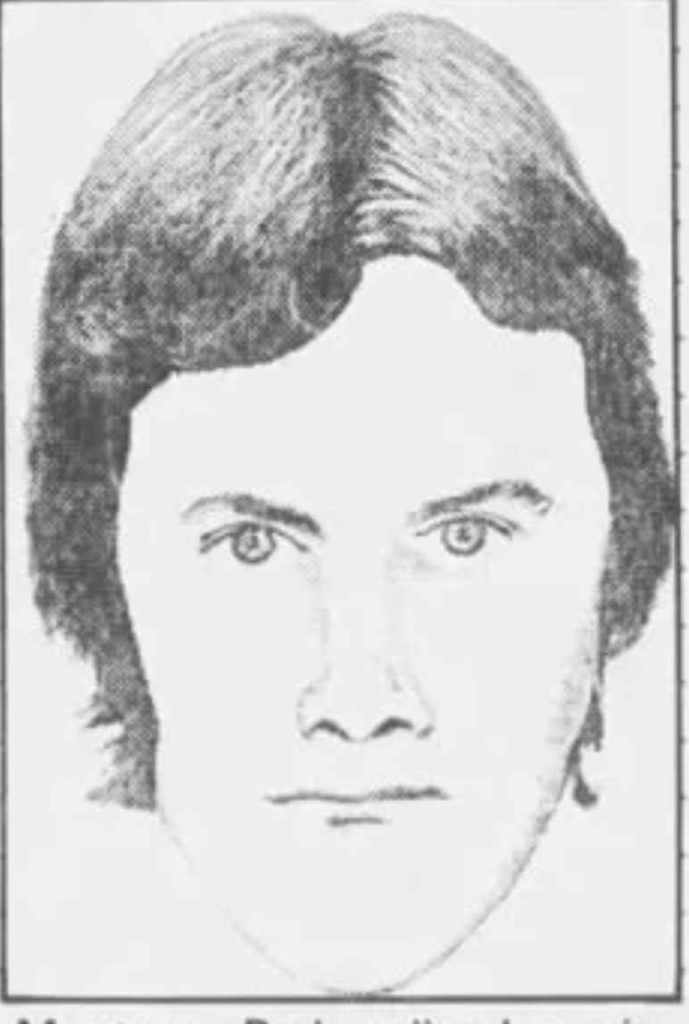

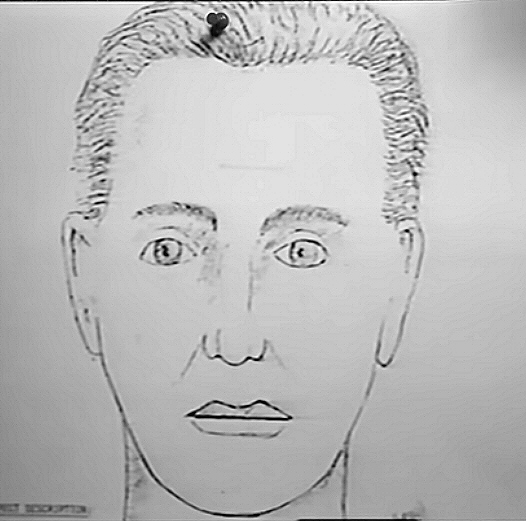

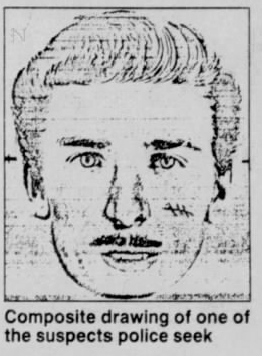

On this blog, we have already established that there is no evidence that Richard Ramirez was abducting children, as mentioned in this general outline of the whole case. Primarily, because it is impossible for anyone to shapeshift in the way Ramirez supposedly did. When DNA supposedly tied Ramirez to the brutal stabbing of nine-year-old Mei “Linda” Leung, it appeared to vindicate the allegation that Ramirez harmed children, although that case is not as clear cut as the public have been led to believe either. We covered the Leung case here. Below: the February-March 1985 child abductor/s from the Los Angeles Times and the Netflix documentary (centre).

While the child cases never went to trial “because the prosecution wanted to protect the children”, they (and adult victims) were being coached to pick Suspect Number 2 at the line-up, also covered in ‘Shapeshifter’ and this post on Anastasia Hronas in which a detective admits he told her what she saw. If those child abduction cases had gone to trial, it could have damaged the credibility of the rest of the claims, because it would soon be discovered that the original suspect – or one of them – was a blonde man.

We say one of them because there were many of these crimes happening in Los Angeles, Los Angeles County and Orange County. This was not some new phenomenon that occurred at the same time the “Night Stalker” was supposedly at large and stopped abruptly in September 1985. It continued in the same manner after Ramirez was captured. Some of the perpetrators might even be the same kidnapper as in 1985. The following is by no means an exhaustive list – many more can be found in the news archives. While child abduction numbers where greatly exaggerated as part of a 1980s moral panic, there were enough to make parents worry. Sometimes, these kidnappers killed.

Pasadena, L.A. County: In December 1986, Phoebe Ho of South Pasadena was abducted on her way to school and her body was found dumped in Riverside County. Warren James Bland, charged with her murder, also had a penchant for stealing Toyota Corollas, a car model constantly linked to Richard Ramirez.

Placentia, Orange County: Another crime thought to have been committed by Bland was that of Wendy Osborn, aged 14, who was abucted in the same way, from Placentia in 1986. Her body was found dumped in Chino Hills, San Bernardino County. However, in 1995, DNA proved the killer was Raymond Barthlett. Barthlett was already in prison for a similar crime in 1988, in which the girl survived. The survivor, Kelly St John, went on to create a documentary about Osborn’s murder.

Tustin, Orange County: in June 1987, a father beat an intruder unconscious after he tried to drag his daughter, nine, out of their house at 1:45am. This abductor was Paul Edward Kumbartzky. He was 5’8”, slim to medium build with brown hair and blue eyes. The police were also looking for another kidnapper in Tustin at the same time, where Patricia Lopez, nine, was abducted and killed by a stocky Latino suspect with a moustache. In 2007, DNA discovered the real killer was her brother, who was 21/22 in 1987. He was charged with her murder but died before the trial.

