“San Quentin, what good do you think you do?

Do you think I’ll be different when you’re through?

You bent my heart and mind, and you warp my soul.

Your stone walls turn my blood a little cold.”– Johnny Cash “San Quentin“

Founded in 1852, San Quentin State Prison is California’s oldest correctional facility. Located on a peninsula north of San Francisco in Marin County, San Quentin is surrounded by barbed wire fence, tall walls, and watch towers with expert sharpshooters and assault rifles. Yet, it boasts breathtaking views of the San Francisco Bay. San Quentin was initially established to replace a prison ship. Legend has it that on July 14, 1852, Bastille Day in the French Revolution, the ship arrived off the coast of San Francisco with over 40 prisoners. Hence, San Quentin has been known as the “Bastille by the Bay.”

San Quentin has been the site of executions in California since 1893. In 1938, lethal gas became the official method of capital punishment, with prisoners being gassed to death in the sinister, 7½-foot-wide, octagonal, green death chamber. In 1972, the United States Supreme Court struck down the death penalty, declaring that “the imposition and carrying out of the death penalty constitutes cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments,” only to reinstate it in 1976.

Since then, over 1,000 people have been condemned to death in the state of California, including Richard Ramirez. Of that 1000, 13 have been executed, while more than 100 have passed away from other means inside the prison walls.

Due to the lengthy appeals process in the state and the procedural safeguards required by the courts in capital cases, prisoners typically spend over 20 years on death row. They are more likely to die from illnesses, suicide, or be killed by a fellow inmate or prison guard than executed. The vast majority of those sentenced to death have been people of color, and more than one-third of individuals on death row have been diagnosed with severe mental illness.

The Adjustment Center

The Adjustment Center is SQ prison’s maximum-security cell block, also known as “the hole.” This is where prisoners are sent for punishment, and new death row inmates begin their sentences. It is described as a “prison within a prison.”

The Adjustment Center is the harshest of the three death row units at San Quentin. It is severe even compared with other isolation units in the California prison system and most death row units in other states. Residents spend between 21 and 24 hours a day, sometimes for years, inside cells smaller than a standard parking space. There is no natural light (cells do not have windows) or airflow; temperatures fluctuate from hot to cold. Beds consist of a thin mattress on steel or concrete slabs; there are no chairs or desks.

Those living in the Adjustment Center are constantly exposed to noise due to the slamming of security gates and cell doors and residents shouting or banging, either in attempts to communicate with one another or as a primal response to their intolerable conditions. The ongoing commotion contributes to chronic sleep deprivation, one of the many adverse health effects of long-term confinement in the Adjustment Center.

Before and after any movement within the Adjustment Center, inmates are routinely strip-searched, often in front of other prisoners and guards, even if they have not come into contact with anyone else during their time out of the cell.

Inmates may only leave their cells for a few reasons:

- Yard visits, in an exercise “cage,” at most three times per week for three hours each.

- Showers (no more than three times per week).

- Medical visits (ONLY if prison guards decide you warrant a trip to medical).

- Rare opportunities for visitors, which occur behind a dirty Plexiglas window through a poor-quality two-way intercom.

Richard Ramirez in “The Hole”

On November 17, 1989, Richard found himself being flown by helicopter from the Los Angeles County Jail to the San Quentin Adjustment Center. The cell was 6’x8′ cell with an aluminum toilet, sink, and bunk bed. Per Philip Carlo’s The Life and Crimes of Richard Ramirez, Richard’s cell was “3AC8” pictured below.

He had no phone access and was only allowed visitation through a Plexiglas window for two hours a week. He remained here until he was transferred to the San Francisco County Jail to await trial for the Pan crimes in February of 1990. He was transferred back to San Quentin on September 21, 1993, although legal proceedings had not concluded in S.F. This is because his “groupies” presented security problems. The following is from the San Francisco Examiner:

“The [San Francisco County] Sheriff’s Department sought the transfer because “the Sheriff’s staff must spend an inordinate amount of resources in an effort to accommodate Ramirez. [He] has numerous visitors … which require an additional deputy to be assigned to the jail’s visiting lobby.”

