*images may need desktop viewing for clarity*

“After a recess, in another hearing held in the court’s chambers which was held outside of the presence of Petitioner, the court and the parties discussed courtroom security. Trial counsel was concerned that there had been no screening of the members of the public which were coming to watch the trial. Trial counsel was concerned because the defense attorneys had received death threats”.

Petition of Habeas Corpus, page 578

The above quote is taken from the main document of the 2008 petition; it is regarding a hearing concerning security within the courtroom; death threats had been made towards the defence attorneys by members of the public who felt that Ramirez should not receive legal representation. These same people were probably of the same opinion as Mayor Tom Bradley, who declared to the press that a trial wasn’t needed as he was guilty, and he knew that based on the evidence he had seen.

This statement, made after his award ceremony honouring the “Hubbard Street Heroes”, is one of many made to the media before the arraignment. One can imagine the mayor, followed by an array of torch and pitchfork-waving citizens, hustling Ramirez up to the door of the gas chamber; no trial needed. What a strange understanding of “liberty and justice for all”. Death threats for simply trying to do their job?

Mayor Bradley and the people of Los Angeles, collectively suffering from memory loss, forgot that under the 6th Amendment, every defendant is entitled to a fair trial and the effective assistance of counsel.

This is part four in a series of posts about the defence.

Lawyer Roulette – Cronic and Strickland, a Brief overview

The petition repeats two words: “Cronic” and “Strickland”.

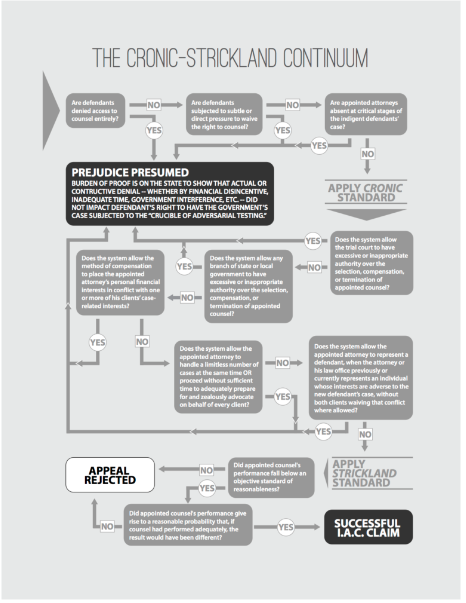

So what do they mean? In brief, Cronic and Strickland are two Supreme Court cases that decide the two-pronged testing used to determine the effectiveness of counsel, principally for indigent defendants.

Strickland looks back at a trial where the outcome has already been determined and asks if the attorneys provided effective assistance of counsel and if incompetence prejudiced the outcome.

Cronic looks forward at the start of the proceedings to try and assess if certain factors are present or absent, and if so, the court should assume that ineffective assistance of counsel will occur. (Source: 6ac.org)

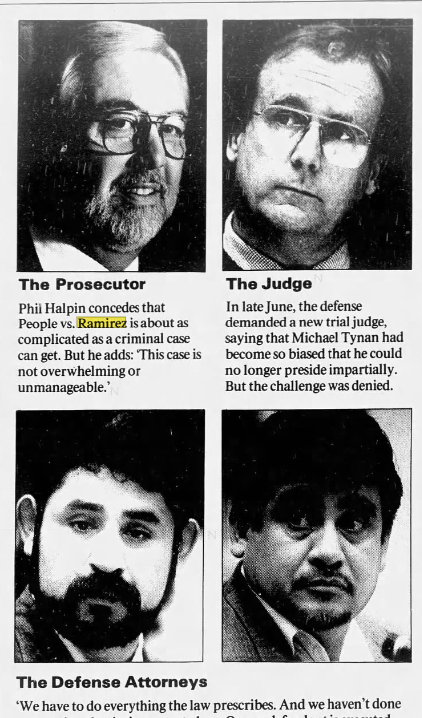

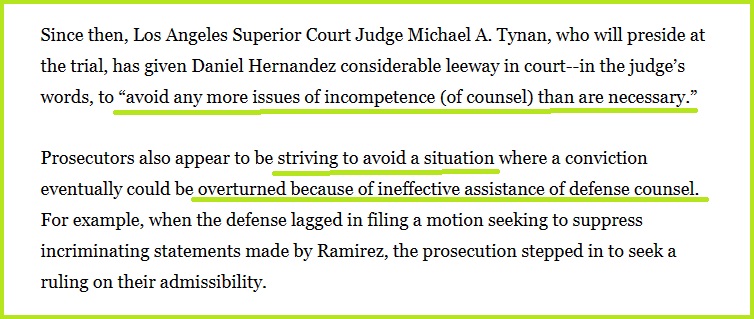

Prosecutor Halpin, well aware of the implications, had to remind Richard’s attorneys how to do their job more than once.