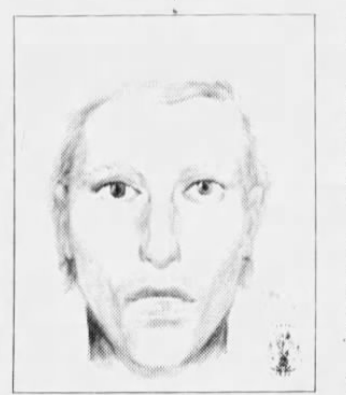

Duarte, Los Angeles County: on 13th November 1989, a man attempted to kidnap two girls aged seven and eight outside Royal Oaks Elementary School. The two girls fled and told police the man was six feet tall, white, with black curly hair. This crime is very similar to the ones connected with Richard Ramirez, that occurred outside schools situated on Donna Way, Montebello (March 1985). However, back then, a child abductee (and an adult witness to another failed kidnapping) both mentioned a blonde man of medium height and build. Ironically this Duarte kidnapper’s appearance is closer to Ramirez’s than the suspect in the crimes he was accused of.

The following day, 14th November 1989, a nine-year-old was cycling home from Andres Duarte Elementary School when a man knocked her off the bike with his car and ordered her inside. The girl climbed back onto her bike and cycled away. However, this sounds like a different man from before. He was white, in his 20s with brown hair, brown eyes, a moustache and heavy set. He had a cut with stitches on his left cheek. He drove a red four-door car. This is his composite sketch.

Another article on the Duarte abductions suggested that this was a rare problem – a school district superintendent said this was an unusual crime; that he had never dealt with anything like it. While it was not his area, surely he remembered the kidnappings attributed to the Night Stalker just four years earlier? Duarte is close to Arcadia, where Anastasia Hronas was from.

La Verne, L.A. County: The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department did not think the above Duarte cases were related (rightly), nor did they believe any of the perpetrators committed yet another abduction on 12th November 1989. In this La Verne case, a six-year-old girl was abducted, sexually abused and released by her captor in a local park. It is curious that in 1985, detectives were obsessed with linking Ramirez to six abductions where the multiple suspects looked nothing like him, yet four years later, the LASD insist that three similar cases over a three-day period were definitely not the same man. Again, a lieutenant from the LASD stated that, “None of us can remember this ever happening in the history of the city.” He probably specifically meant La Verne (in L.A. County, the districts are separate ‘cities’), but surely he remembered the abductions of 1985, that took place in Montebello, Eagle Rock, Monterey Park, Highland Park, Rosemead and Arcadia?

Interestingly, this suspect was white, about 30-years-old, medium build, medium height, with light brown or blonde hair. Although this man had a moustache, he is very close in appearance to the man sought for the March 1985 abductions Ramirez was accused of. He could also be the man with the cut on his face from the 14th November Duarte incident (although he was “heavy-set”).

South Bay, L.A. County: in September 1989, there were seven attempts to kidnap nine children in Redondo Beach, Hawthorne and Manhattan Beach. The suspect was either white or Latino and in his 30s. His complexion was tanned and he sported a dark moustache and hair. He sometimes wore sunglasses. The children said he either drove a blue pickup truck or a Pontiac or a station wagon. Had this been four years earlier, Ramirez might have been accused, for he once owned a Pontiac and is portrayed as committing crimes in station wagons.

South Central Los Angeles: In April 1991, a man was committing identical crimes in South Central Los Angeles, where five girls aged between nine and 14 were snatched as they walked to school, molested and abandoned. This was a black suspect (Kevin Shovor Samuel), so obviously was not the same men from Los Angeles County, but it demonstrates that these are not rare or unusual crimes. It happens in inner city areas just as much as it does in suburbia.

Costa Mesa, Orange County: in April 1991, an eight-year-old girl was walking to school when a man tried to drag her into his car. The man released his grip when some passers-by witnessed and screamed. Disturbingly, there were other children inside his car. He was about 40, 5’10” with short brown hair and a moustache. He had a red and green rose tattoo on his hand.

Seal Beach/Huntington Beach, Orange County: August 1991. Glen Scott Simons, 25, was arrested of trying to drag a 12-year-old girl into his car. Ramirez was also accused of trying to snatch two 12-year-olds, particularly one in Highland Park, allegedly just before the traffic offence. Similar to the Highland Park case, thankfully, this girl broke free. A month earlier, there had been a similar incident in which a man tried to force a 14-year-old into his van and pointed a gun at her.

San Gabriel Valley: in 1992, back in the general area of the 1985 Night Stalker crimes, another child abductor was on the loose and driving a Toyota pickup truck. A four-year-old girl was snatched from a street in San Gabriel on 27th May. A few days later, a five-year-old was taken in Monrovia and escaped from the truck when the driver stopped at a red light. This suspect was thought to be involved in a third incident with a San Pedro child (not in the Valley), also aged five. The suspect was 25-30 years old, medium build and about 5’8”. He had slicked back hair, possibly in a ponytail. Just days later, detectives arrested Steven Scott Rivers, aged 30, based on a composite sketch shown on the news (sadly not included in newspaper articles).

With these cases, Detective Darren Perrine said he looked at San Gabriel, Rosemead and Pasadena sex offender lists and created a shortlist of which Rivers was the most likely, based on a drawing. In Pasadena alone, there were 1,062 sex offenders. So why is it that this register was not checked when the 1985 abductions were happening? Why was it immediately thought to be the ‘serial killer’ that Detective Carrillo was hoping to catch? Was it just the presence of an Avia print at one dumping scene that took police way off track? In any case, those children have never had justice, because they have gone down in history as Richard Ramirez crimes, with no hope of reinvestigation.

A map of the many abduction cases -VenningB-

-

And Justice for All

*images may need desktop viewing for clarity*

“After a recess, in another hearing held in the court’s chambers which was held outside of the presence of Petitioner, the court and the parties discussed courtroom security. Trial counsel was concerned that there had been no screening of the members of the public which were coming to watch the trial. Trial counsel was concerned because the defense attorneys had received death threats”.

Petition of Habeas Corpus, page 578

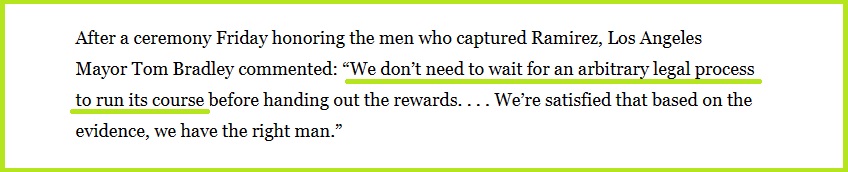

The above quote is taken from the main document of the 2008 petition; it is regarding a hearing concerning security within the courtroom; death threats had been made towards the defence attorneys by members of the public who felt that Ramirez should not receive legal representation. These same people were probably of the same opinion as Mayor Tom Bradley, who declared to the press that a trial wasn’t needed as he was guilty, and he knew that based on the evidence he had seen.

LA Times, 10th September 1985 This statement, made after his award ceremony honouring the “Hubbard Street Heroes”, is one of many made to the media before the arraignment. One can imagine the mayor, followed by an array of torch and pitchfork-waving citizens, hustling Ramirez up to the door of the gas chamber; no trial needed. What a strange understanding of “liberty and justice for all”. Death threats for simply trying to do their job?

