By Venning

The story the public is familiar with: on 17th March 1985, Richard Ramirez entered the garage of 22-year old Maria Hernandez and shot her. He proceeded into the condominium and shot Maria’s housemate, 34-year-old Dayle Okazaki, in the head. Ramirez departed without taking anything but left his hat behind, and for reasons unknown, spared Hernandez when he realised that she had survived. He left in a hurry to murder Tsai-Lian Yu, nearly four miles away. But there might be more to the story.

The Attack

On the night of March 17, 1985, Maria Hernandez returned home via the garage at the rear of the property, for which an automatic was triggered upon entry. Once inside, she pressed a button to close the garage door and headed for the internal door to the property. She heard an “undistinguishable” noise; later attributed (by Detective Gil Carrillo) to the sound of her attacker slamming his hand on one of the cars to attract her attention.

Twenty feet away stood a man, who pointed a “blue steel” gun at her face, held with both hands at his shoulder height. He advanced upon her and fired. She reflexively raised her hand to shield her face, as the automatic light went out and the bullet ricocheted off her keys. The force of the shot sent her falling to the floor. The shooter walked past her into the house, pushing her body aside with the door as he did so.

Hernandez staggered out through the garage door and tripped over, at which point she heard another gunshot. Still bleeding from her hand, she ran down an alley next to the property and out onto the street, where she saw the attacker leaving via the front door. He spotted her and aimed the gun at her. She pleaded for him not to shoot her again; he obeyed, lowered the gun and walked off into the night. Hernandez re-entered the property to find Dayle Okazaki lying face down. She called 911.

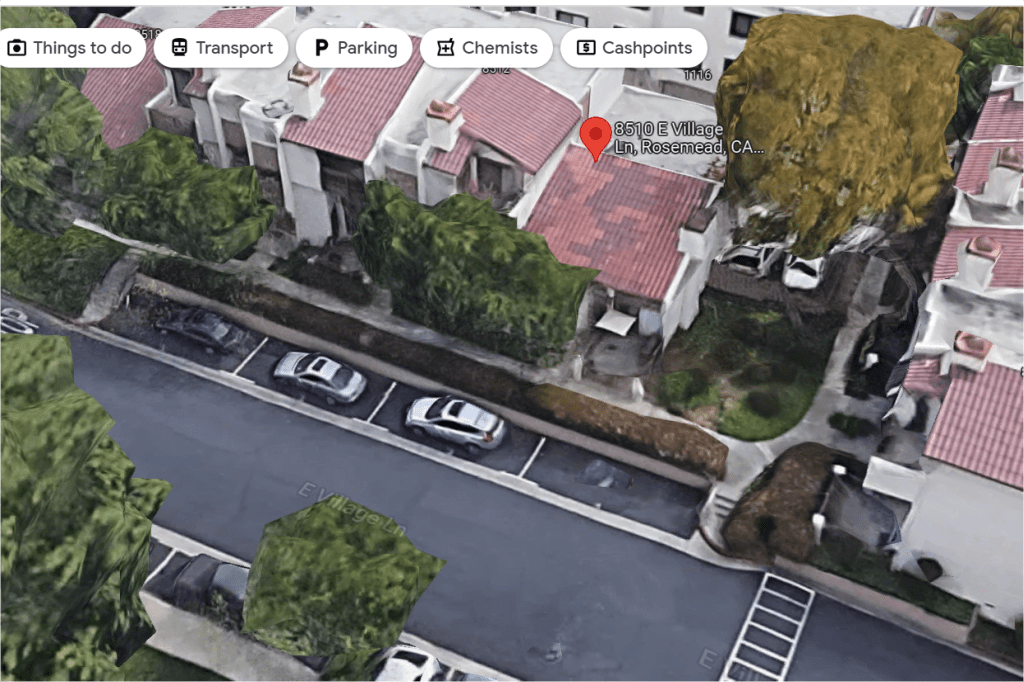

Below are Google Earth images of their condo, this is the front, where Hernandez saw the attacker exiting. She was walking west (towards the right of this image) and he was walking east (left in this image). Note that you cannot see any street lights.

Below is the rear of the property and the lane/alley that runs behind the houses.