– San Francisco Examiner, September 3, 1993

Richard was returned to the Adjustment Center. Even though a prisoner was not supposed to be kept there for longer than three months, Richard spent over three years there. His attorney, Michael Burt, had to make repeated requests to prison officials for Richard to be moved to a unit where he could have phone access and increased visitation.

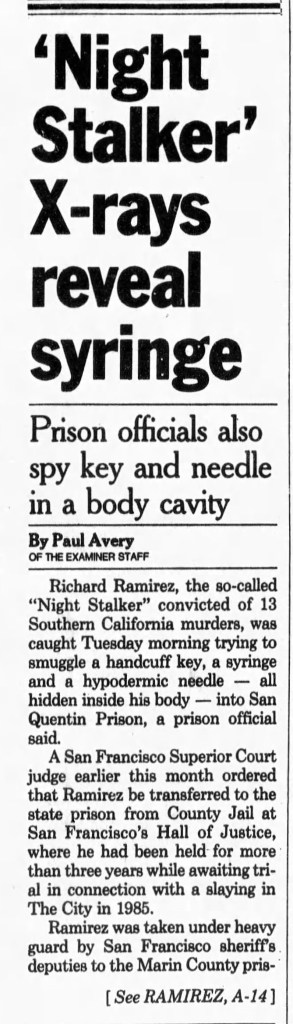

When Richard was transferred, prison guards performed a metal detector scan that revealed Richard allegedly concealed objects inside his body. Consequently, he was escorted to the prison hospital, where an X-ray confirmed the presence of items in his rectum. We can only speculate on the desperation that compelled Richard to resort to such extreme measures – that is if the story is true. Below are two newspaper clippings.

East Block

Richard was moved to East Block, the five-tier, main death row cell at San Quentin, in June 1996. This is where he spent the remaining 17 years of his life. There are few sources available detailing what life was like for Richard as a condemned prisoner. In his interview with Philip Carlo, Richard said his cell in East block was even smaller than the one he had occupied at the Adjustment Center.

Although Carlo used creative license in writing his book, he did include excerpts from his interviews with Richard in the special update of the tenth-anniversary edition. Below is a portion of an interview conducted by Carlo while Ramirez was incarcerated in East Block:

“Carlo: What’s it like living on death row, Richard?”

Ramirez: It is monotonous, it is boring … because it is so boring it breeds tension. There’s a lot of tension in here. Frustration … you never get used to it. I myself only tolerate it. I have acquaintances – no friends. Every day, it’s the same routine. The walls close in on you.

Carlo: How many hours a day are you actually in your cell?

Ramirez: Well, like I told you, the program they have me on now – which is maximum security – I got out sixteen hours a week.

Carlo: So are you locked up twenty-four hours a day?

Ramirez: On some days, some days, yeah. I go outside for about five hours on Tuesday, I got out five hours on Friday and I go out five hours on Sunday.

Carlo: How’s the food on death row?

Ramirez: Edible.

Carlo: Are you able to eat with the prisoners on death row or do you –

Ramirez: They feed us in our cages.

Ramirez, in his interview with Carlo, gave his opinion on how unnatural it felt to be on death row.

“Sometimes it feels very strange to wake up and be in that cage, in that cell and … I don’t think man was meant to be locked up in such a way. Maybe they had a thing going on in the Western days [old West] where they would just lynch the guy right off the bat, see what I’m saying? But they don’t do it now like that.”

Richard theorized on the reasons the death penalty appeals to people and who is more likely to end up on it:

“Ramirez: As far as the death penalty is concerned, I think it is a power against the powerless. There are not many millionaires on death row … The death penalty is … to me … is not a very dignified way.