Mayor Bradley and the people of Los Angeles, collectively suffering from memory loss, forgot that under the 6th Amendment, every defendant is entitled to a fair trial and the effective assistance of counsel.

This is part four in a series of posts about the defence.

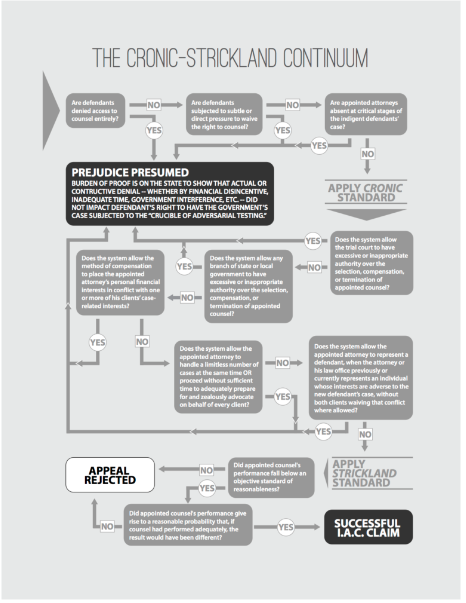

Lawyer Roulette – Cronic and Strickland, a Brief overview

The petition repeats two words: “Cronic” and “Strickland”.

So what do they mean? In brief, Cronic and Strickland are two Supreme Court cases that decide the two-pronged testing used to determine the effectiveness of counsel, principally for indigent defendants.

Strickland looks back at a trial where the outcome has already been determined and asks if the attorneys provided effective assistance of counsel and if incompetence prejudiced the outcome.Cronic looks forward at the start of the proceedings to try and assess if certain factors are present or absent, and if so, the court should assume that ineffective assistance of counsel will occur. (Source: 6ac.org)

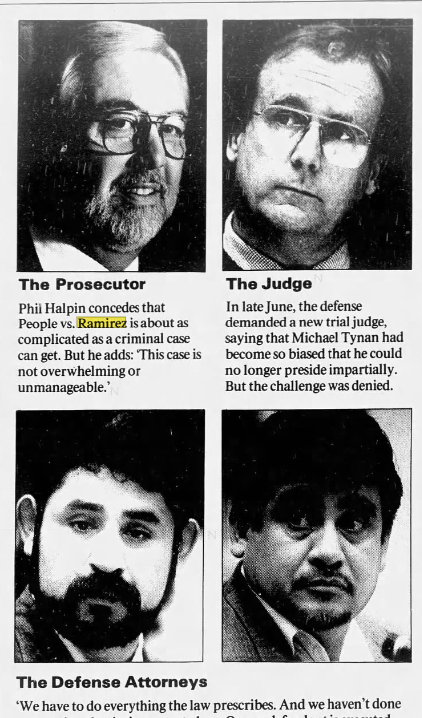

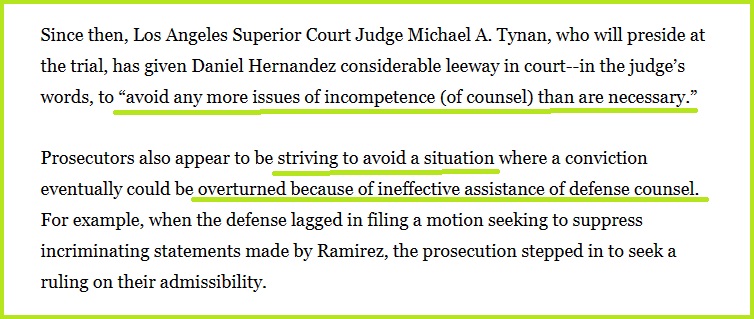

Prosecutor Halpin, well aware of the implications, had to remind Richard’s attorneys how to do their job more than once.

L.A Times, January 6th, 1989. “The overarching principle in Cronic is that the process must be a “fair fight.” Cronic notes that the “fair fight” standard does not necessitate one-for-one parity between the prosecution and the defence. Rather, the adversarial process requires states to ensure that both functions have the necessary resources at a level their respective roles demand.“

As the U.S. Supreme Court notes: “While a criminal trial is not a game in which the participants are expected to enter the ring with a near match in skills, neither is it a sacrifice of unarmed prisoners to gladiators.”

“Cronic’s necessity of a fair fight requires that the defence attorney put the prosecution’s case to the “crucible of meaningful adversarial testing.” A constructive denial of counsel occurs if a defence attorney is incapable of challenging the state’s case or barred from doing so because of a structural impediment.”

Source: 6ac.org

Image source: 6ac.org

The Judicial Lottery

On January 6th, 1987, the court gave the following soliloquy in a closed session. This was exactly two years before the L.A. Times news report above.

“Now, I am calling this hearing, Mr. Ramirez, to tell you that I reluctantly have to tell you that in my opinion your lawyers are incompetent.

Now, I have had this case for six months, and I must say that I am convinced that your lawyers are nice guys, good company, maybe good fellows to spend an evening with. I am also convinced that they are dedicated to your defense emotionally. But I must tell you that, in my opinion, they are not competent to handle your case.

I don’t think that they have sufficient experience in the law. I don’t think that they have the staffing, if you will, or whatever, to do the job…I am telling you now…I don’t think they know the law well enough, I don’t think they know the rules of evidence well enough, they are not ready to present the evidence and push it through….I am just telling you this because I have no personal axe to grind at all, I simply want to see that whatever happens in this case is done right and you get your rights protected, that whatever conclusion is reached is right. And I am telling you now that your rights are not being protected.”

Habeas Corpus, page 204 – Judge Dion Morrow – Prosecutor Halpin moved to have him taken off the case.When the Hernandezes initially requested to substitute themselves in place of Joseph Gallegos, Arturo assured the court that they were fully funded and that paying for the defence wouldn’t be a problem. “All the resources are there…no matter how long it takes” (from a hearing on October 22nd, 1985). He failed to inform that court that there had been no money incoming from the family and that they hoped to be paid from the proceeds of any film or book deal obtained. When the hoped-for agreement didn’t materialise, as Ramirez refused to sign a contract, Arturo took on extra cases, alongside Richard’s trial, for the next four years.

L.A Times, July 17th, 1988 Even before the trial began, the lack of funding available to the defence was causing delays; Arturo explained to the court that as “Mr Ramirez is an indigent defendant he doesn’t have the means or resources , as the People do, to maintain as pace that is required by the People”. (from a recorded transcript 906-907)

The court, inpatient and annoyed, chastised the Hernandezes for their constant tardiness and for raising financial concerns for their delays. They had, after all, assured the court that their defence was fully funded during the hearing for the substitution of counsel.