Deputy Sheriff Powell arrived. The report in the petition says 10:54pm, but this is possibly a typing error or Maria misspoke at trial which was reflected by the transcripts – she testified that she returned at 11:30. Police documents are more likely to have the correct time, so presumably 10:54 is correct. An “unidentified witness” told Powell that the suspect was a white male. (Habeas Corpus pg. 47). The witness is never mentioned again and did not testify at the trial.

Detective Gil Carrillo arrived at 12:20am and noted that the garage light remained on for just 8 seconds. It was originally supposed that Maria Hernandez looked at the gunman for all eight seconds, but in recently unearthed court motions, it was revealed that she only saw him for two seconds.

Evidence at the scene

- An AC/DC baseball cap just inside the garage threshold.

- Fingerprints inside the property.

- A heavily distorted .22 bullet extracted from Dayle Okazaki’s skull.

The First ‘Night Stalker’ Witness Identification

At the hospital, Maria Hernandez told Detective Carrillo that the attacker was either a light-skinned Caucasian or Mexican male with brown eyes and a “very determined look on his face.” She estimated that he was between 5’9” and 6’1.

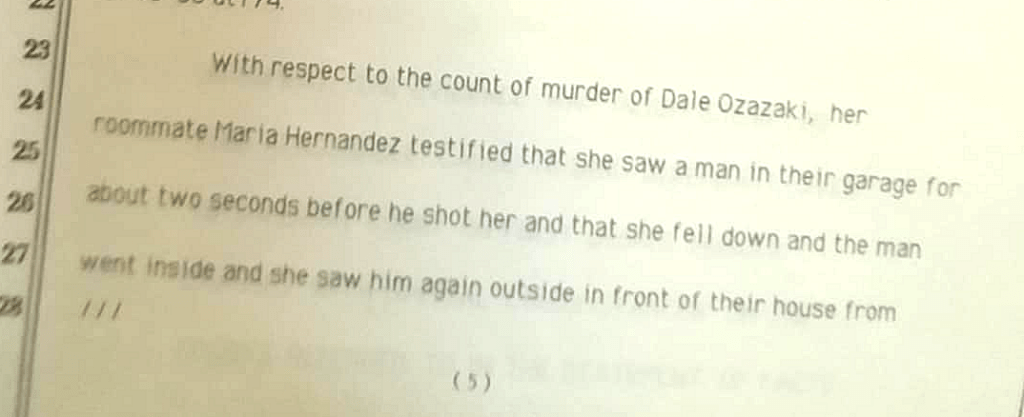

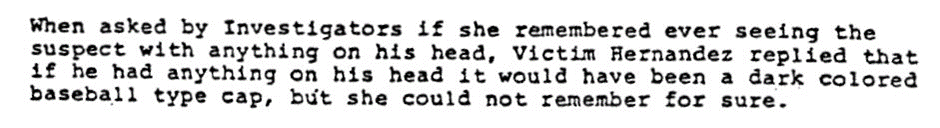

Hernandez stated that her assailant was wearing a black “Members Only” type jacket over a white shirt, but that she cannot remember whether the attacker was wearing a hat or not – but if he was, it was dark. Below, Hernandez’s April 15, 1985 police statement from Habeas Corpus Document 20-3.

It seems that Hernandez was asked a leading question because Carrillo had found an AC/DC hat. She did not remember the hat independently. If the gunman was wearing it, would she not have remembered its distinctive logo?