“The overarching principle in Cronic is that the process must be a “fair fight.” Cronic notes that the “fair fight” standard does not necessitate one-for-one parity between the prosecution and the defence. Rather, the adversarial process requires states to ensure that both functions have the necessary resources at a level their respective roles demand.“

As the U.S. Supreme Court notes: “While a criminal trial is not a game in which the participants are expected to enter the ring with a near match in skills, neither is it a sacrifice of unarmed prisoners to gladiators.”

“Cronic’s necessity of a fair fight requires that the defence attorney put the prosecution’s case to the “crucible of meaningful adversarial testing.” A constructive denial of counsel occurs if a defence attorney is incapable of challenging the state’s case or barred from doing so because of a structural impediment.”

Source: 6ac.org

The Judicial Lottery

On January 6th, 1987, the court gave the following soliloquy in a closed session. This was exactly two years before the L.A. Times news report above.

“Now, I am calling this hearing, Mr. Ramirez, to tell you that I reluctantly have to tell you that in my opinion your lawyers are incompetent.

Now, I have had this case for six months, and I must say that I am convinced that your lawyers are nice guys, good company, maybe good fellows to spend an evening with. I am also convinced that they are dedicated to your defense emotionally. But I must tell you that, in my opinion, they are not competent to handle your case.

I don’t think that they have sufficient experience in the law. I don’t think that they have the staffing, if you will, or whatever, to do the job…I am telling you now…I don’t think they know the law well enough, I don’t think they know the rules of evidence well enough, they are not ready to present the evidence and push it through….I am just telling you this because I have no personal axe to grind at all, I simply want to see that whatever happens in this case is done right and you get your rights protected, that whatever conclusion is reached is right. And I am telling you now that your rights are not being protected.”

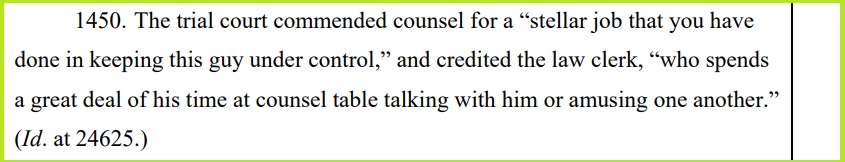

Habeas Corpus, page 204 – Judge Dion Morrow – Prosecutor Halpin moved to have him taken off the case.

When the Hernandezes initially requested to substitute themselves in place of Joseph Gallegos, Arturo assured the court that they were fully funded and that paying for the defence wouldn’t be a problem. “All the resources are there…no matter how long it takes” (from a hearing on October 22nd, 1985). He failed to inform that court that there had been no money incoming from the family and that they hoped to be paid from the proceeds of any film or book deal obtained. When the hoped-for agreement didn’t materialise, as Ramirez refused to sign a contract, Arturo took on extra cases, alongside Richard’s trial, for the next four years.

Even before the trial began, the lack of funding available to the defence was causing delays; Arturo explained to the court that as “Mr Ramirez is an indigent defendant he doesn’t have the means or resources , as the People do, to maintain as pace that is required by the People”. (from a recorded transcript 906-907)

The court, inpatient and annoyed, chastised the Hernandezes for their constant tardiness and for raising financial concerns for their delays. They had, after all, assured the court that their defence was fully funded during the hearing for the substitution of counsel.

“Financial concerns are not reason really (sic) to continue this case. You owe [Mr. Ramirez] a duty of at least warm zeal on this case, and of course, as officers of the court—this court, owe prompt attention to this case.”

(Id. at 3007.) Habeas Corpus, page 230

Daniel Hernandez’s Health

By May of 1987, the Hernandezes closed their local offices, telling the court in a sealed recorded transcript that they were “broke”, and moved back to their office in San Jose. The court appointed another attorney, Michael Carney, to help file motions. The situation didn’t improve; Daniel and Arturo were in San Jose working on other cases and needed to communicate with Carney, which they didn’t. These other cases, worked concurrently with the Night Stalker trial, meant that none of their clients were getting the defence they were entitled to.