“Financial concerns are not reason really (sic) to continue this case. You owe [Mr. Ramirez] a duty of at least warm zeal on this case, and of course, as officers of the court—this court, owe prompt attention to this case.”

(Id. at 3007.) Habeas Corpus, page 230Daniel Hernandez’s Health

By May of 1987, the Hernandezes closed their local offices, telling the court in a sealed recorded transcript that they were “broke”, and moved back to their office in San Jose. The court appointed another attorney, Michael Carney, to help file motions. The situation didn’t improve; Daniel and Arturo were in San Jose working on other cases and needed to communicate with Carney, which they didn’t. These other cases, worked concurrently with the Night Stalker trial, meant that none of their clients were getting the defence they were entitled to.

In January 1989, with the trial just beginning, Daniel Hernandez tried to force the court into giving him funding (this would only be allowed if the court agreed to appoint him, which they refused to do), claiming that his client’s defence would suffer without additional funding.

“Mr. Hernandez, when you tell the court that if you don’t get appointed you are going to withdraw, or if you don’t get appointed you are going to do less than diligent work on this case, as you appear to state in these motions, that is frightening to me because that is extortion. And I will be honest with you, this court is not going to be extorted.”

(Judge Tynan. Sealed January 20th, 1989, 140A RT 16005.)Judge Tynan accused Daniel Hernandez of lying to Judge Soper about their financial situation at the time of the substitution in October 1985. Extortion failing, Daniel tried another tactic in that he was too ill with stress to function correctly as an attorney. One might question his ability as an attorney in the first place, with or without stress.

Letter to the court from Daniel Hernandez’s doctor, document 7 -4. “Perhaps realizing its deficient performance, counsel admitted, “I am under some medication, I am not making a lot of sense sometimes, and I advise the court I have been under medication for the last two weeks. Let the record be clear that if you are having some problems, it is perhaps because of my medication.” (16 RT 741.) A reasonable justification for abridging Petitioner’s right to counsel does not include being medicated.”

Habeas Corpus, page 314, a pithy response from the Habeas lawyers.In June 89, Daniel again blamed his lack of funds for not presenting any defence witnesses, witnesses like Eva Castillo (who strangely disappeared) and others who should have been investigated. He asked for a delay, which was (unsurprisingly) denied. This was the exchange:

“You are going to be in the same boat, aren’t you? You are dead broke now. You are not eating.”

“I’ve been going without anything for myself for four years and now I have to eat my pride again and say I’m broke, and even then, you stuff it down my throat.” (Sealed June 26th, 1989 hearing, 199A RT 23267). Habeas Corpus Page 233.

The lack of funding was a direct result of their agreement with the Ramirez family; this “conflict of interest” was the price paid by Richard for their unethical, third-party contract arranged by his family. No money was raised, and Arturo Hernandez claimed that the Ramirez family’s inability to pay would cause them “to give less than adequate representation and render ineffective assistance of counsel to our client, because we have to work and try to survive and maintain some sort of practice.” (Sealed September 29th, 1987, 33C RT 2358

Arturo Hernandez appeared to be threatening the court with an inadequate performance unless they were court-appointed. The reasons why the court refused to appoint them, unlike Ray Clark, whom they did appoint, are explained HERE.

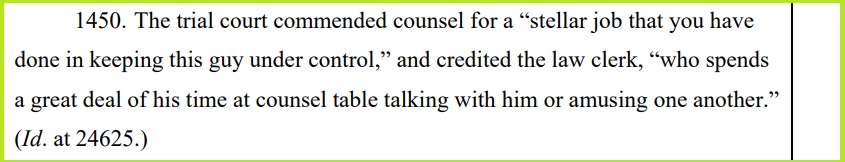

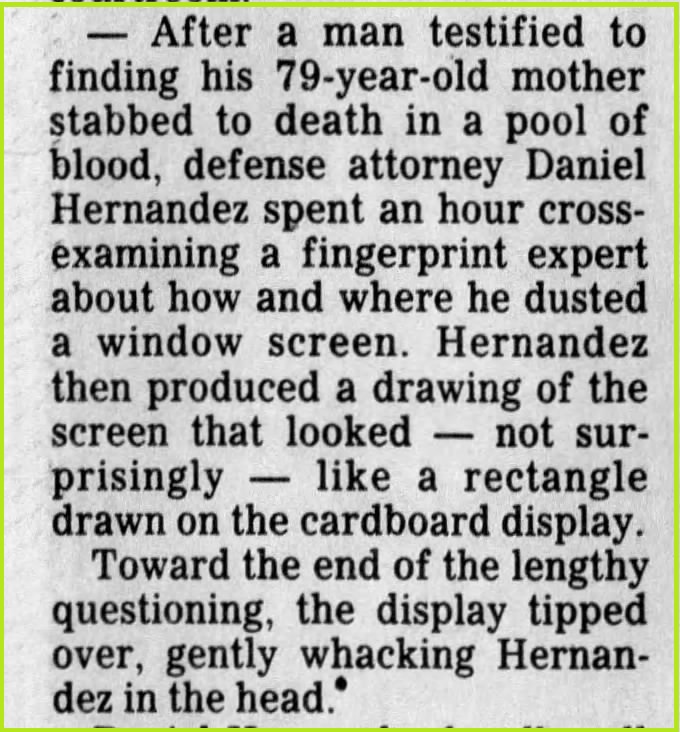

Ramirez was stuck in the middle of this battle of wills, unable and unwilling to concentrate. Tynan thanked Richard Salinas, Daniel’s assistant, for keeping him amused, like a child. I am surprised they didn’t supply crayons and a colouring book to complete the gesture.

Habeas Corpus, page 574.

Timeline of Incompetence

Lists can be tedious. However, this list is essential, demonstrating how badly the defence handled the case.

- From September 26th 1988 to January 23rd 1989, Daniel Hernandez conducted voir dire without the assistance of co-counsel Arturo Hernandez. Voir dire being the process where potential jurors are vetted for suitability for serving and, more importantly, weeded out for biases.

- On October 3rd, 1988, the trial court sent a letter to Arturo Hernandez regarding his absence from the trial.

- On October 18th, 1988, the court issued a body attachment for Arturo Hernandez and ordered it held until October 24th, 1988. A body attachment is a warrant issued by a judge authorising law enforcement to arrest someone and bring them to court.

- October 25th, 1988, Arturo Hernandez appeared in court to explain his absence from trial and requested to be relieved from Richard’s defence, stating he could not communicate with him.

- February 21st 1989, Daniel Hernandez did not appear at trial due to illness during the prosecution’s case-in-chief. This is especially damning; Arturo was also absent, meaning neither of them were present during this crucial moment.

- February 24th 1989, the trial court ordered Daniel Hernandez to inform the court of his medical condition. He failed to do so.

