By Venning

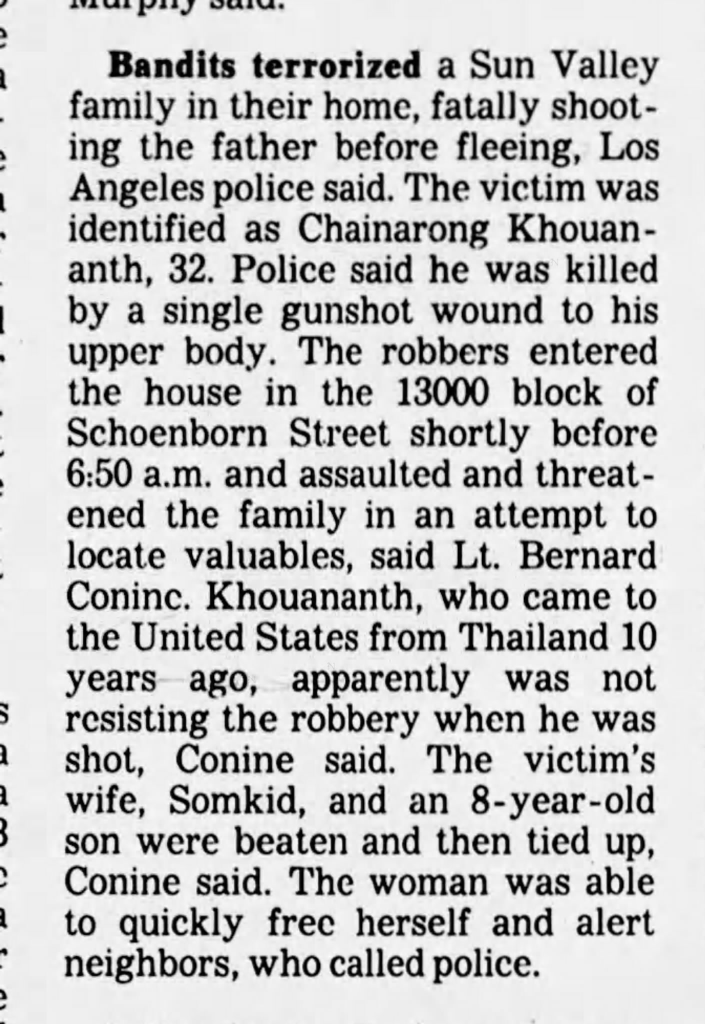

Somkid Khovananth has always been viewed as the most significant Night Stalker eyewitness. She saw him with the light on; it was daylight when the killer departed. She was the survivor who helped police to create the infamous sketch – the one police chose for their BOLO bulletins. The appearance of the suspect in previous murders was later retrofitted by detectives. Those investigators appear on documentaries falsely claiming that all victims described this dishevelled man with stained, gapped teeth.

A subsequent victim, Sakina Abowath, told police about a blonde man (on the first responder report) which later transfigured into light brown hair, then just “brown”, then to Richard Ramirez’s near-black. It suggests a combination of media influence and potential police manipulation.

We’ve never seen Somkid Khovananth’s police statement, only a press release. For some reason it was never included in the appeal exhibits and it has left a critical information gap: how she described the suspect to the first detectives at the scene. Its omission could be seen as suspicious. Was there a reason it has been concealed and not released to the appeals team?

Recently, new details emerged from the March 1986 preliminary hearing transcripts. It transpired that Khovananth also changed her initial description. Then when defence attorney Daniel Hernandez cornered her in court – obviously in possession of her police statement – she suddenly couldn’t understand English and invented new meanings for words.