In January 1989, with the trial just beginning, Daniel Hernandez tried to force the court into giving him funding (this would only be allowed if the court agreed to appoint him, which they refused to do), claiming that his client’s defence would suffer without additional funding.

“Mr. Hernandez, when you tell the court that if you don’t get appointed you are going to withdraw, or if you don’t get appointed you are going to do less than diligent work on this case, as you appear to state in these motions, that is frightening to me because that is extortion. And I will be honest with you, this court is not going to be extorted.”

(Judge Tynan. Sealed January 20th, 1989, 140A RT 16005.)

Judge Tynan accused Daniel Hernandez of lying to Judge Soper about their financial situation at the time of the substitution in October 1985. Extortion failing, Daniel tried another tactic in that he was too ill with stress to function correctly as an attorney. One might question his ability as an attorney in the first place, with or without stress.

“Perhaps realizing its deficient performance, counsel admitted, “I am under some medication, I am not making a lot of sense sometimes, and I advise the court I have been under medication for the last two weeks. Let the record be clear that if you are having some problems, it is perhaps because of my medication.” (16 RT 741.) A reasonable justification for abridging Petitioner’s right to counsel does not include being medicated.”

Habeas Corpus, page 314, a pithy response from the Habeas lawyers.

In June 89, Daniel again blamed his lack of funds for not presenting any defence witnesses, witnesses like Eva Castillo (who strangely disappeared) and others who should have been investigated. He asked for a delay, which was (unsurprisingly) denied. This was the exchange:

“You are going to be in the same boat, aren’t you? You are dead broke now. You are not eating.”

“I’ve been going without anything for myself for four years and now I have to eat my pride again and say I’m broke, and even then, you stuff it down my throat.” (Sealed June 26th, 1989 hearing, 199A RT 23267). Habeas Corpus Page 233.

The lack of funding was a direct result of their agreement with the Ramirez family; this “conflict of interest” was the price paid by Richard for their unethical, third-party contract arranged by his family. No money was raised, and Arturo Hernandez claimed that the Ramirez family’s inability to pay would cause them “to give less than adequate representation and render ineffective assistance of counsel to our client, because we have to work and try to survive and maintain some sort of practice.” (Sealed September 29th, 1987, 33C RT 2358

Arturo Hernandez appeared to be threatening the court with an inadequate performance unless they were court-appointed. The reasons why the court refused to appoint them, unlike Ray Clark, whom they did appoint, are explained HERE.

Ramirez was stuck in the middle of this battle of wills, unable and unwilling to concentrate. Tynan thanked Richard Salinas, Daniel’s assistant, for keeping him amused, like a child. I am surprised they didn’t supply crayons and a colouring book to complete the gesture.

Timeline of Incompetence

Lists can be tedious. However, this list is essential, demonstrating how badly the defence handled the case.

- From September 26th 1988 to January 23rd 1989, Daniel Hernandez conducted voir dire without the assistance of co-counsel Arturo Hernandez. Voir dire being the process where potential jurors are vetted for suitability for serving and, more importantly, weeded out for biases.

- On October 3rd, 1988, the trial court sent a letter to Arturo Hernandez regarding his absence from the trial.

- On October 18th, 1988, the court issued a body attachment for Arturo Hernandez and ordered it held until October 24th, 1988. A body attachment is a warrant issued by a judge authorising law enforcement to arrest someone and bring them to court.

- October 25th, 1988, Arturo Hernandez appeared in court to explain his absence from trial and requested to be relieved from Richard’s defence, stating he could not communicate with him.

- February 21st 1989, Daniel Hernandez did not appear at trial due to illness during the prosecution’s case-in-chief. This is especially damning; Arturo was also absent, meaning neither of them were present during this crucial moment.

- February 24th 1989, the trial court ordered Daniel Hernandez to inform the court of his medical condition. He failed to do so.

- Neither counsel appeared in court on February 21st and February 27th, 1989; instead, law clerk Richard Salinas appeared on Richard’s behalf.

- On February 27th, 1989, the court continued trial to March 6th, 1989.

- March 1st, 1989, a hearing was held concerning trial counsel Daniel Hernandez’s health. The court determined that there was no legal cause to delay the trial.

- March 6th, 1989: Ray Clark was appointed as co-counsel. It’s far too late for him to be of much use.