- Neither counsel appeared in court on February 21st and February 27th, 1989; instead, law clerk Richard Salinas appeared on Richard’s behalf.

- On February 27th, 1989, the court continued trial to March 6th, 1989.

- March 1st, 1989, a hearing was held concerning trial counsel Daniel Hernandez’s health. The court determined that there was no legal cause to delay the trial.

- March 6th, 1989: Ray Clark was appointed as co-counsel. It’s far too late for him to be of much use.

- July 13th 1989, prosecutions closing argument, neither Daniel nor Arturo Hernandez were present. Arturo didn’t turn up, and Daniel didn’t bother to return from lunch, causing the jury to be excused for the rest of the day. “As you can see..Hernandez isn’t with us this afternoon. Frankly, we don’t know where he is”. Frankly, that’s just not good enough.

- July 14th, 1989, the court ordered Daniel Hernandez to be present at all hearings and Arturo Hernandez to present himself in court on July 17th.

- July 17th 1989, Arturo Hernandez failed to attend court for the closing argument of the guilt phase.

- August 18th 1989, Arturo Hernandez was found in contempt of court and fined. He had told the court he was in Mexico attending his brother’s funeral; he was in Europe on honeymoon. Trial court found him to have abandoned Ramirez.

- September 14th 1989, Arturo Hernandez was again found in contempt for not paying his fine. The court issues another arrest warrant, and bail is set for $5000, but withdraws the accusation of abandonment.

- September 15th 1989, Arturo Hernandez contacts the court.

- September 18th, 1989, Arturo Hernandez paid a cheque for $100. The court sentences him to 24 days in jail or pay a $2400 fine. He’s jailed for one day for late payment of a $100 contempt of court fine.

- September 19th 1989, Arturo Hernandez pays the $2400 fine.

- September 20th 1989, Richard is found guilty.

A notification of court proceedings against Arturo Hernandez with a list of his fines/sentence for being in contempt. This was one of documents we found during our research at the LA archives in October. “Counsel’s lack of qualifications, failures to appear, and incompetence were obvious to the trial judge throughout the proceedings. Furthermore, it is clear that counsel’s deficits endangered the fairness of the proceedings, and diminished the integrity of the legal profession. The trial court erred in allowing Petitioner to stand trial on capital charges with such ineffective representation.”

Habeas Corpus, page 245

In-Court Display Disaster

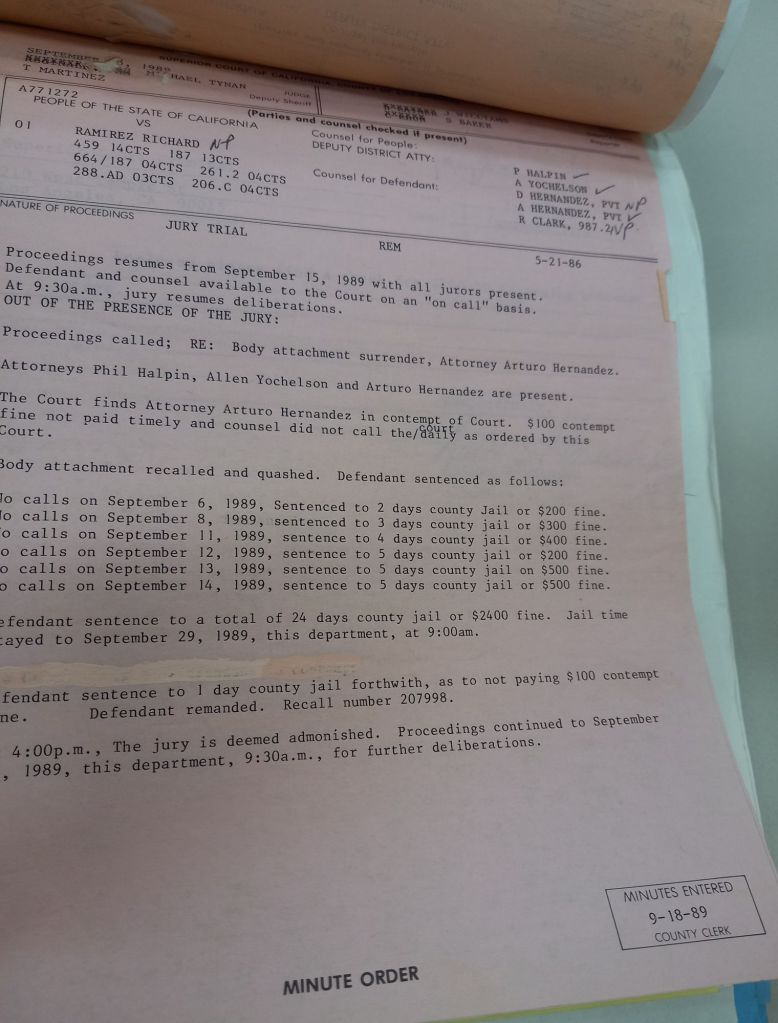

On occasion, Daniel Hernandez made a valiant attempt to defend Ramirez; to say otherwise would be unfair; although lacking technique and the critical skills so desperately needed, his attempts often looked faintly ridiculous.

During the cross-examination of the prosecution’s fingerprint expert in the Vincow incident, Daniel spent a couple of hours trying to get the examiner to demonstrate exactly where the alleged fingerprints were on the window screen. He even brought his own in-court display, a piece of cardboard that finally fell on top of him.

The newspaper reporters had this to say:

Daniel gets smacked by his display, Monrovia News Post, 20th April, 1986. An LAPD fingerprint expert, Darnel Carter, said that the prints found on the screen at the Glassell Park apartment matched those of a suspect, but the name had not been released. However, the police said the prints belonged to Ramirez, so we hear no more about this.

Monrovia News Post, March 9th, 1986. According to news reports, Hernandez TWICE asked to examine the fingerprint evidence, but Judge Nelson denied his request. Daniel Hernandez was correct when he told reporters that fingerprint evidence is not infallible. Why Nelson refused his request is a question that has never been answered, and refusing the defence a better look at fingerprints seems a common trait; the U.S. Government later refused Ron Smith (fingerprint expert for the defence, post-conviction) a look at them as well.

Those fingerprints were never independently verified. In this instance, we should cut Daniel some slack. Just a little.

Dodgy Diagrams

As previously discussed in an earlier post, the defence didn’t retain an expert witness to challenge the prosecution’s misleading shoeprint evidence. Daniel rallied to the task with another in-court display, which purportedly showed all the incidents where the Avia shoeprints were discovered. He managed to get it wrong and included the Kneiding incident.

No shoeprints were found at the Kneiding crime scene, which the defence should have known, and getting it so badly wrong is appalling. In his closing argument, Halpin used this huge mistake to discredit Hernandez, making him appear a fool to the jury. After the trial some of the jurors called Daniel and Arturo “idiots”.