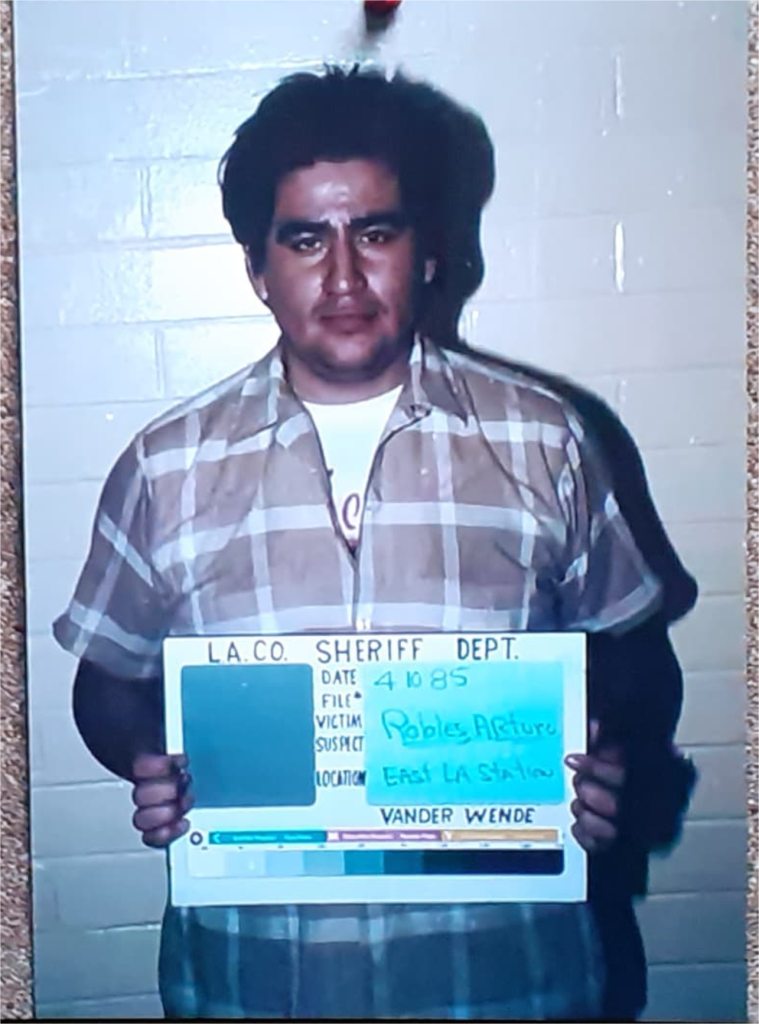

Maria Hernandez attended two line-ups in April and July 1985 and she was unable to identify any of the men as the murderer. Detective Carrillo showed her two photo spreads, each with six images of suspects, none of which was Richard Ramirez (who had not been arrested at this point). Maria chose one suspect from each of the spreads. In the 2021 documentary, Night Stalker: The Hunt for a Serial Killer, viewers were shown one of the suspects: Arturo Robles.

Arturo Robles was accused of stalking young women – Carrillo claims they were minors – and his house was raided. Police discovered he owned a Members Only jacket as well as swathes of pornographic images of women. Detective Carrillo claims there were torn women’s underwear too, but Robles denies this. Indeed, a copy of the search report shown on Netflix does not list them as items found, so there is no evidence for Robles’ underwear slashing hobby. Nevertheless, the police declared that Robles was “a freak, but not your freak” and Hernandez did not recognise him at the line-up. Our book discusses the Arturo Robles aspect in more detail.