- July 13th 1989, prosecutions closing argument, neither Daniel nor Arturo Hernandez were present. Arturo didn’t turn up, and Daniel didn’t bother to return from lunch, causing the jury to be excused for the rest of the day. “As you can see..Hernandez isn’t with us this afternoon. Frankly, we don’t know where he is”. Frankly, that’s just not good enough.

- July 14th, 1989, the court ordered Daniel Hernandez to be present at all hearings and Arturo Hernandez to present himself in court on July 17th.

- July 17th 1989, Arturo Hernandez failed to attend court for the closing argument of the guilt phase.

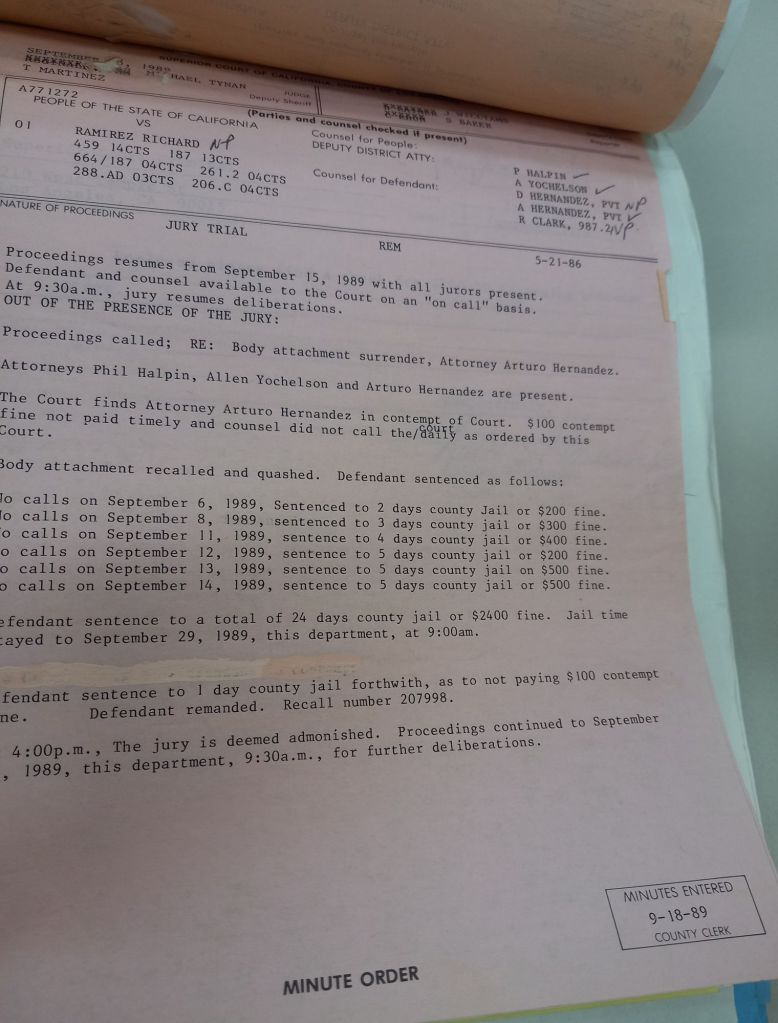

- August 18th 1989, Arturo Hernandez was found in contempt of court and fined. He had told the court he was in Mexico attending his brother’s funeral; he was in Europe on honeymoon. Trial court found him to have abandoned Ramirez.

- September 14th 1989, Arturo Hernandez was again found in contempt for not paying his fine. The court issues another arrest warrant, and bail is set for $5000, but withdraws the accusation of abandonment.

- September 15th 1989, Arturo Hernandez contacts the court.

- September 18th, 1989, Arturo Hernandez paid a cheque for $100. The court sentences him to 24 days in jail or pay a $2400 fine. He’s jailed for one day for late payment of a $100 contempt of court fine.

- September 19th 1989, Arturo Hernandez pays the $2400 fine.

- September 20th 1989, Richard is found guilty.

“Counsel’s lack of qualifications, failures to appear, and incompetence were obvious to the trial judge throughout the proceedings. Furthermore, it is clear that counsel’s deficits endangered the fairness of the proceedings, and diminished the integrity of the legal profession. The trial court erred in allowing Petitioner to stand trial on capital charges with such ineffective representation.”