Habeas Corpus, page 476. Prosecutor Halpin made no pretence of hiding his disdain for Daniel and Arturo Hernadez, their in-court bickering appearing in news articles more than once.

L.A Times, November 4th, 1986.

Are You Beginning to See a Pattern?

If one was being kind, one could believe that the pressure of the case, the lack of funding and Daniel’s health could invoke a feeling of sympathy for the beleaguered defence team. However, I am not inclined to feel anything other than disbelief when viewing the entirety of their misdemeanours, failures and lack of consideration for their client.

Their monetary concern overrode all, and one can only wonder if their agreeing to defend Ramirez was based on the thoughts of a fat, lucrative book or movie deal landing in their laps, which, possibly, Manny Barraza, another lawyer involved with the Ramirez family, assured them would happen. Barraza himself did very well in his association with the trial. (He was later imprisoned on corruption charges unconnected to the Ramirez case).

Sympathy is drowned out in a rush after the realisation that this pattern of behaviour was nothing new. It was their modus operandi.

The People V Headley

In 1985, the appeal court in San Francisco found attorney Daniel Hernandez “professionally deficient” in his representation of another man who was convicted of murder. The appeal panel, who declared Daniel ineffectual as a lawyer, reprimanded him for inadequate research and case preparation. However, they declared that it didn’t do enough damage to the defence to warrant a new trial.

The San Jose defendant, Mark Anthony Headley, was sentenced to 26 years and, after conviction, sought new lawyers stating he had been denied effective assistance of counsel during his trial.

Santa Clara Superior Court Judge, Lawrence Terry, found Hernandez ill-prepared for counsel. In circumstances similar to the Night Stalker trial, he failed to subpoena witnesses and inspect the evidence, nor did he properly research the law.

L.A Times, 26th January 1986 Judge Soper, who at the time the Hernadezes took on Richard’s case, was fully aware of the proceedings in Clara County but still allowed the change of attorneys to go ahead as long as they informed Richard of any complaints against them. They could tell Richard whatever they wanted; he was struggling with his own mental problems and didn’t appear to understand what was in his best interests; his family had found these lawyers for him.

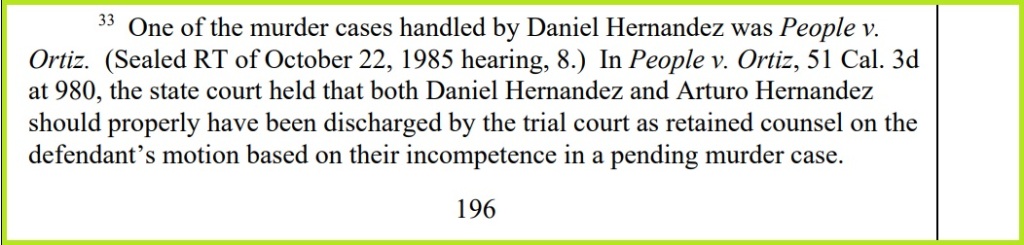

“Moreover, the court was aware that both Daniel Hernandez and Arturo Hernandez had been held in contempt of court in Santa Clara County, and a contempt matter involving Daniel Hernandez was currently pending in Santa Clara County. (XVII CT 4986.) The trial court ordered Daniel Hernandez and Arturo Hernandez to disclose to Petitioner all instances of complaints by former clients, any State Bar investigation, citations for contempt of court, and prior allegations of ineffective representation.19 The court took the matter of substitution of retained counsel under submission. (Id. at 4988-89.) The court continued Petitioner’s arraignment to October 24th, 1985”.

(Id. at 4980-90; XIX CT 5469.) Habeas Corpus, page 33.Allen Adashek, the public defender who so briefly represented Ramirez, arranged for an independent attorney, Victor Chavez, to advise him on the best course of action in choosing his defence; Richard refused to meet with him and fired Adashek due to pressure from his family, and his own paranoia. In Richard’s mind, the public defenders, attached to and appointed by the court, must be working for “the other side”. Manny Barraza was busy fuelling this paranoia by telling the newspapers that Adashek was searching for a book deal, which is clearly not true. Adashek was fully funded by the State.

The intense paranoia experienced by Ramirez concerning court officials reared its head again when he insisted that juror Fernando Sandejas be dismissed from the jury after he discovered that Sandejas and Adashek had attended the same school. The fact that Adashek was a public defender and was working for his best interests was wholly lost on Ramirez.

The People V Ortiz

“Daniel Hernandez disclosed to the court that he was counsel of record in the trial court in People v. Ortiz. In People v. Ortiz, 51 Cal.3d 975, 800 P.2d 547, 275 Cal.Rptr. 191 (1990), which involved the same attorneys, the California Supreme Court held that the trial court should have discharged Daniel Hernandez and Arturo Hernandez on the defendant’s motion based on their incompetence in that pending murder case. Their acts of ineffectiveness in Ortiz occurred at the same time they represented Petitioner”.

Habeas corpus, page 33.Is it Groundhog Day?

Carlos Shawn Ortiz has the bad luck to be represented by Daniel and Arturo in his murder trial; he, too, had substituted an assigned public defender in favour of them.

His appeal, People v. Ortiz, 51 Cal.3d 975, 275 Cal. Rptr. 191, 800 P.2d 547 (Cal. 1990) cites the same misdemeanours experienced by Headley and Ramirez.

On 10th October 1985, Daniel Hernandez was held in contempt for failing to appear in court. That’s unsurprising as he had just been substituted onto the Night Stalker case and was in L.A. He was fined $100 and eventually paid $2500 for being found in contempt of court. Could these numerous fines have contributed to their financial woes?

In January 1986, Carlos Ortiz filed a Marsden motion to get Daniel and Arturo Hernandez dismissed from his case for failing to defend him adequately. He stated they did not appear in court, return his calls, or explore potentially exculpatory evidence concerning blood samples.

Daniel and Arturo blamed the defendant, saying he had lost confidence in them. Who can blame him? Similarly, they blamed the family for not paying them, which leaves the question of whether an indigent client “gets what he pays for” – or not.Ortiz felt that their time was taken up with the Night Stalker trial, running concurrently with his, and that was where their focus was. I doubt Ramirez would agree, for although Daniel and Arturo did blame the L.A trial for their constant delays and waiving of time, they simultaneously were not appearing for Ramirez.

The Ortiz case went to two trials, the first being declared a mistrial due to juror misconduct. The Hernandezes represented him at both, and he was eventually convicted. His appeal was denied because the appellate court opined that he had not demonstrated effective denial of counsel.

If one is poor, the judicial system is a lottery, one with zero chance of winning.

Habeas Corpus, page 196.