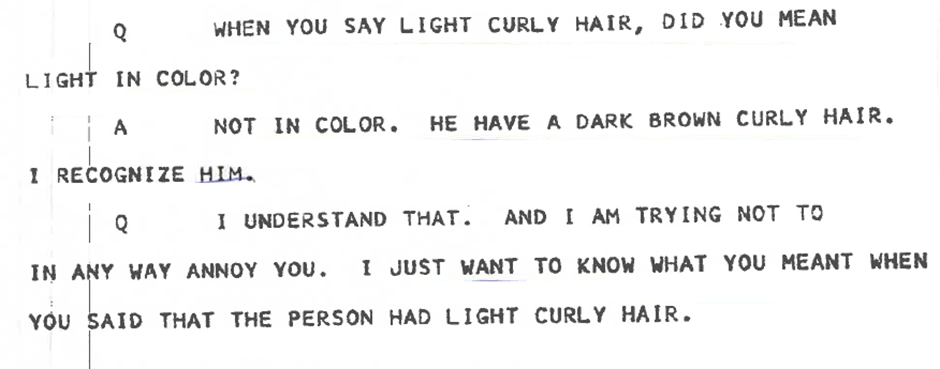

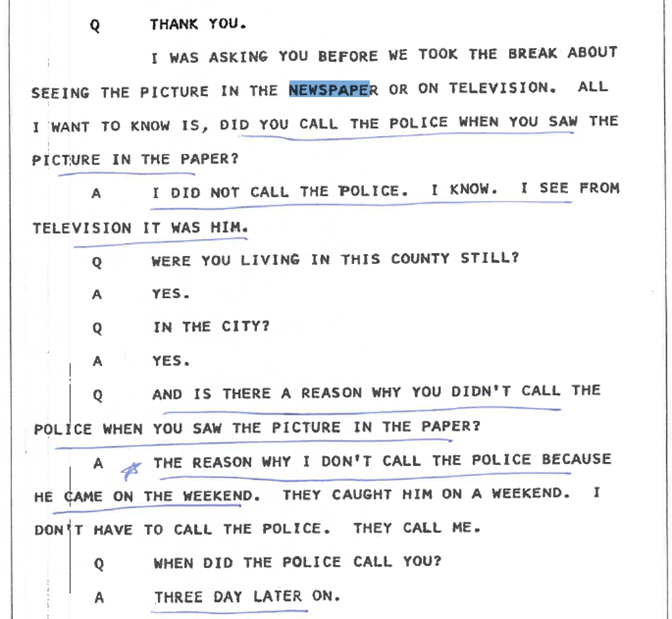

Here is some of the transcript. It was quite maddening to read. Somkid Khovananth had originally reported the suspect as having light brown hair, but she quickly backtracked and corrected herself to “dark brown.”

When asked to confirm that she told LAPD Sergeant Leroy Orozco that the suspect had light brown hair, Khovananth meanders off into the texture of the killer’s curls. She appears to be comparing the tight curls in her composite sketch to Richard Ramirez’s mugshot, with his loose curls. Now she claims that “light” is her word for “loose”.

HERNANDEZ: Did you describe this person as having brown curly hair?

KHOVANANTH: Yes. Light. Not dark brown.

HERNANDEZ: Light brown?

KHOVANANTH: No. Dark brown. Not light brown.

HERNANDEZ: Dark brown?

KHOVANANTH: Yes.

HERNANDEZ: Did you ever talk to Mr. Orozco here on my left about the description of this person?

KHOVANANTH: Yes.

HERNANDEZ: And did you tell him that the person you saw had light curly hair?

KHOVANANTH: Really, yes. It’s not curl- actually, that picture is not very look like really curly hair. He have very light curly hair.

Daniel Hernandez was unconvinced and pressed her to clarify. Instead, Khovananth’s answers became muddled before she abruptly insisted that she could identify Ramirez as the killer. Somehow, Judge Nelson considered that an adequate response.

HERNANDEZ: Can you tell me what you meant by light curly hair?

KHOVANANTH: He’s not really – that picture is really similar. The picture I can identify him.

Hernandez continued to press her, but she held firm, claiming she had always said the suspect’s hair was dark like Ramirez’s. And in case there was any doubt, she repeated that she recognised him – dodging the question entirely. Here, she is clearly becoming hostile.

HERNANDEZ: When you say light curly hair, did you mean light in colour?

KHOVANANTH: Not in colour. He have a dark brown curly hair. I recognize him.

HERNANDEZ: I understand that. And I am trying not to in any way annoy you. I just want to know what you meant when you said that the person had light curly hair.