Carlo: Do you think that the government does not have the right to take a life, or do you feel that in certain crimes –

Ramirez: Well, they’re doing it for the victims. If the relatives of the victims want the killer’s blood … uh … I think one of the relatives should pull the plug, the switch. But they leave it up to the state and … that is something to look at.”

Death Row Romeo

In a Current Affairs episode aired in 1991, Richard was labeled the “Death Row Romeo” due to his reputation with “groupies.” How does one become a “Romeo” when locked behind iron bars, under the watchful eye of security guards 24 hours a day?

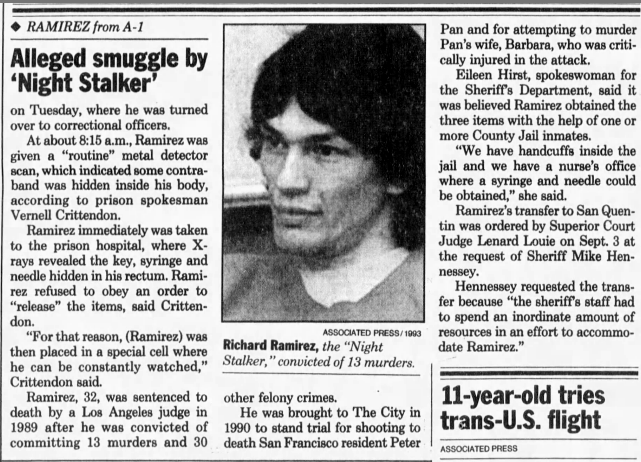

Ramirez downplayed his “sex symbol” status as shown in this San Francisco Examiner article, dated August 3, 1991. It claims that eight to 10 women arrive every week. Other times, there were so many that they had to be turned away.

Richard was modest about why women were visiting him. It says:

“He said reports on the number of his female visitors were exaggerated. “The ones who do visit me are sympathetic.”“

While many women wrote letters to Richard and visited him, that was the extent of his relationship with most of them, as he was not allowed physical contact visits, except for Night Stalker trial juror, “Cupcake” Cindy Haden, and Doreen Lioy – who later married Richard.

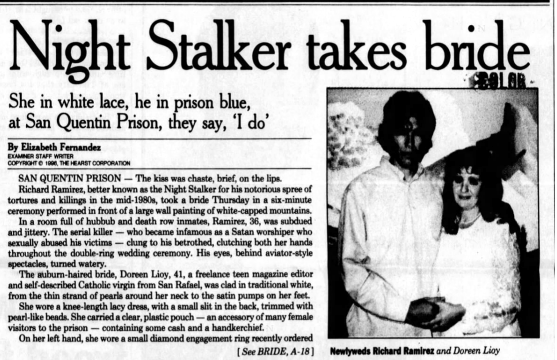

Haden was only allowed physical contact visits after becoming a private investigator and alleged that she wanted to help with Richard’s case. Doreen wasn’t allowed contact visits until Richard was moved to East Block in 1996, four months before the “Death Row” wedding, on October 3, 1996. Below are two newspaper clippings about his marriage.

Carlo’s interview concludes with Richard’s hopes for his future:

“He says he was railroaded and has hopes in the appeal. He has changed much in the eleven years since August of 1985. He’s gained thirty-five pounds and he’s mellowed out … But by no means has he adjusted to the reality of his existence. He does not like being in the adjustment centre, saying it’s cruel and unusual punishment, and he often paces his cell like a caged panther … Richard believes he will win the appeal, win at a new trial, and be set free”

Additional Sources

2008 Federal Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus, Richard Ramirez vs. Robert Ayers

Night Stalker. The Life and Crimes of Richard Ramirez, Philip Carlo, 1996

https://www.cdcr.ca.gov/facility-locator/sq/

A look at the hard life inside San Quentin’s Death Row (sfgate.com)

What it’s like on California’s Death Row | KCRW

KayCee

Jan 14, 2024

Leave a comment