San Francisco

Another busy day of incompetence. Oh no, they didn’t, did they? In what seems almost a pantomime, and yet is another repetition of the Los Angeles farce of October 1985, Daniel and Arturo arrived at the San Francisco court intending to represent Ramirez in the pending Pan trial.

San Francisco Examiner, 5th December 1989. On this occasion, Richard stuck with his new attorneys, Michael Burt, Daro Inouye, Dorothy Bischoff and, (until he dismissed him), Randall Martin. Eventually, the Pan trial was stayed indefinitely due to his inability to assist his defence rationally.

You can read about the San Francisco case HERE.

Afterwards

Daniel Hernandez died in 2003.

Arturo is still a practising lawyer. Here is a review of his performance from last year, some things never change.

Review from his website.

The articles concerning the attorneys are some of the least read that we write, but they are crucially important to understanding the trial of Richard Ramirez.

I will leave the last word to one of the jury members, in this instance, the dismissed Fernando Sandejas:

“The the prosecutor was well prepared and presented an orderly case, the attorneys Richard Ramirez hired to defend him were both idiots. I questioned why Ramirez picked them to represent him. They had never tried a capital case before. The lead defense attorney looked lost. His demeanour and poor presentation made it obvious that he had no idea what he was doing”

Document 20-8.

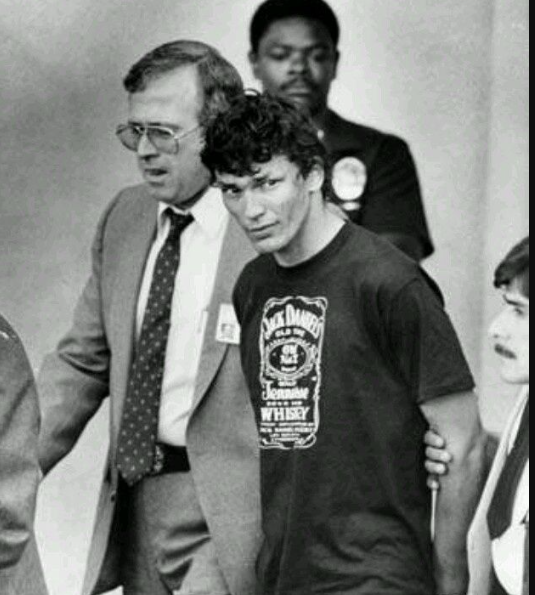

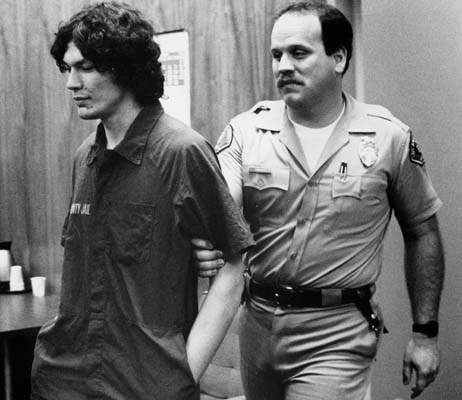

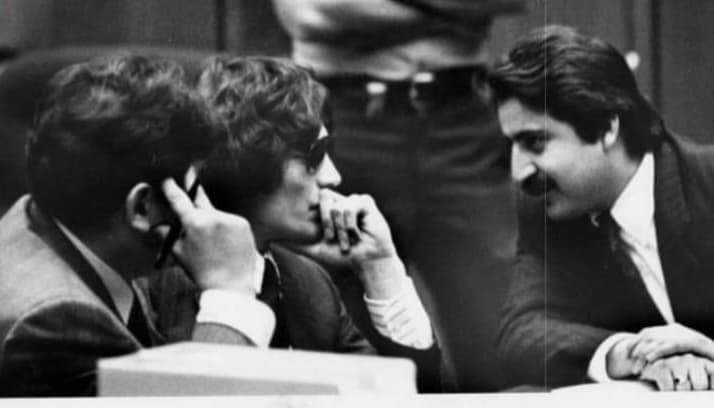

Ramirez with Richard Salinas, dated 20th September 1989, Photo credit: Michael Haering from the Herald Examiner Collection. Additional sources: Sixth Amendment Center – Home (6ac.org) and People v. Ortiz, 51 Cal.3d 975 | Casetext Search + Citator

~ Jay ~

-

Something was Terribly Wrong with Miguel

Many of us probably think we know who Miguel Valles was. After all, we have heard stories about “crazy cousin Mike.” As with most things, there’s more to the story than we know. So, who was Miguel? And why has he gotten so much press when it comes to Richard?

Miguel Angel Valles was born June 14, 1949, in Durango, Mexico. His parents were Juan Valles and Sebastiana Barscnas. He was the nephew of Julian Ramirez Sr., making him Richard’s first cousin. Miguel moved to El Paso with his family at the age of 13. He was married three times and depending on which report you look at he had between 4-7 children, including one that passed away at the age of 5, Miguel Jr, in a gas explosion accident in 1973.

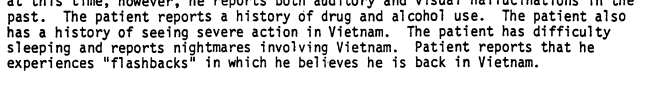

Miguel joined the United States Army in 1970 during the Vietnam war. Although precisely what Miguel did during his time in service is subject to speculation, we do know he was involved in direct combat. Per his own report, he saw a lot of “action” while in Vietnam.

So, what did Miguel do in Vietnam that caused him to have nightmares and flashbacks after he was discharged from the Army?

The Phoenix Program

The Phoenix program was developed in 1967 by the Central Intelligence Agency and it combined existing counterinsurgency programs in a collaborative effort to “neutralize” the Vietcong infrastructure. The word “infrastructure” refers to those civilians suspected of supporting the North Vietnamese and the Vietcong. Phoenix targeted civilians, not soldiers. South Vietnamese civilians whose names appeared on blacklists could be kidnapped, tortured, murdered, or raped simply on the word of an anonymous informer. Phoenix “neutralizations” were often conducted while victims were home, sleeping in bed. Vietcong sympathizers were brutally murdered and tortured along with their families to terrorize the neighboring population into a state of submission. Such horrendous acts were often made to look as if they had been committed by the enemy. Based on Miguels own statements that he saw “severe action” in Vietnam and had flashbacks and nightmares related to his experiences, he may have been a part of the Phoenix program. (This is by no means a comprehensive account of what the Phoenix program was or of what occurred during the Vietnam War).

Miguel was honorably discharged from the Army in December 1971. Three months after he was discharged from the Army he was hospitalized and diagnosed with schizophrenia. This would be the first of numerous hospitalizations for Miguel related to schizophrenia and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Miguel was discharged from the Army with a 100% disability rating. The U.S. government does not hand out 100% disability ratings lightly, so whatever Miguel experienced in the war was deemed by the U.S. government to warrant a rating of being totally disabled.