Habeas Corpus, page 245

In-Court Display Disaster

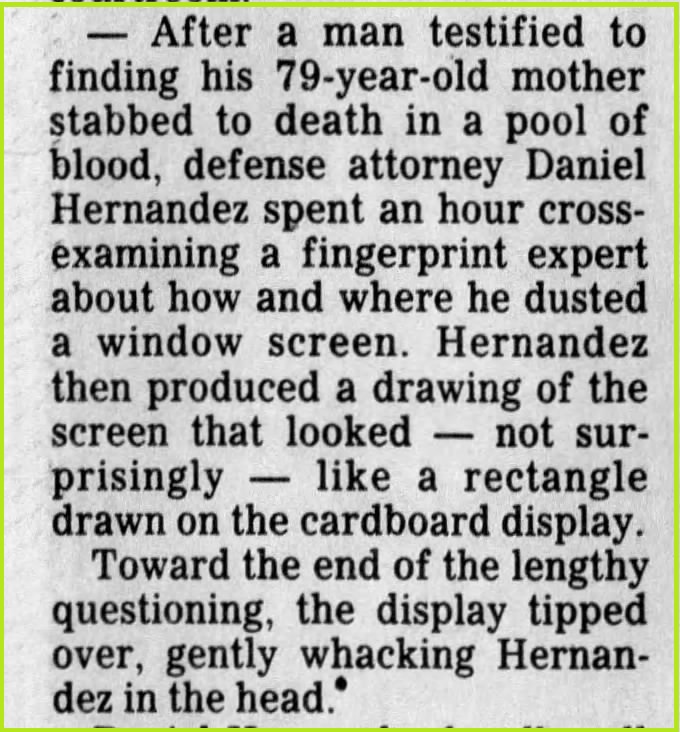

On occasion, Daniel Hernandez made a valiant attempt to defend Ramirez; to say otherwise would be unfair; although lacking technique and the critical skills so desperately needed, his attempts often looked faintly ridiculous.

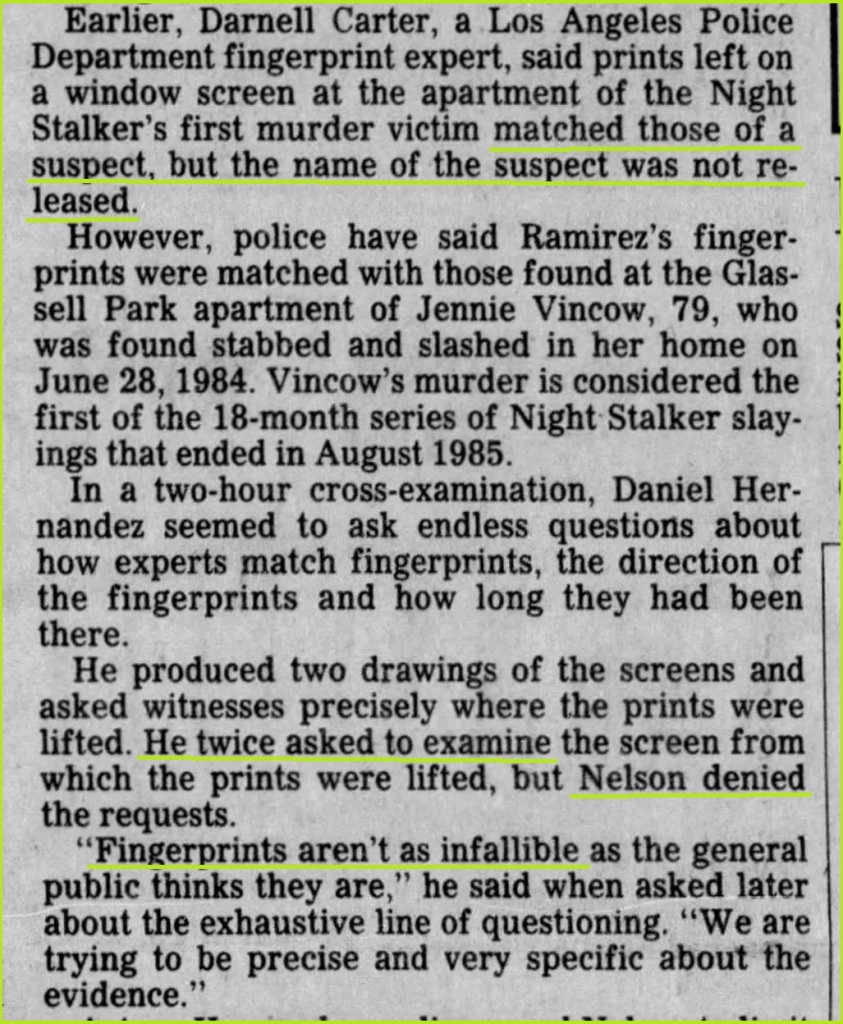

During the cross-examination of the prosecution’s fingerprint expert in the Vincow incident, Daniel spent a couple of hours trying to get the examiner to demonstrate exactly where the alleged fingerprints were on the window screen. He even brought his own in-court display, a piece of cardboard that finally fell on top of him.