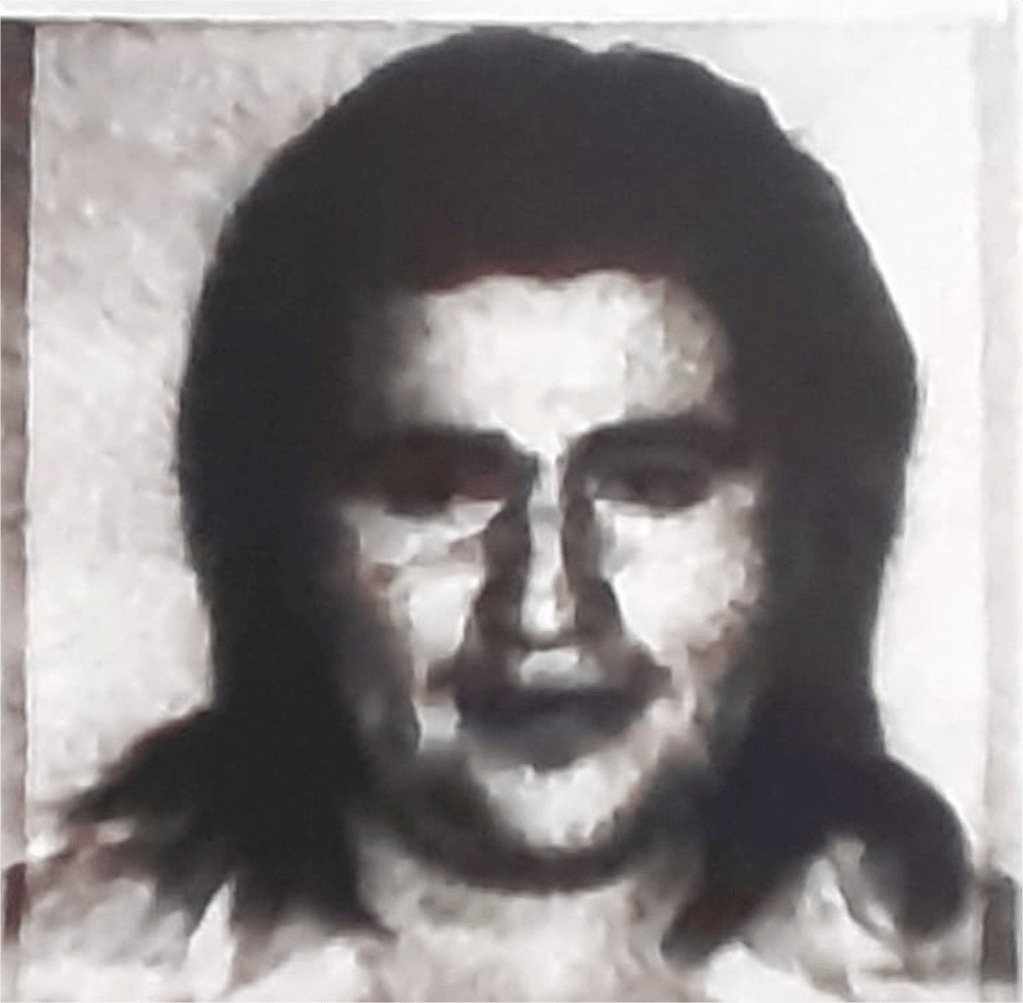

Maria Hernandez assisted Deputy Mahlon Coleman to create a drawing of the suspect below.