It’s reported in various places online and in Philip Carlo’s book “The Life and Crimes of Richard Ramirez” that young Richard hung out with his cousin Miguel quite a bit and was enthralled with the stories Miguel told about his time in Vietnam. While Richard did spend time with Miguel based on his own statements, he could not have spent as much time with him as some would have us believe. To see just how much time Richard may have spent with Miguel and how much of an influence he could have had over young Richard’s life, we need to break down the timeline of events in Richard and Miguel’s lives.

- Miguel enlisted in the army in 1970. Richard was 10 years old at the time, and Miguel was 21.

- Miguel returned from Vietnam in late 1971 and was hospitalized in early 1972. By all reliable reports, Richard was still involved in school and hanging out with his friends.

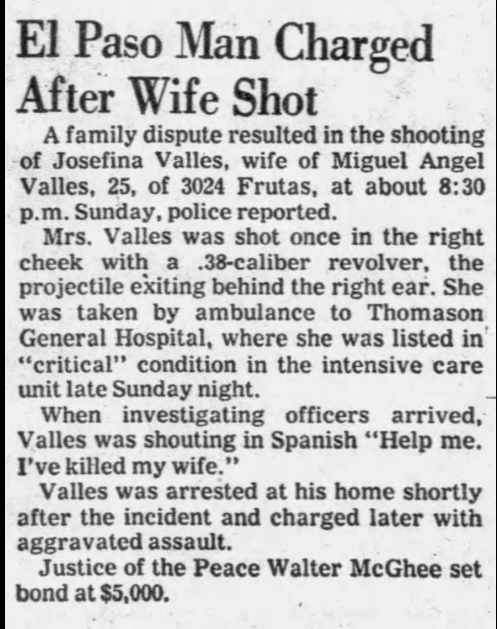

- On May 4, 1975, Richard was at Miguel’s home when Miguel shot his wife, Josefina, leaving her seriously wounded. Miguel was arrested and sent to jail. She passed away 11 days later. Miguel was declared unfit to stand trial for the murder of his wife. As a result, he was sent to Rusk State Hospital for 2 years. Miguel served a combined total of 5 years in jail/prison and a mental hospital for killing his wife.

- Richard spent the majority of 1977 in reform school at Texas Youth Council.

- Miguel spent 1975-1980 either in a mental health facility or jail/prison. So, it’s safe to assume that he had no contact with Richard during this time.

- 1979-Richard moved to California, a year before Miguel was released from prison.

Courtesy of the El Paso Times

Perhaps Richard did see Miguel as a war hero after he returned from Vietnam, regaling Richard and anyone that would listen about his adventures during the war. Per family statements we know it wasn’t just Richard that Miguel told about the rapes and murders he committed during the war. He also spoke of his exploits to other family members. Family members gave statements in 2008 that described Miguel’s behavior after returning from Vietnam.

“Miguel constantly talked about the horrible things he had seen and done in the war. On more than one occasion, I had heard Miguel say that he kept the gun in the fridge because he liked the feel of cold steel when he killed someone.

After Miguel killed his wife, I asked Richard about the incident, and he replied that he didn’t want to talk about it. Richard was starting to become more of a loner and he often kept things to himself.”

– declaration of Ignacio Ramirez, exhibit 102, habeas corpus document 20.5

After Richard witnessed the murder of Miguel’s wife, he appeared to have suffered from severe emotional trauma. He was frightened of Miguel and afraid Miguel would harm him if he told anyone about what happened the day Josefina was shot. He also told hid friend Eddie. In error, Eddie refers to Miguel as an uncle.

“Ricky told me he had an uncle [sic] who was crazy and he was afraid of him. He told me that I couldn’t tell anyone what he was going to say to me and then he said that his uncle killed his … wife right in front of Ricky. Ricky was at his uncles house and an argument flared up. Then the uncle killed his wife. The uncle told him he would kill him if he told anyone and Ricky was terrified. I never saw Ricky look so scared”

– declaration of Edward Milam, habeas corpus document 20.8.

Hospitalizations & Incarcerations

Miguel had an extensive history of being hospitalized for schizophrenia. He also spent time in jail and prison after he killed his wife.

- 1972-first hospitalization

- 1975-incarcerated in El Paso jail

- 1976-1978 Rusk State Hospital

- 1979-1980 Texas Department of Corrections (prison)

- 1982-Miguel was hospitalized four different times (January-February, April, July-September, December -January 1983)

- 1983-hospitalized in March & September

- 1984-hospitalized four times (March-April, May-June, August -September, & November-December)

- 1985-hospitalized October-December

- 1986-hospitalized June & August

- 1988-August & September

- 1989-July-September

- 1990-August

- 1992-September

- 1994-January

*Statement from Mercedes Ramirez in 2008 federal writ of habeas corpus petition.

When we look at all that was going on in Miguel and Richard’s lives from 1970-1979, it’s pretty clear Miguel had a lot more going on than hanging out with his teenage cousin. He was married twice during that time period and had several children. Miguel was repeatedly in and out of the hospital due to his mental health, often involving lengthy hospital stays. He also spent time in jail and prison. Richard was still attending school regularly, at least until around the age of 15, when Miguel killed his second wife. After Miguel killed his wife, he obviously wasn’t spending anytime with Richard and when he was released, Richard had moved to California.

“There’s no thrill like a good kill. ” A statement attributed to Richard, but it was actually Cousin Miguel that Richard was quoting, likely referencing his exploits in Vietnam.

Richard stated in his 1992 interview with Philip Carlo that his dad taught him how to use a gun. Not Miguel. Richard also said in other interviews that he went hunting with his dad as a kid. Let me be clear: the kind of guns used to hunt is nothing like any of the weapons used in the so-called Nightstalker crimes. Many people assume Richard learned how to wield a knife from Miguel. Richard also stated in the interview with Carlo that Miguel told him how he cut some of his victim’s throats in Vietnam with a “stab-slash” cut. However, being told how someone killed their victim does not make you proficient at that method. So to say that Miguel taught Richard how to be a killer is a huge leap of the imagination that has been made by numerous individuals. After breaking down the evidence and the timeline of both Richard and Miguel’s lives, this hardly seems likely.

Miguel not only had serious mental health issues, but he also had physical ones, such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and substance abuse. All of these complications led to a shortened life for Miguel, and he passed away at the age of 45 from a heart attack.

Sources: 2008 Federal Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus, Richard Ramirez v. Robert Ayers & supporting documents submitted with 2008 federal writ-Document 20-7 and 20-8, Miguel Valles medical records (available upon request).

We now have a book out! Currently on all Amazon marketplaces! Click the image below.

You must be logged in to post a comment.