The newspaper reporters had this to say:

An LAPD fingerprint expert, Darnel Carter, said that the prints found on the screen at the Glassell Park apartment matched those of a suspect, but the name had not been released. However, the police said the prints belonged to Ramirez, so we hear no more about this.

According to news reports, Hernandez TWICE asked to examine the fingerprint evidence, but Judge Nelson denied his request. Daniel Hernandez was correct when he told reporters that fingerprint evidence is not infallible. Why Nelson refused his request is a question that has never been answered, and refusing the defence a better look at fingerprints seems a common trait; the U.S. Government later refused Ron Smith (fingerprint expert for the defence, post-conviction) a look at them as well.

Those fingerprints were never independently verified. In this instance, we should cut Daniel some slack. Just a little.

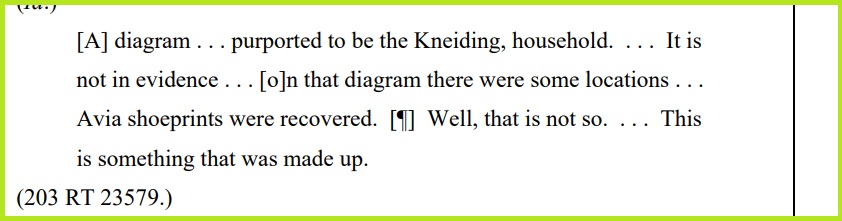

Dodgy Diagrams

As previously discussed in an earlier post, the defence didn’t retain an expert witness to challenge the prosecution’s misleading shoeprint evidence. Daniel rallied to the task with another in-court display, which purportedly showed all the incidents where the Avia shoeprints were discovered. He managed to get it wrong and included the Kneiding incident.

No shoeprints were found at the Kneiding crime scene, which the defence should have known, and getting it so badly wrong is appalling. In his closing argument, Halpin used this huge mistake to discredit Hernandez, making him appear a fool to the jury. After the trial some of the jurors called Daniel and Arturo “idiots”.

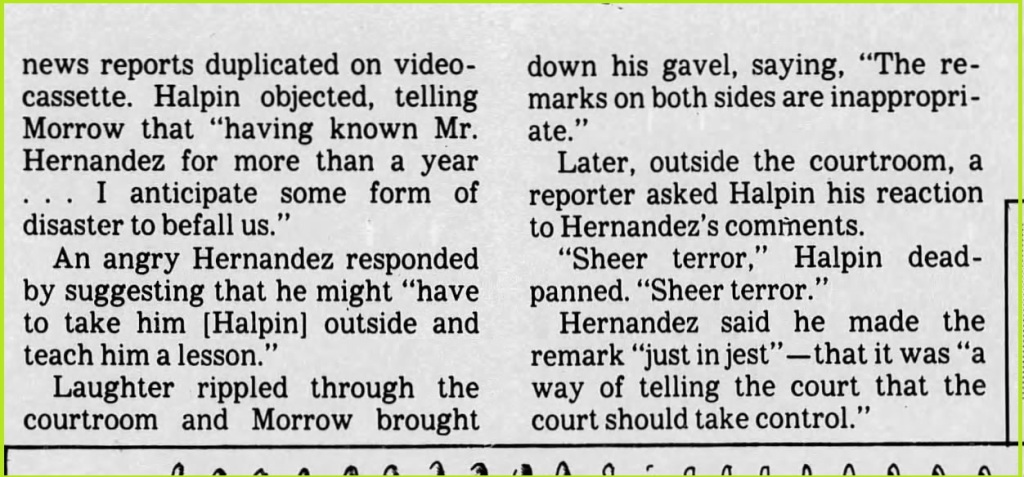

Prosecutor Halpin made no pretence of hiding his disdain for Daniel and Arturo Hernadez, their in-court bickering appearing in news articles more than once.

Are You Beginning to See a Pattern?

If one was being kind, one could believe that the pressure of the case, the lack of funding and Daniel’s health could invoke a feeling of sympathy for the beleaguered defence team. However, I am not inclined to feel anything other than disbelief when viewing the entirety of their misdemeanours, failures and lack of consideration for their client.