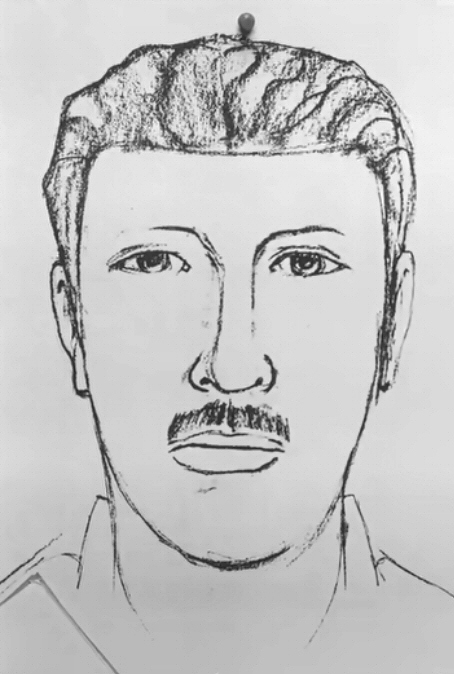

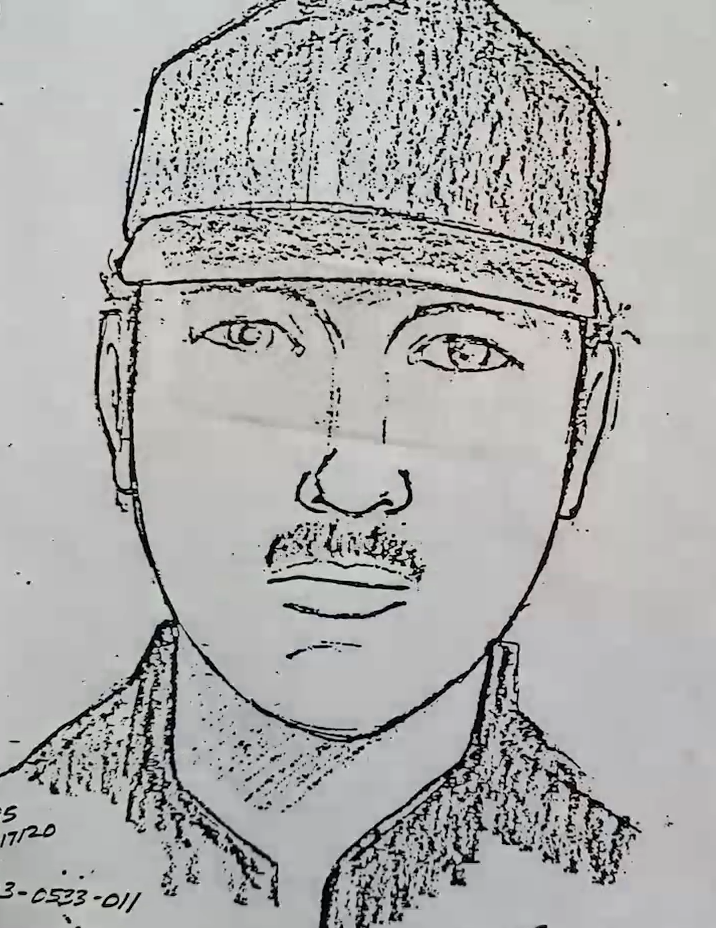

Later, a second sketch was released wearing a cap.

When Ramirez was named as the prime suspect, his face was shown on the news up to five times per day and was displayed on the front page of all the newspapers, complete with a description of him, spreading false information that all the survivors had described the killer this way.

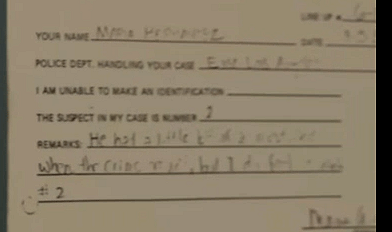

Hernandez attended a live line-up after Ramirez’s arrest. Ramirez was suspect Number Two, and she wrote “2” on her card. However, an officer was filmed holding up two fingers to encourage witnesses to pick Suspect Two. Below is video evidence.

A brief glimpse of Maria Hernandez’s line-up card can be seen on the Netflix documentary. While it is difficult to see, it states, “He had a little beard and moustache when the crime [illegible] but I do feel it was 2.”

Ramirez’s 2008 appeal revealed that Hernandez admitted to Detective Carrillo that she did not recognise Ramirez from his 1984 mugshot that was shown in the media.

“Hernandez told Carrillo after the September 5, 1985 live line-up that when she first saw Petitioner on the news he did not look like the suspect.”

– Habeas Corpus, pg. 128.

At the 1986 preliminary hearing, Maria Hernandez admitted that she saw the television reports and newspapers and discussed the case with friends and family, including on the day before Ramirez was arrested. She did not associate ‘Richard the Night Stalker’ with her own attacker. She did not recognise Ramirez as her attacker when she saw his mugshot.

However, at the trial, she claimed she could not remember saying this at the hearing.

“At trial, Maria Hernandez did not recall stating at the preliminary examination that Petitioner did not look like the composite drawing she helped to prepare. The picture of Petitioner that she first saw on television did not look familiar.”

– Federal Habeas Corpus petition 2008, pg. 49.