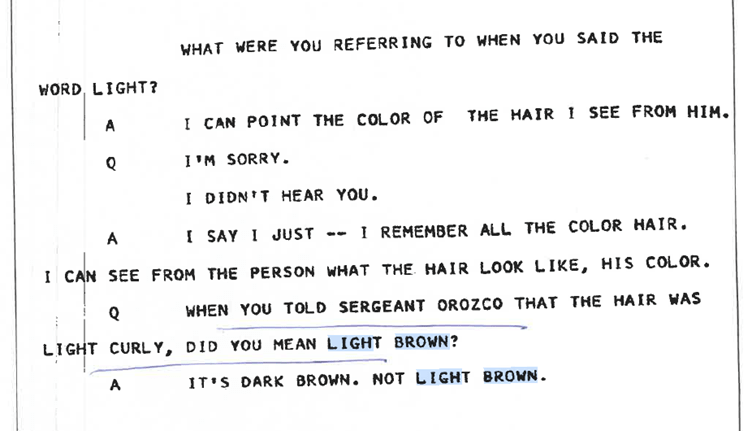

Daniel Hernandez was determined to get it out of her, but again Khovananth deflected, saying she could point to Richard Ramirez’s hair to show what colour it was. She knew she had described the suspect as having light brown hair in her statement, but now she was one step away from looking like a liar.

Her attempt to redefine “light” as “not very tight curls” is linguistically implausible – she clearly did once say “light brown hair,” and now she’s trying to retrofit that to match Ramirez’s darker appearance.

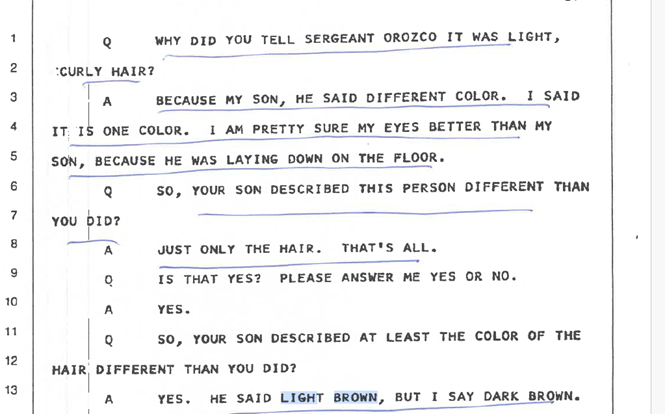

At this stage of the preliminary hearing, Ramirez’s defence team actually performed reasonably well. Daniel Hernandez did what a good defence lawyer should: he pinned Khovananth to her earlier description. Finally, she conceded that she had originally reported a light brown-haired suspect – but now offered a new excuse. It wasn’t her error, she said, but her son’s. Because he had been lying on the floor during the attack, he supposedly saw the colour differently, and she agreed to let the detective write it down that way.

HERNANDEZ: Why did you tell Sergeant Orozco it was light, curly hair?

KHOVANANTH: Because my son, he said different color. I said it is one color. I am pretty sure my eyes better than my son because he was laying down on the floor.

HERNANDEZ: So your son described this person different than you did?

KHOVANANTH: Just only the hair. That’s all … He said light brown. But I say dark brown.

It seems implausible that a mother would allow her eight-year-old son to dictate the final eyewitness description on a police statement – especially when she had spent far more time face-to-face with the attacker. Her later claim about her son’s conflicting memory (“he said light brown, but I say dark brown”) actually reinforces that at least one of them – and most likely both – originally said “light brown.”

In terms of witness reliability, that represents retroactive contamination. The first description given is generally the most trustworthy, as it precedes any external influence such as media exposure or police suggestion. At the time of the Khovananth attack (20 July 1985), there was little public awareness of a “Night Stalker” – the crime was reported simply as a robbery gone wrong. Yet Khovananth later denied that her recollection had been influenced at all.

The Newspaper Lie

Daniel Hernandez sought to establish how much exposure Khovananth had to the media before identifying Ramirez. By late August 1985, newspaper and television coverage of the Night Stalker was in overdrive. Ramirez’s mugshot aired on TV the night of August 30 and appeared in the papers the following morning.

HERNANDEZ: All I want to know is, did you call the police when you saw the picture in the paper?

KHOVANANTH: I did not call the police. I know. I see from television it was him.

HERNANDEZ: And is there a reason why you didn’t call the police when you saw the picture in the paper?

KHOVANANTH: The reason why I don’t call the police because … they caught him on the weekend.