Their monetary concern overrode all, and one can only wonder if their agreeing to defend Ramirez was based on the thoughts of a fat, lucrative book or movie deal landing in their laps, which, possibly, Manny Barraza, another lawyer involved with the Ramirez family, assured them would happen. Barraza himself did very well in his association with the trial. (He was later imprisoned on corruption charges unconnected to the Ramirez case).

Sympathy is drowned out in a rush after the realisation that this pattern of behaviour was nothing new. It was their modus operandi.

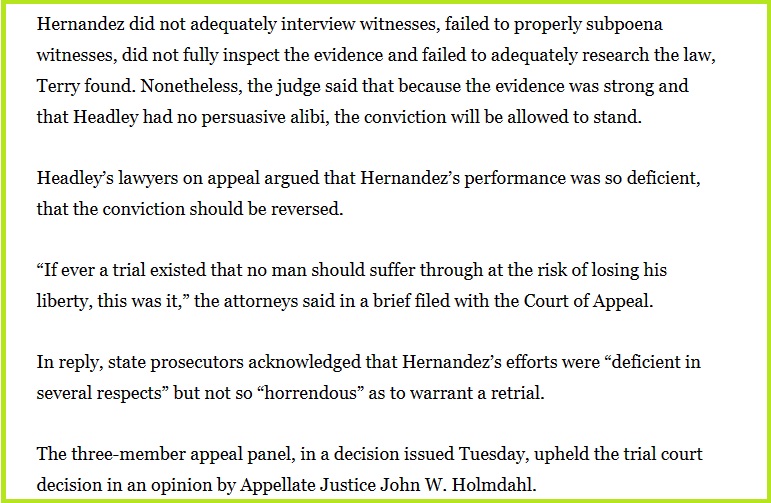

The People V Headley

In 1985, the appeal court in San Francisco found attorney Daniel Hernandez “professionally deficient” in his representation of another man who was convicted of murder. The appeal panel, who declared Daniel ineffectual as a lawyer, reprimanded him for inadequate research and case preparation. However, they declared that it didn’t do enough damage to the defence to warrant a new trial.

The San Jose defendant, Mark Anthony Headley, was sentenced to 26 years and, after conviction, sought new lawyers stating he had been denied effective assistance of counsel during his trial.

Santa Clara Superior Court Judge, Lawrence Terry, found Hernandez ill-prepared for counsel. In circumstances similar to the Night Stalker trial, he failed to subpoena witnesses and inspect the evidence, nor did he properly research the law.

Judge Soper, who at the time the Hernadezes took on Richard’s case, was fully aware of the proceedings in Clara County but still allowed the change of attorneys to go ahead as long as they informed Richard of any complaints against them. They could tell Richard whatever they wanted; he was struggling with his own mental problems and didn’t appear to understand what was in his best interests; his family had found these lawyers for him.

“Moreover, the court was aware that both Daniel Hernandez and Arturo Hernandez had been held in contempt of court in Santa Clara County, and a contempt matter involving Daniel Hernandez was currently pending in Santa Clara County. (XVII CT 4986.) The trial court ordered Daniel Hernandez and Arturo Hernandez to disclose to Petitioner all instances of complaints by former clients, any State Bar investigation, citations for contempt of court, and prior allegations of ineffective representation.19 The court took the matter of substitution of retained counsel under submission. (Id. at 4988-89.) The court continued Petitioner’s arraignment to October 24th, 1985”.

(Id. at 4980-90; XIX CT 5469.) Habeas Corpus, page 33.

Allen Adashek, the public defender who so briefly represented Ramirez, arranged for an independent attorney, Victor Chavez, to advise him on the best course of action in choosing his defence; Richard refused to meet with him and fired Adashek due to pressure from his family, and his own paranoia. In Richard’s mind, the public defenders, attached to and appointed by the court, must be working for “the other side”. Manny Barraza was busy fuelling this paranoia by telling the newspapers that Adashek was searching for a book deal, which is clearly not true. Adashek was fully funded by the State.

The intense paranoia experienced by Ramirez concerning court officials reared its head again when he insisted that juror Fernando Sandejas be dismissed from the jury after he discovered that Sandejas and Adashek had attended the same school. The fact that Adashek was a public defender and was working for his best interests was wholly lost on Ramirez.