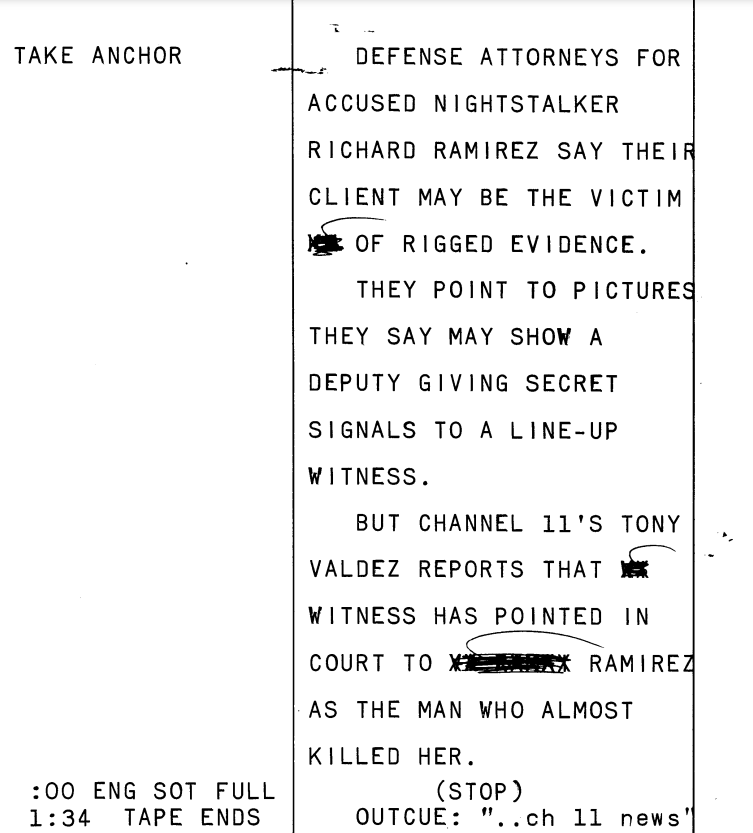

According to news report transcripts, Ramirez’s defence raised the evidence that the line-up was rigged with the officer signalling them to choose Ramirez, but this was dismissed because Hernandez had identified him.

At the pre-trial hearing in April 1987, Maria Hernandez identified Ramirez for the third time. However, she admitted she relied on seeing his face in person at the court, because she could not identify him from memory.

Ramirez’s defence attorneys failed to cross-examine Maria Hernandez for her weak witness identification, and the fact that she identified Ramirez regardless. They should have questioned how much the media had influenced her, her state of mind – shock distorts memory and perception. They should have highlighted the poor viewing conditions – she only saw him for two seconds in the garage and the second time she saw him it was outside in the dark.

In cases that involve witness identification, the defence should bring a psychologist as an expert witness, who will inform the jury of the factors that can negatively affect the victim’s perception and memory. They retained the estemed expert, Dr Elizabeth Loftus, but failed to brief her on the specifics of each case. The result was that the jury was bored – it was too academic and irrelevant.

“However, the defence failed to competently establish that Hernandez’s eyewitness testimony was unreliable. In closing argument trial counsel weakly observed: “Hernandez’s identification of Petitioner was of insufficient certainty to tie him to the crime.”

– Habeas Corpus, pg. 419.

Thus, Hernandez’s ID of Ramirez was inconsistent, influenced, and undermined by both her own doubts and police conduct.