Khovananth’s reply is simply that she recognised Ramirez on TV but didn’t tell police because it was the weekend. It’s an illogical excuse – mere recognition of her husband’s murderer should have prompted urgency. Her admission that detectives phoned her three days later only reinforces that she made no effort to contact them once the weekend had passed. She then shifts the blame, claiming it was the police’s duty to call her – an excuse echoed by other witnesses who also failed to contact detectives. It suggests they were coached to justify their silence should this question arise.

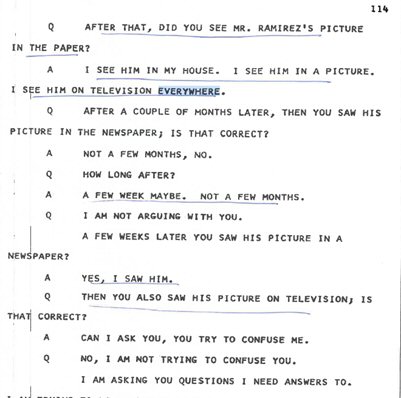

Next, Hernandez asked whether she saw Ramirez’s mugshot in the newspaper before or after his arrest. Khovananth grew confused over whether he meant the composite sketch or the real photograph. She said she remembered seeing both – first the sketch in early August, then Ramirez’s real face after the 30th. But when Hernandez asked her to confirm that she had followed newspaper coverage, she suddenly claimed she couldn’t tell the difference between drawings and photos, asking him to repeat questions as if she no longer understood English.

When Hernandez moved to specific dates, she said it was too long ago to remember. Yet if she cannot recall that, how can her memory of the attacker – from even earlier – be considered reliable?

The contradictions continued. When asked whether she kept up with the Night Stalker story, Khovananth admitted, “I follow the newspaper because I wanted to know if they caught him.” But only a few questions later, she insisted she didn’t read newspapers at all – she only watched television.

KHOVANANTH: I just only see it on television. I don’t read newspaper. At that time I was upset. Who can read anything?

HERNANDEZ: So, you didn’t read the newspaper?

KHOVANANTH: No. I know him. I don’t have to read the newspaper.

Realising she was tripping over her own lies, Khovananth returned to her rehearsed script – that she knew and recognised Ramirez as the killer – before retreating again behind her claim of not understanding English.

HERNANDEZ: When did you become aware that this person that had been in your house was called the Night Stalker?

KHOVANANTH: Can you repeat that question?

HERNANDEZ: When did you become aware yourself that the person in your house was being called the Night Stalker?

KHOVANANTH: I don’t understand your question.

Hernandez asked for a translator, but Judge Nelson denied the request. That refusal ensured her contradictions went untested, allowing her to hide behind confusion and waste time with repeated ‘I don’t understand’ answers.

Further Media Exposure

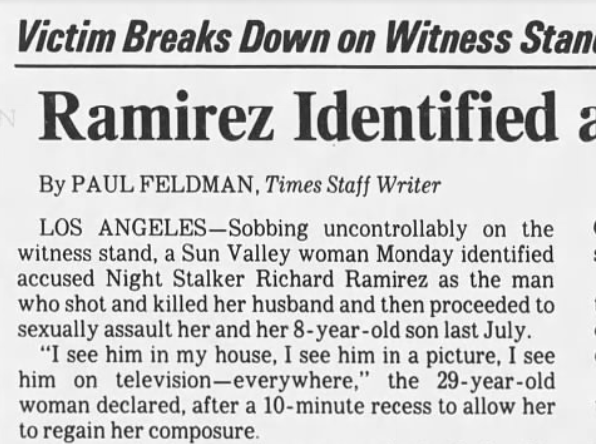

The newspapers reported that she screamed, “I saw him in my house. I saw him in a picture. I saw him on television everywhere!” and described her as sobbing uncontrollably. There had to be recesses so she could collect herself. Yet none of them wrote about her contradictions or lies. Multiple times in this section of the transcript, Khovananth accused Hernandez of trying to confuse her.

Khovananth conflates three separate timeframes and sources – the intruder she saw that night, the composite drawing, and Ramirez’s televised arrest and mugshots. It reads as someone trying to maintain certainty (“I know it’s him”) while avoiding precise timelines that might unravel her identification.

This circular pattern suggests she’s anchoring her memory to media exposure rather than the actual night of the attack. When she says “I see him in my house. I see him in the picture. I see him on television,” she’s blending experiences – a known eyewitness phenomenon called source confusion or memory integration. In short, she’s re-remembering the man through the lens of Ramirez’s media image, which is exactly what Daniel Hernandez was pressing her to admit. When caught, she lied to preserve that illusion of certainty.