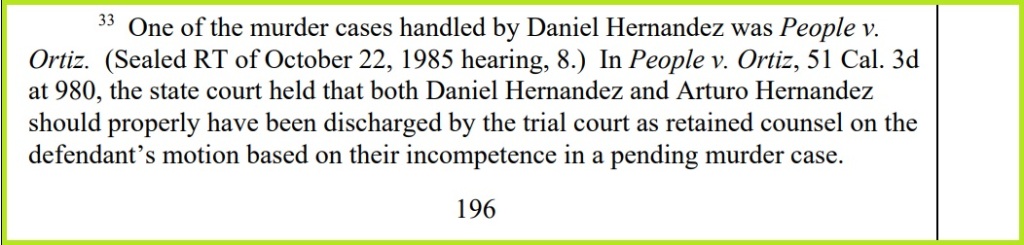

The People V Ortiz

“Daniel Hernandez disclosed to the court that he was counsel of record in the trial court in People v. Ortiz. In People v. Ortiz, 51 Cal.3d 975, 800 P.2d 547, 275 Cal.Rptr. 191 (1990), which involved the same attorneys, the California Supreme Court held that the trial court should have discharged Daniel Hernandez and Arturo Hernandez on the defendant’s motion based on their incompetence in that pending murder case. Their acts of ineffectiveness in Ortiz occurred at the same time they represented Petitioner”.

Habeas corpus, page 33.

Is it Groundhog Day?

Carlos Shawn Ortiz has the bad luck to be represented by Daniel and Arturo in his murder trial; he, too, had substituted an assigned public defender in favour of them.

His appeal, People v. Ortiz, 51 Cal.3d 975, 275 Cal. Rptr. 191, 800 P.2d 547 (Cal. 1990) cites the same misdemeanours experienced by Headley and Ramirez.

On 10th October 1985, Daniel Hernandez was held in contempt for failing to appear in court. That’s unsurprising as he had just been substituted onto the Night Stalker case and was in L.A. He was fined $100 and eventually paid $2500 for being found in contempt of court. Could these numerous fines have contributed to their financial woes?

In January 1986, Carlos Ortiz filed a Marsden motion to get Daniel and Arturo Hernandez dismissed from his case for failing to defend him adequately. He stated they did not appear in court, return his calls, or explore potentially exculpatory evidence concerning blood samples.

Daniel and Arturo blamed the defendant, saying he had lost confidence in them. Who can blame him? Similarly, they blamed the family for not paying them, which leaves the question of whether an indigent client “gets what he pays for” – or not.

Ortiz felt that their time was taken up with the Night Stalker trial, running concurrently with his, and that was where their focus was. I doubt Ramirez would agree, for although Daniel and Arturo did blame the L.A trial for their constant delays and waiving of time, they simultaneously were not appearing for Ramirez.

The Ortiz case went to two trials, the first being declared a mistrial due to juror misconduct. The Hernandezes represented him at both, and he was eventually convicted. His appeal was denied because the appellate court opined that he had not demonstrated effective denial of counsel.

If one is poor, the judicial system is a lottery, one with zero chance of winning.

San Francisco

Oh no, they didn’t, did they? In what seems almost a pantomime, and yet is another repetition of the Los Angeles farce of October 1985, Daniel and Arturo arrived at the San Francisco court intending to represent Ramirez in the pending Pan trial.

On this occasion, Richard stuck with his new attorneys, Michael Burt, Daro Inouye, Dorothy Bischoff and, (until he dismissed him), Randall Martin. Eventually, the Pan trial was stayed indefinitely due to his inability to assist his defence rationally.

You can read about the San Francisco case HERE.

Afterwards

Daniel Hernandez died in 2003.

Arturo is still a practising lawyer. Here is a review of his performance from last year, some things never change.

The articles concerning the attorneys are some of the least read that we write, but they are crucially important to understanding the trial of Richard Ramirez.

I will leave the last word to one of the jury members, in this instance, the dismissed Fernando Sandejas:

“The the prosecutor was well prepared and presented an orderly case, the attorneys Richard Ramirez hired to defend him were both idiots. I questioned why Ramirez picked them to represent him. They had never tried a capital case before. The lead defense attorney looked lost. His demeanour and poor presentation made it obvious that he had no idea what he was doing”

Document 20-8.

Additional sources: Sixth Amendment Center – Home (6ac.org) and People v. Ortiz, 51 Cal.3d 975 | Casetext Search + Citator

~ Jay ~

Leave a comment