Forensic Evidence at the Crime Scene

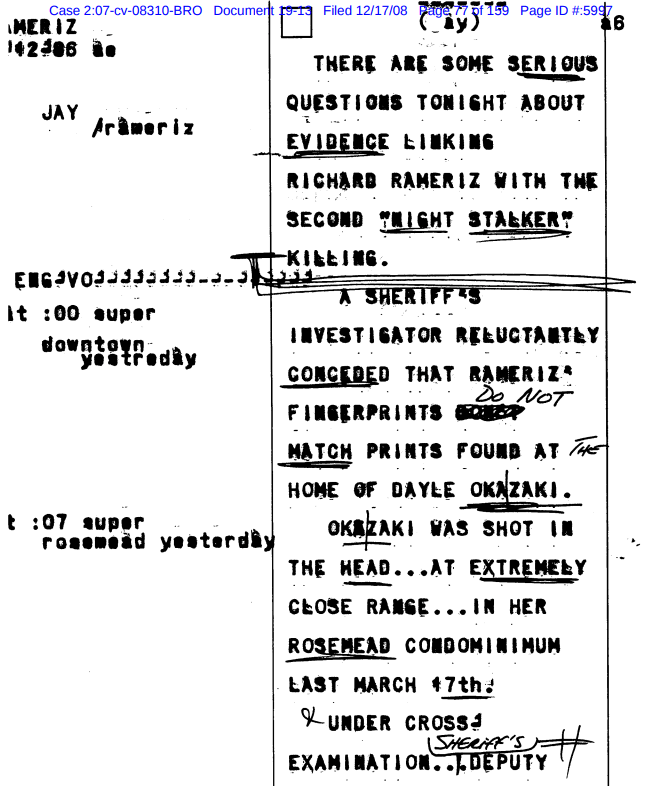

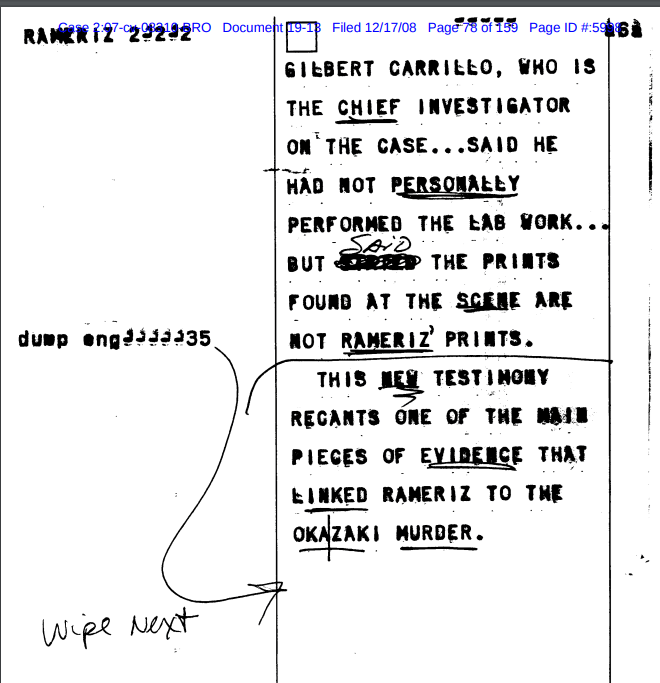

Fingerprints that did not belong to Ramirez were found at the scene. During the 1986 hearings, news report transcripts state that Detective Carrillo, while under cross-examination, “reluctantly conceded” that the prints were not his. From Document 19.13:

Note that in the second news transcript, it says “wipe next.” Could this be evidence that the news media was deliberately downplaying the fact that no evidence could conclusively tie Ramirez to that crime scene?

Firearms Evidence:

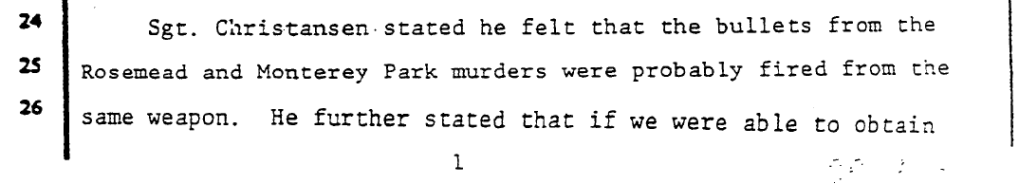

The prosecution presented weak ballistics evidence. In March 1985, the first firearms expert, Sergeant Robert Christansen, could not confirm that the same weapon was used in the Yu incident on the same night. This is because the bullets were between 60% and 75% mutilation.

By the time of Ramirez’s arrest, Christansen changed his mind but does not explain why. From the affdavit, Habeas Corpus Document 7.4:

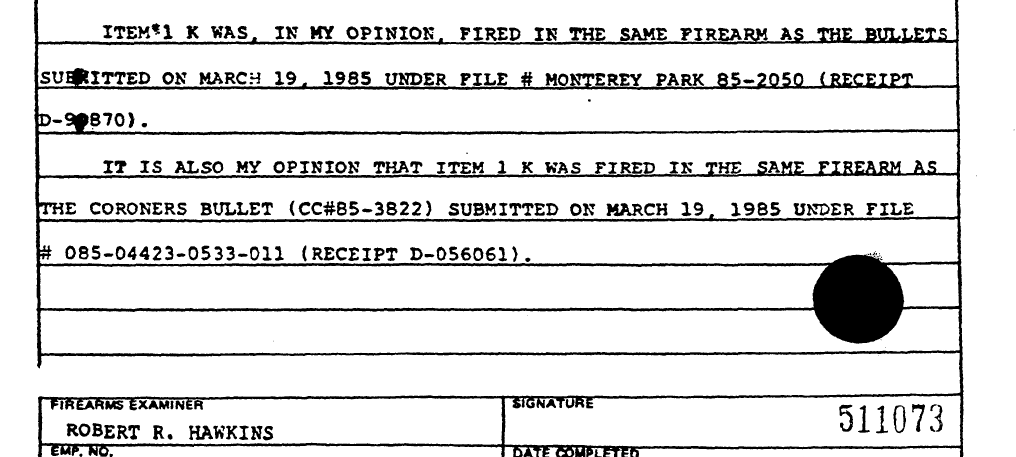

In August, a second firearms expert, Sergeant Robert Hawkins, concluded that not only did the Okazaki bullets match Yu, but also the Kneiding murders on 20th July. (Habeas Corpus document 7.20).

The problem was, Christansen and Hawkins listed different brands of revolver as the potential murder weapons. Furthermore, Christansen originally believed the Kneidings were killed with a .25 ACP pistol and not a .22 long rifle revolver, the assumed weapon in the Okazaki crime.

Ultimately, the prosecution used a different firearms examiner, Edward Robinson, who claimed – without demonstrating how – that Okazaki, Yu and the Kneidings were killed using the same .22 calibre revolver, supporting Hawkins over Christansen. However, the murder weapon was never recovered from any of these three crimes. This means it was impossible to accurately test fire bullets. How can they be too distorted to make meaningful comparison on minute and conclusive proof the next?

Ramirez’s defence managed to contact their own firearms expert, Paul Dougherty but neglected to communicate with him thereafter.

Worse, they conceded the prosecution’s evidence: “you have to assume their evidence is correct.” When contacted by Ramirez’s appeals team, Paul Dougherty’s verdict was that the ballistics needed retesting.

“In 1986, I was hired by attorney Daniel Hernandez to conduct examination of ballistics evidence in the Los Angeles case … However, my work was terminated because counsel failed to communicate with me I requested to be provide with the physical evidence, or that counsel made arrangements for me to view the evidence at the sheriff’s lab. As a result, I was unable to reach any conclusions or findings about the evidence.”

– Declaration of Paul Dougherty, Document 7.20.

The Hat:

The AC/DC cap found just inside the garage was thought to have fallen off the gunman’s head as he bent down to enter. Richard Ramirez was a fan of AC/DC and may have owned an AC/DC cap at some point – according to associates – but it was never established when they last saw him wearing it. Neither the defence nor prosecution had the hat tested for PGM markers in sweat. Brian Wraxhall, the defence’s special master, never received it in the evidence box in time for the trial.

The AC/DC link was sensationalised by the media who were under the grip of a moral panic related to Satanism – references to it were believed to be in rock music. However, Ramirez could not have been the only AC/DC fan in Los Angeles, and it must remain as circumstantial evidence – especially as the suspect did not even look like him. A month after Ramirez was arrested, a woman in Orange County was shot in her home by a man in an AC/DC cap.

Prosecutor Halpin and His Bad Faith Arguments

In a desperate attempt to connect Dayle Okazaki’s murder to other Night Stalker crimes, and to establish a modus operandi for the random and varied nature of the attacks, the prosecutor, Philip Halpin, argued that this was a burglary, despite nothing having been stolen. More accurately, Halpin claimed this was a failed burglary; that Ramirez had intended to burgle but was disrupted.

However, he neglected to establish the perpetrator’s intent or how he was disrupted; he obviously was not disrupted by Maria Hernandez arriving in the garage – he made no attempt to escape after being caught, shot her and left her for dead, before continuing upstairs to shoot her housemate. If the killer’s intent was burglary, he could have continued after murdering Dayle Okazaki, but he left immediately, carrying nothing but the murder weapon – Hernandez saw him.

The case against Richard Ramirez in the attack on Maria Hernandez and murder of Dayle Okazaki was built on shaky ground. Eyewitness identification was inconsistent and potentially influenced by media saturation and suggestive police tactics. Physical evidence, such as fingerprints and ballistics, failed to conclusively link Ramirez to the crime scene. Prosecutors made speculative claims about motive, while the defence failed to challenge flawed evidence and witness testimony with sufficient rigour. This was a grave miscarriage of justice.

1st Oct 2022

Leave a reply to Daisybubble74 Cancel reply