Emotional Control

There’s also a degree of emotional control at play. Each time, Khovananth reverted to the lines she rehearsed with Philip Halpin: that she saw Richard Ramirez in her home and that he was the same man in the newspapers and on her television set. These were said in a dramatic and hysterical manner that won the sympathy of the press – who never mentioned the “light brown hair” statement. She also cried about remembering Ramirez’s “big eyeballs and rotten teeth” that played into the media image of the Night Stalker. This does not match others’ descriptions.

She attempts to flip roles and attempts to take control of the exchange: “Can I ask you? You try to confuse me” and “I told you I see this man in my house. He sit right there next to you.” She seizes emotional authority to neutralise or stop cross-examination. That’s often seen when a witness has been rehearsed or feels pressure to “perform” conviction.

Khovananth’s trauma was genuine; the attack was horrific, and trauma alone can distort memory. That much is undeniable. But her recollections are inconsistent, defensive, and at times theatrical. The sudden outbursts toward Ramirez appear scripted by Halpin, designed to sway the press (there is no jury in a hearing).

When cornered, she shifted into a victim-authority role instead of giving a direct, credible response – something as simple as, “Yes, I saw him on TV and in the papers, but I recognised him instantly from his features.” Such an answer would have addressed the contamination issue. Instead, she spun in circles, avoiding any admission of media influence while simultaneously letting on that she had followed the case.

Her confusion, then, seems strategic rather than linguistic. Her English was broken but functional; she had lived in the U.S. for a decade. She had no difficulty under direct examination by Philip Halpin, and she clearly understood Hernandez’s questions and recognised when he was cornering her. When that happened, she used shields: “You try to confuse me” or “I cannot answer your question.” This reads as a defensive mechanism – protecting not her trauma, but the contradictions between her original statement and the prosecutor’s coaching. It’s likely Halpin warned her that the defence would “try to trick her,” priming her to interpret every challenge as manipulation.

Shoes

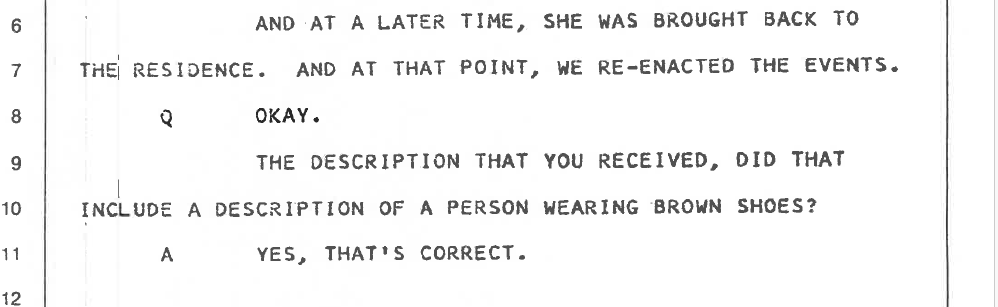

One last thing: without going into the Avia shoes saga, it is important to note that the alleged sneakers were an uncommon size 11.5 black Avia Aerobics 445B models. This was based on an unproven theory that the killer was clad in black. However, Khovananth never said he wore black. He had brown pants, a blue shirt with either multicoloured patterns or stripes on. And according to the statement Daniel Hernandez had, brown shoes.

Khovananth described them as “very heavy”, “leather”, “army shoes” and that they were black. She told Daniel that she told police the shoes were black.

However LAPD Detective Brizzolara, who took the statement, later testified that she did indeed say brown shoes.

Here, a pattern emerges with other incidents. Sakina Abowath said that her attacker wore heavy lace-up boots that he removed before the rape. This also matches with Inez Erickson allegedly telling a neighbour that the intruder wore “combat boots.” But Night Stalker Task Force members claimed that Kinney Stadia sneaker prints were found in the Abowath’s house, never boot prints. Perhaps all three witnesses were confused and mistaken. But this looks like an interesting connection. Since we know that the Avias weren’t really rare – and there’s no way of knowing what colour shoes left the prints – we must allow for the possibility that the prints ended up there another way: from a visitor, a prowler or a guest.

Leave a comment